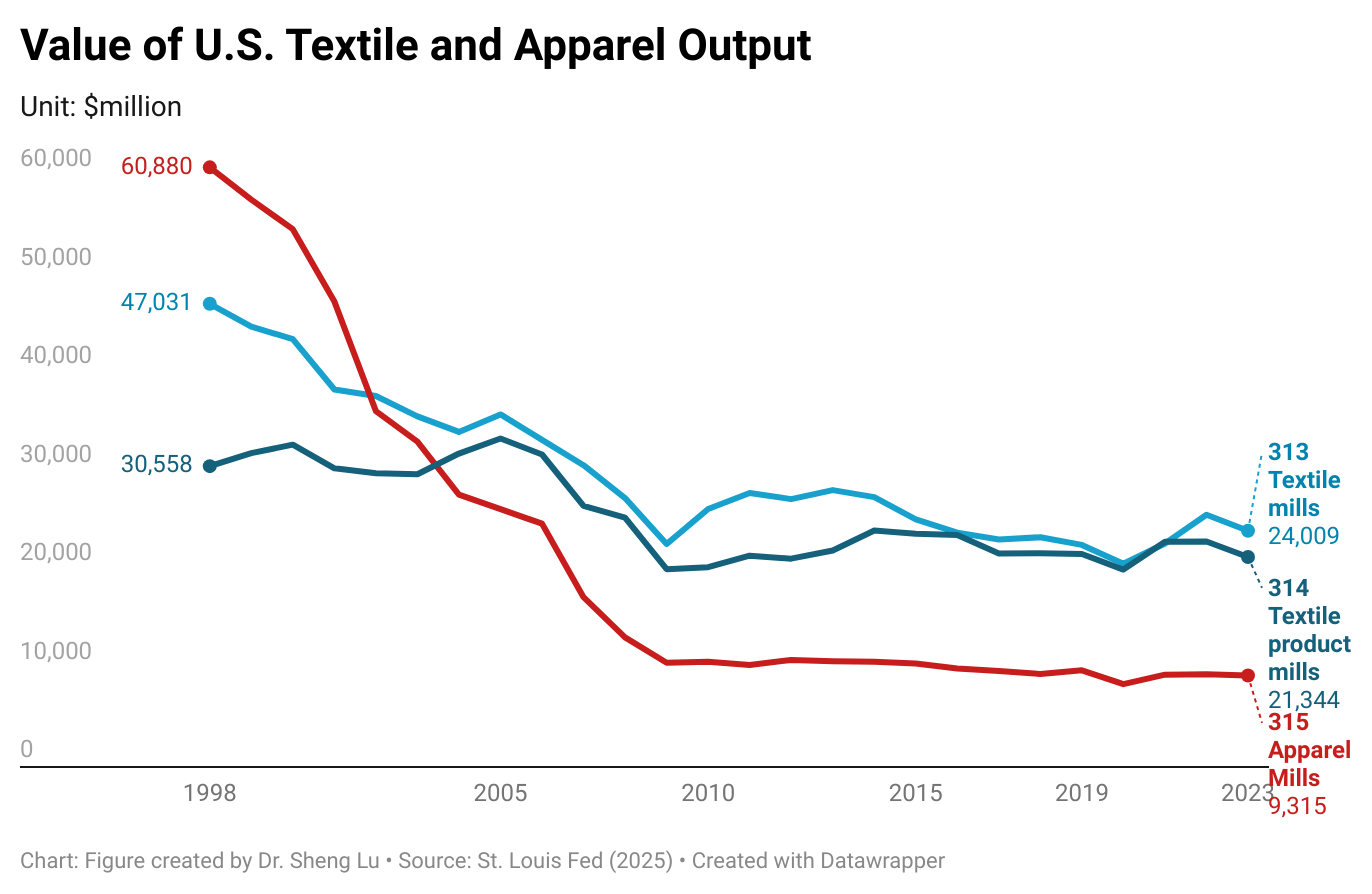

Textile and apparel manufacturing in the U.S. has significantly decreased over the past decades due to factors such as automation, import competition, and the changing U.S. comparative advantages for related products. However, thanks to companies’ ongoing restructuring strategies and their strategic use of globalization, the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector has stayed relatively stable in recent years. For example, the value of U.S. yarns and fabrics manufacturing (NAICS 313) totaled $24 billion in 2023 (the latest data available), up from $23.3 billion in 2018 (or up 2.8%). Over the same period, U.S. made-up textiles (NAICS 314) and apparel production (NAICS 315) moderately declined by only 1.8% and 1.6%.

More importantly, the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector is evolving. Several important trends are worth watching:

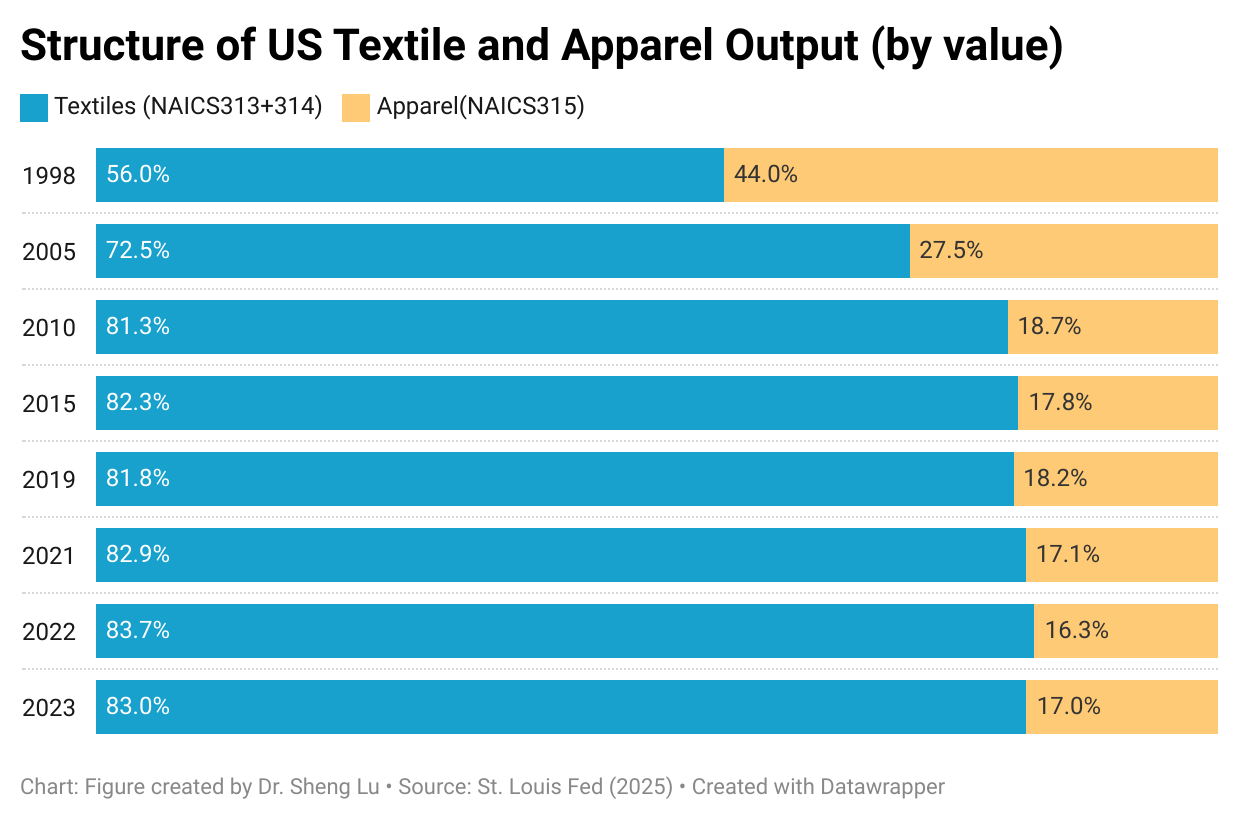

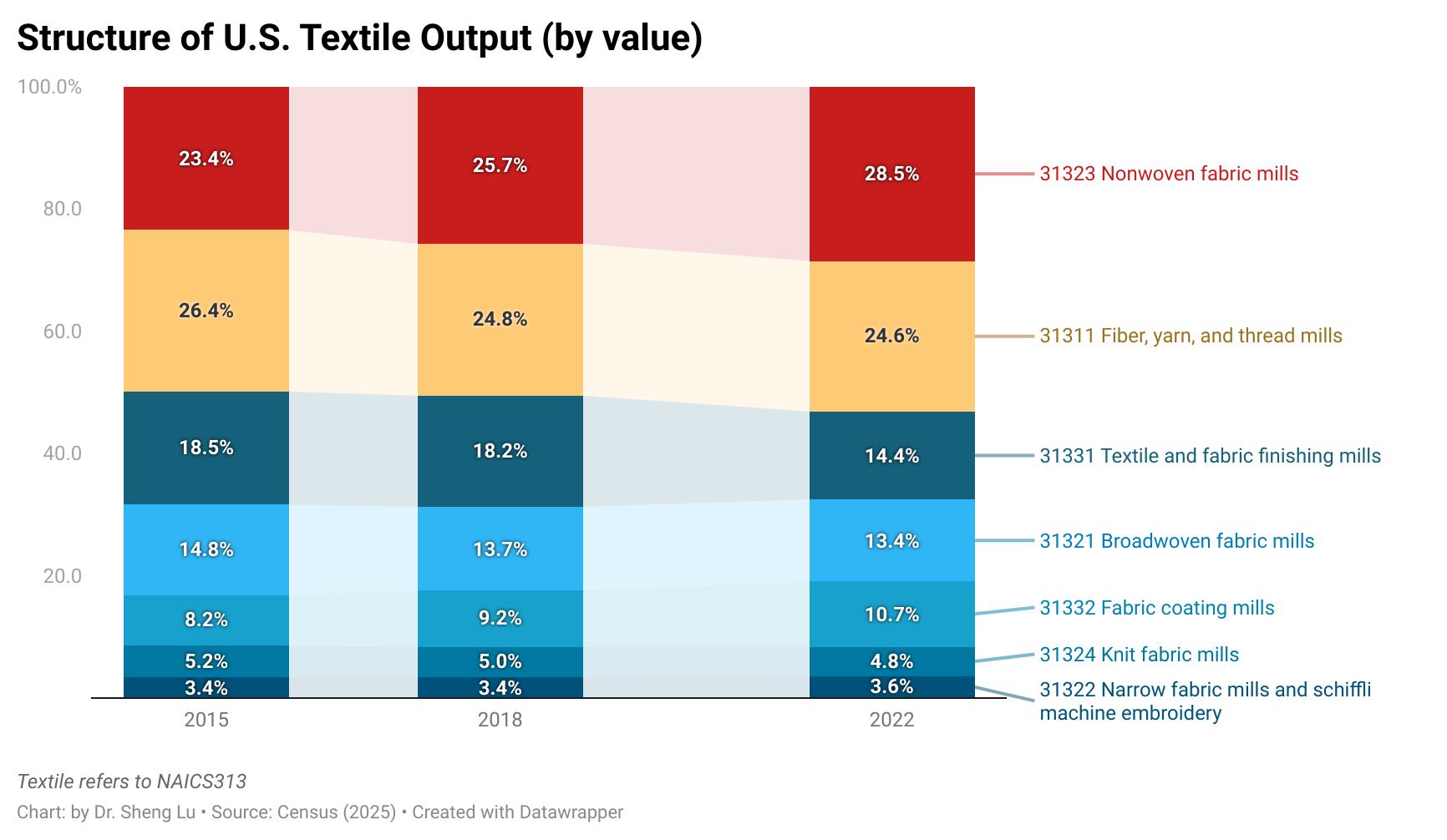

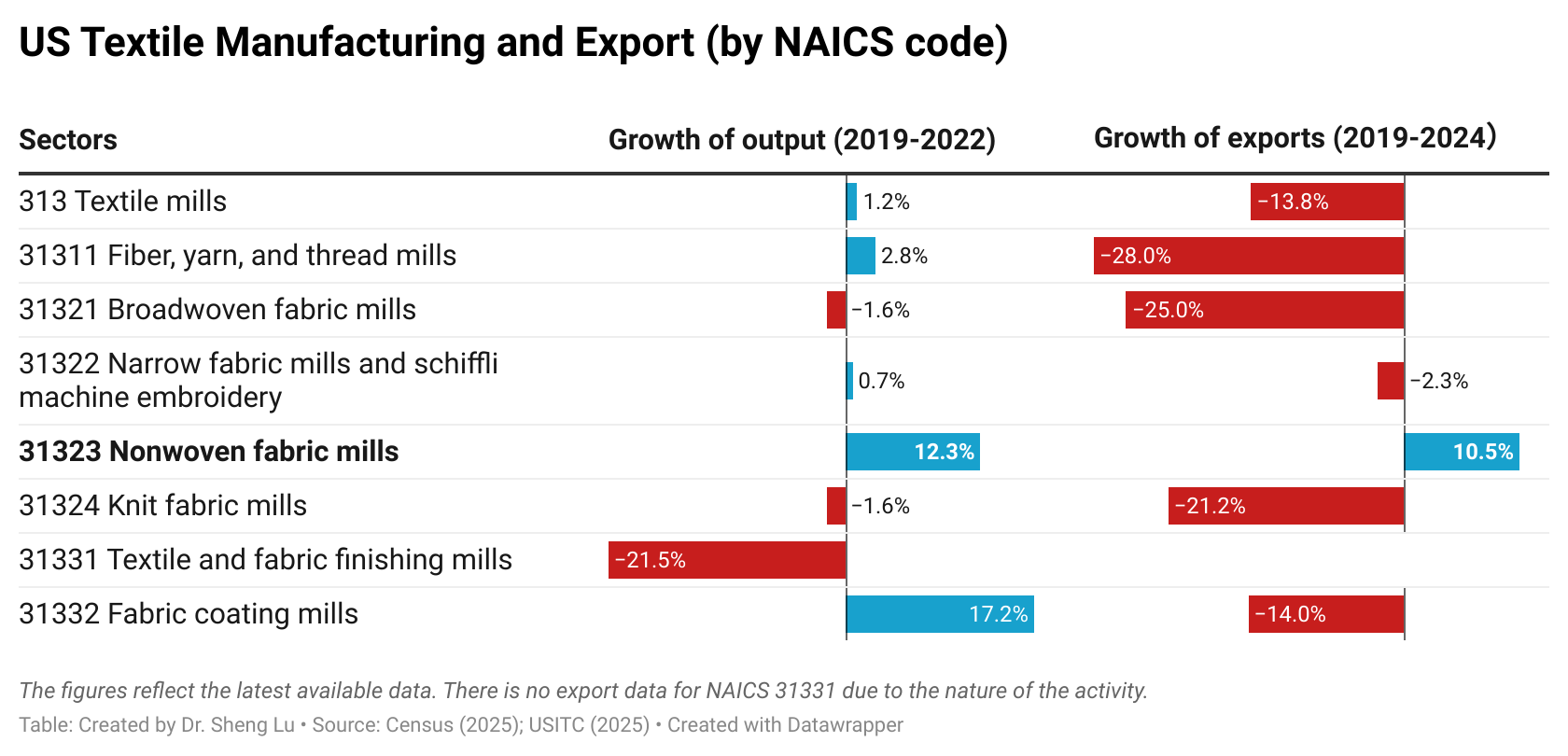

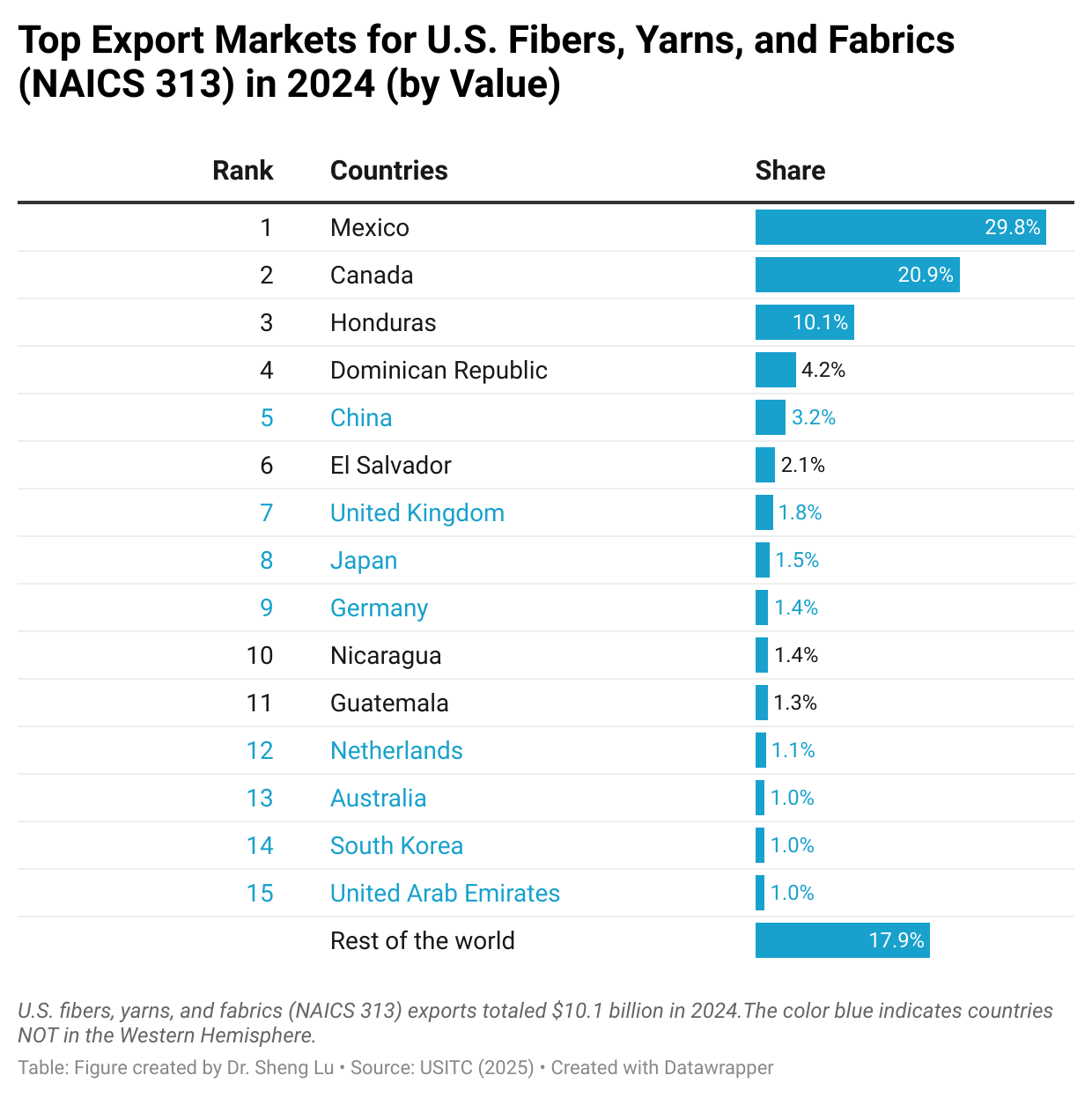

First, “Made in the USA” increasingly focuses on textile products, particularly high-tech industrial textiles that are not intended for apparel manufacturing purposes. Specifically, textile products (NAICS 313+314) accounted for over 83% of the total output of the U.S. textile and apparel industry as of 2023, much higher than only 56% in 1998 (U.S. Census, 2025). Textiles and apparel “Made in the USA” are growing particularly fast in some product categories that are high-tech driven, such as medical textiles, protective clothing, specialty and industrial fabrics, and non-woven. These products are also becoming the new growth engine of U.S. textile exports. Notably, between 2019 and 2022, the value of U.S. “nonwoven fabric” (NAICS 31323) production increased by 12.32%, much higher than the 1.15% average growth of the textile industry (NAICS 313). Similarly, while U.S. textile exports decreased by 13.75% between 2019 and 2024, “nonwoven fabric” exports surged by 10.48%--including nearly 40% that went to market outside the Western Hemisphere (U.S. International Trade Commission, 2025).

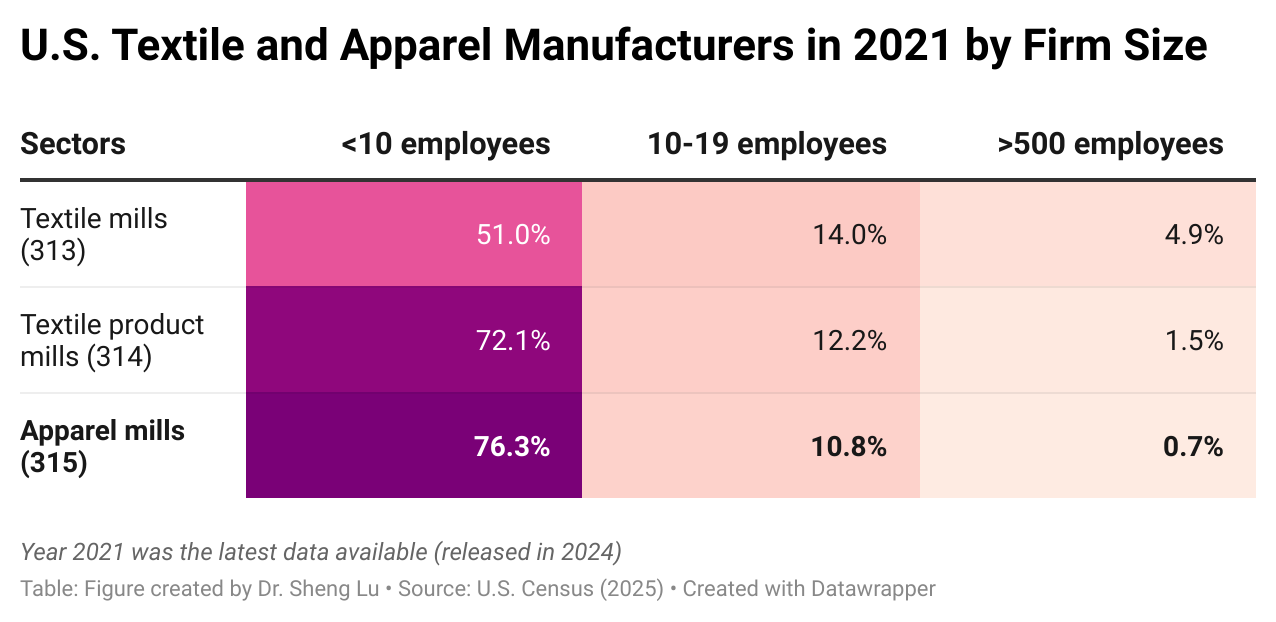

Second, U.S. apparel manufacturers today are primarily micro-factories, and they supplement but are not in a position to replace imports. As of 2021 (the latest data available), over 76% of U.S.-based apparel mills (NAICS 315) had fewer than 10 employees, while only 0.7% had more than 500 employees. In comparison, contracted garment factories of U.S. fashion companies in Asia, particularly in developing countries like Bangladesh, typically employ over 1,000 or even 5,000 workers.

Instead of making garments in large volumes, most U.S.-based apparel factories are used to produce samples or prototypes for brands and retailers. In other words, replacing global sourcing with domestic production is not a realistic option for U.S. fashion brands and retailers in the 21st-century global economy. Nor are U.S. fashion companies showing interest in shifting their business strategies from focusing on “designing + managing supply chain+ marketing” back to manufacturing.

Meanwhile, due to mergers and acquisitions (M&A) and to leverage economies of scale, approximately 5% of U.S. textile mills (NAICS313) had more than 500 employees as of 2021–this is a significant number, considering that textile manufacturing is a highly capital-intensive process.

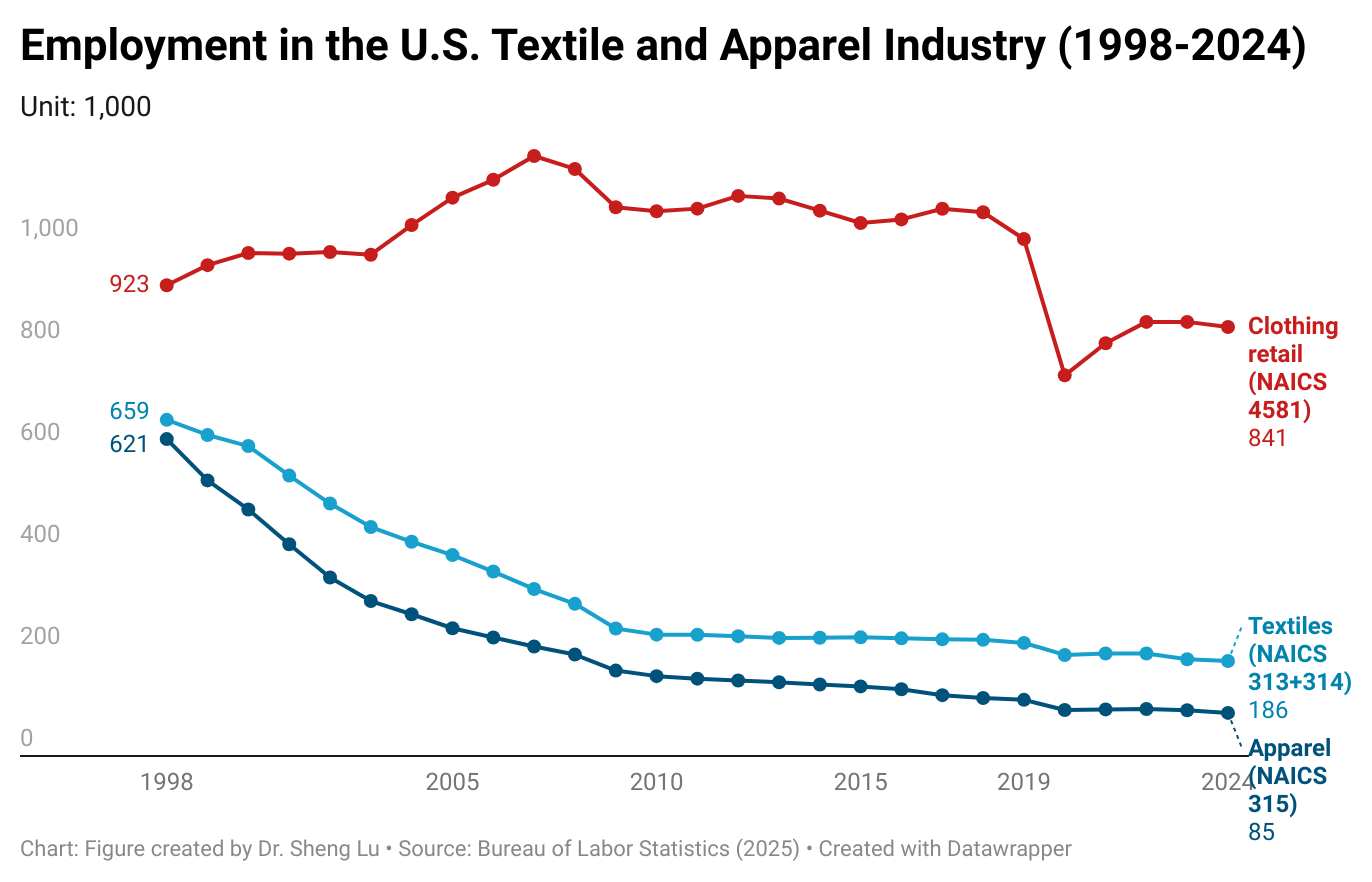

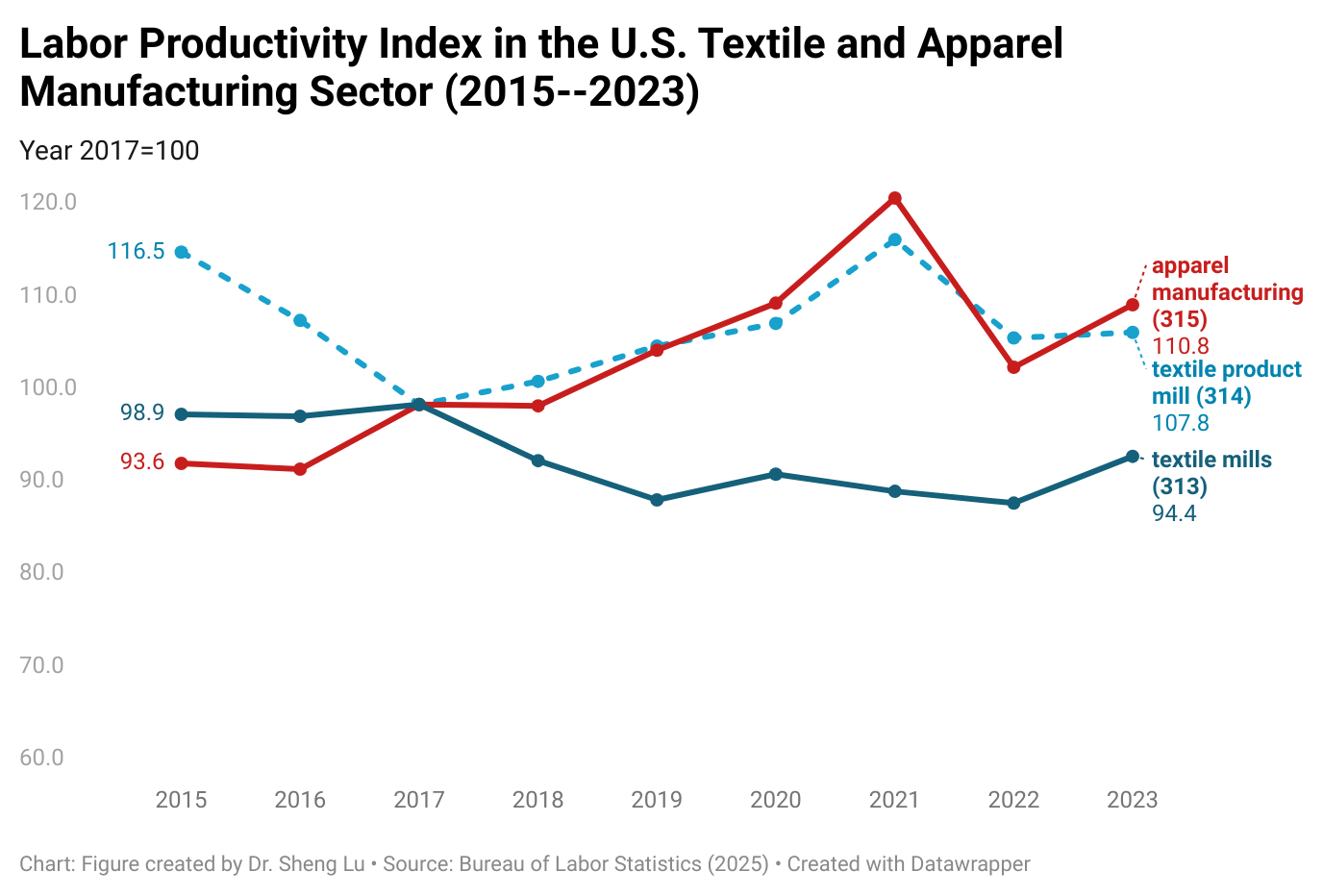

Third, employment in the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector continued to decline, with improved productivity and technology being critical drivers. As of 2024, employment in the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector (NAICS 313, 314, and 315) totaled 270,700, a decrease of 18.4% from 33,190 in 2019. Notably, U.S. textile and apparel workers had become more productive overall—the labor productivity index of U.S. textile mills (NAICS 313) increased from 89.7 in 2019 to 94.4 in 2023, and the index of U.S. apparel mills (NAICS 315) increased from 105.8 to 110.78 over the same period.

On the other hand, clothing retailers (NAICS 4481) accounted for over 75.7% of employment in the U.S. textile and apparel sector in 2024.

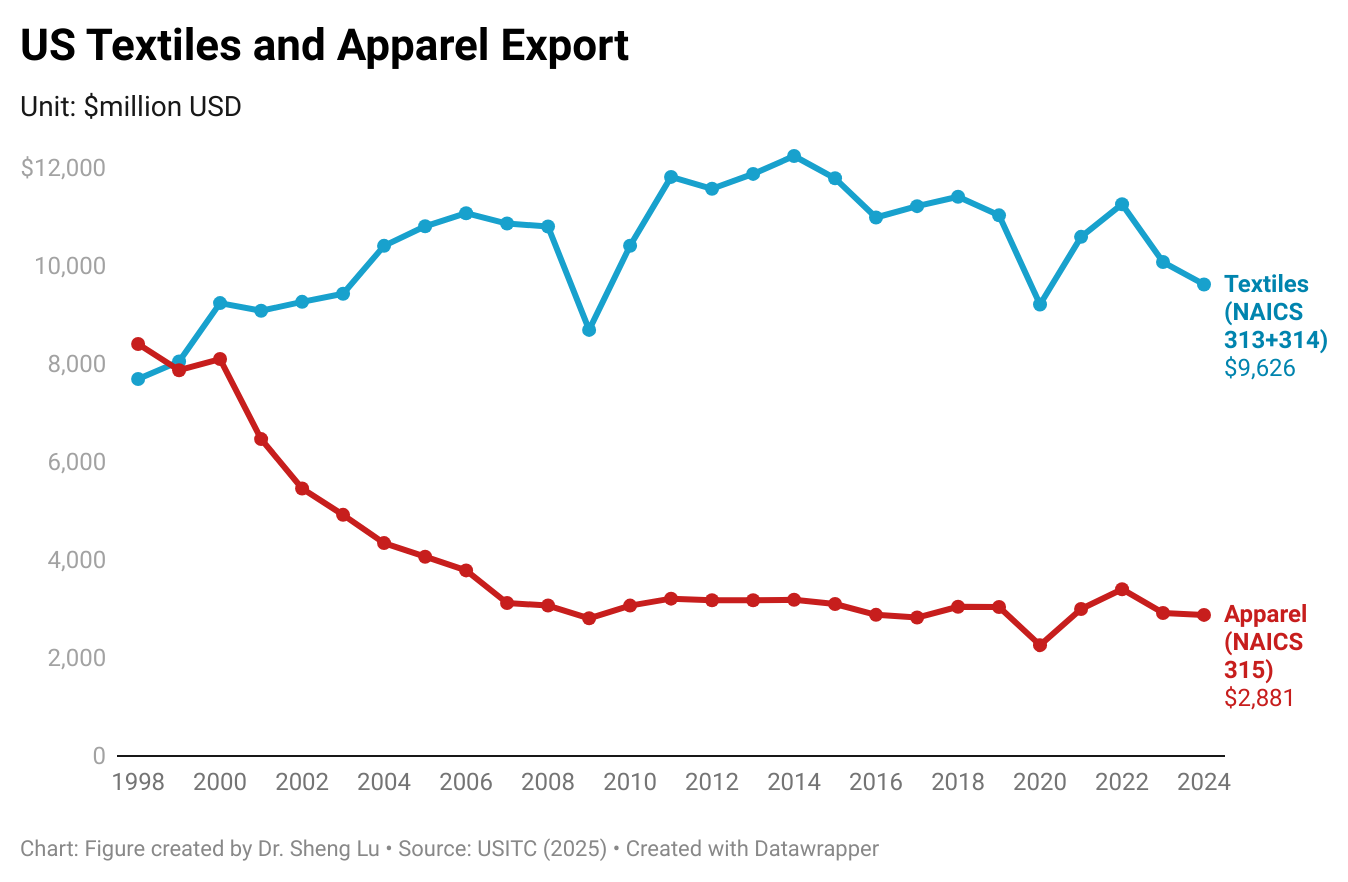

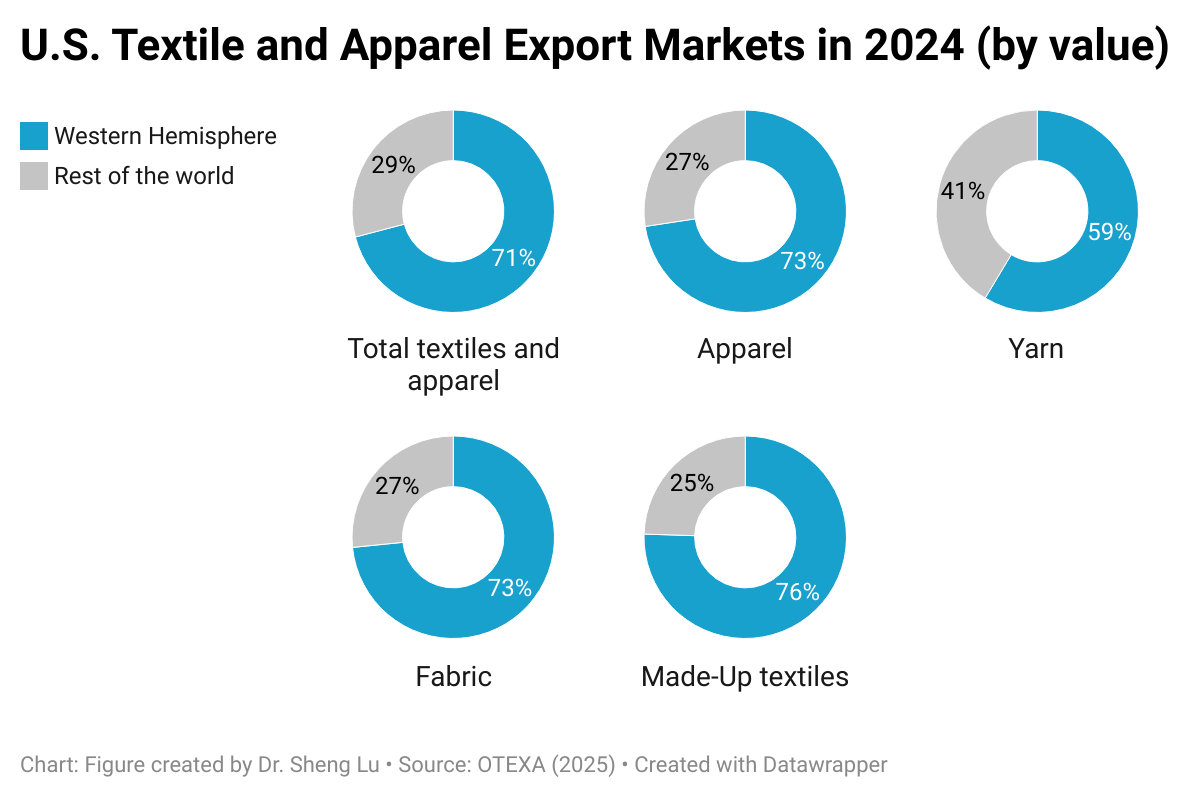

Fourth, international trade, BOTH import and export, supports textiles and apparel “Made in the USA.” On the one hand, U.S. textile and apparel exports exceeded $12.5 billion in 2024, accounting for more than 30% of domestic production as of 2023 (NAICS 313, 314 and 315). Thanks to regional free trade agreements, particularly the U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA) and the Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), the Western Hemisphere stably accounted for over 70% of U.S. textile and apparel exports over the past decades. However, for specific products such as industrial textiles, markets in the rest of the world, especially Asia and Europe, also become increasingly important. Thus, lowering trade barriers for U.S. products in strategically significant export markets serves the interest of the U.S. textile and apparel industry.

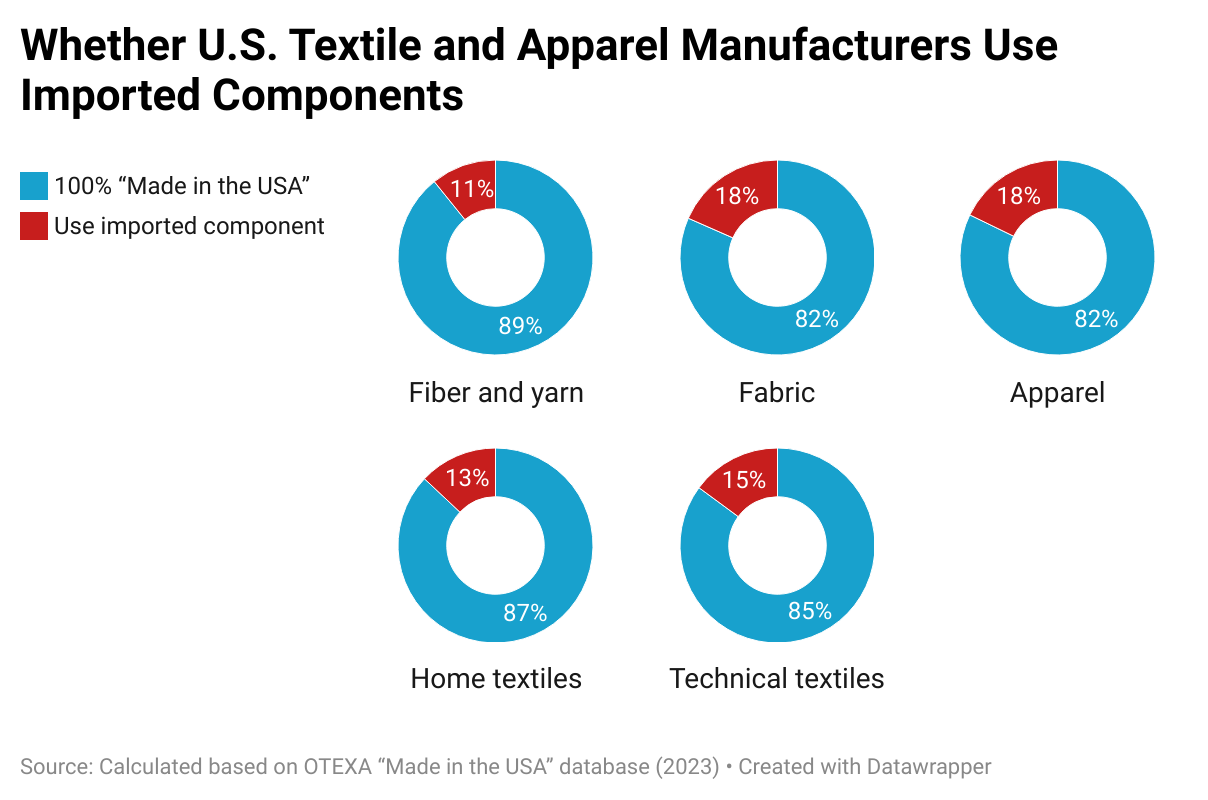

On the other hand, imports support textiles and apparel “Made in the USA” as well. A 2023 study found that among the manufacturers in the “Made in the USA” database managed by the U.S. Department of Commerce Office of Textile and Apparel, nearly 20% of apparel and fabric mills explicitly say they utilized imported components. Partially, smaller U.S. textile and apparel manufacturers appear to be more likely to use imported components–whereas 20% of manufacturers with less than 50 employees used imported input, only 10.2% of those with 50-499 employees and 7.7% with 500 or more employees did so. The results indicate the necessity of supporting small and medium-sized (SME) U.S. textile and apparel manufacturers to more easily access their needed textile materials by lowering trade barriers like tariffs.

By Sheng Lu

This analysis shows that U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing is increasingly producing more high-tech, specialty textiles like medical fabrics and protective gear rather than focusing on making large volumes of basic clothing. These products rely heavily on innovation rather than cheap labor. Also, most U.S. apparel factories are small and very adaptable, especially when they can access imported components. If we better supported small textile businesses by lowering trade barriers and offering tech support it could spark more domestic innovation. This approach could help them be more competitive globally. We could possibly be moving toward a new model where design and innovation happens in the U.S. while large-scale production stays global. This means that companies should be thinking about how to support the industry by building more balanced supply chains, not just trying to bring everything back home.

Hi Rian, I really liked your perspective especially how you pointed out that innovation, not just labor, is driving the future of U.S. textile manufacturing. I agree that supporting small businesses through lower trade barriers and better tech access could really help them compete. The idea of balancing global production with domestic innovation makes a lot of sense, and it’s probably the most realistic path forward for the industry.

The current state of U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing we see a sector that has evolved over time. While traditional large scale apparel production has largely shifted overseas, the U.S. textile industry has found strength in specialized, high tech, and non apparel textile products. These segments are growing and are increasingly driving U.S. exports beyond the Western Hemisphere. However, apparel manufacturing remains limited and highly fragmented, with most factories operating on a smaller scale, often producing samples not the mass market clothing. This reinforces that domestic production will not replace global sourcing. It can play a complementary role in doing this. With the decline in employment rate, labor productivity in the U.S. textile and apparel sector has improved due to technological advancements and capital intensive processes. International trade continues to be essential. Many smaller U.S. manufacturers rely on imported materials, we see the need for policies that reduce trade barriers to support small and medium enterprises. Overall, the U.S. textile and apparel industry is becoming more innovation driven than anything else before.

You summarized the key findings, but what are your thoughts on the revealed patterns? For example, What factors have been most important in shaping them? What patterns could continue to evolve or change? What could be the impacts of these changes?

This article is interesting because it points out how the United States textile and apparel manufacturing industry has changed over the years. In the United States trade and imports are a big discussion. There is a lot of talk about how trade hurts American jobs. But, when reading this article it becomes clear that trade is necessary and part of growth for business. Apparel factories in the United States today are micro-factories and mainly make small amounts of garments. Most mills have less than 10 employees meaning that sourcing apparel from the United States is not truly possible. This is interesting to read because in the current world many tariffs are being placed on imports such as garments which hurts the American apparel industry. Apparel retailers as stated by the article account for 75.7% of textile and apparel jobs in the United States. By applying tariffs on apparel these jobs are put at risk due to inability to import apparel people can afford. The United States is not an option for apparel production so, placing such high tariffs on items we cannot create makes it difficult for other areas of the industry to function. Something positive in the article is that non-woven textiles from the United States have increased. Perhaps it would make more sense given this information to place tariffs on textiles that the United States is able to produce themselves such as non-woven textiles in order to increase production than to place tariffs on items the United States cannot make in large quantities.

One concept from class that really connects to this post is when we learned about the production process of the garment industry. The first video we ever watched in class explained how different stages of production, like design, textile manufacturing, assembly, and retail, are spread across multiple countries based on cost and efficiency. Instead of one country doing everything, production is fragmented globally to maximize competitiveness.

This article clearly shows how the U.S. fits into that global value chain today. The U.S. specializes more in high-tech textiles, like nonwoven and industrial fabrics, while large-scale apparel assembly happens overseas. Since over 75% of textile and apparel jobs in the U.S. are actually in retail, imports play a major role in sustaining domestic employment. Tariffs on apparel don’t just affect foreign factories, but they directly impact U.S. retailers, consumers, and supply chain workers. Because most U.S. apparel factories are micro-factories focused on sampling, replacing imports with domestic production is not realistic in the current structure of the industry.

I also think your point about non-woven textiles is important. If the U.S. has a competitive edge in advanced textile production, policy should focus on strengthening those sectors through innovation incentives and strategic trade agreements, rather than imposing broad tariffs that disrupt the entire value chain.

This article’s discussion of the U.S. textile industry provided statistical context and information on how the current domestic manufacturing operates and on how tariffs will impact that. The mercantilist idea of bringing production back to the states that drove these tariff policies is ultimately unfeasible without high investment into the sector due to the lack of infrastructure and employees. In more than half of all textile, textile product, and apparel mills there are less than 10 employees, not nearly enough to provide all textile related products to a country of over 340 million people. The U.S. should instead focus its efforts on its absolute advantage in high tech driven “non-woven” fabrics which have increased production by 12.32%.

Overall, this blog post highlighted that although the US does not makes clothing as it used to, technology and industrialization have advanced to produce medical fabrcs and protective clothing. Therefore, in today’s industry, the “Made in the USA” label is mainly technical textiles. With most US apparel operations being on a smaller level, it hihglights that the United States still relies on imports and returning at the US’s old manufacturing rate currently is not plausible. The technical textiles that are produced in the United States is a prime example of the flying goose method and the future of other well-industrialized countries such as China after they move the majority of their operations elsewhere.

This article helped me understand how the U.S. textile and apparel industry is changing and becoming more focused on high-tech and non-apparel products like medical or protective textiles. I didn’t realize how small most U.S. apparel factories are, and it makes sense why they can’t replace global production. I also found it interesting that even with fewer workers, productivity is going up thanks to better technology. What stood out most to me was how much both imports and exports matter to keeping this industry running, especially for smaller manufacturers who still rely on imported materials. Supporting them through lower trade barriers seems really important moving forward.

This showed me the substantial change in U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing over the years. I learned that most U.S. apparel factories are tiny, and most of their products are samples or prototypes, which cannot compete with big factories overseas. Another thing is that I did not realize how high-tech textiles, such as medical fabrics and nonwovens, were driving the growth in the United States. That surprised me, and I would say changed my mind, regarding “Made in the USA” being all about specialized products, rather than everyday clothes.

After reading this blog post I have a better understanding of the textile and apparel manufacturing industry in the US. The US has taken a shift towards focusing on high tech textile production rather than traditional clothing. This makes sense for the US because they will have a better competitive advantage in creating protective clothing, medical, or industrial use textiles because this sector is where the US saw the most growth in domestic and international export markets. Additionally, I learned about the state of US factories and employment rates in recent times. The US industry is dominated by micro-factories that often have less than 10 employees which shows that the US should continue to focus on specific textile products, like the high-tech textiles, where small-scale production is more feasible. The US industry is steady but could never compete with overseas manufacturers that can create traditional clothing in large scale models.

This blog post helped me understand that the U.S. textile/apparel industry has shrunk a ton over the years, but what’s left has moved into more high-tech textiles instead of clothing. What I didn’t realize was that “Made in the USA” could just be the fabrics, not actual clothes. I did’t realize this before and I’m sure a lot of people reasing their tags that say “Made in USA” just assume everything was made here, but thats not the case. U.S. apparel factories are tiny micro-factories, mostly for samples, and they won’t be able to replace cheap labor due to importing from other countries such as China. There are less jobs in the fashion manufacturing business because technology makes production faster and more efficient, and most of the jobs in the fashion sector are in retail, not manufacturing. Even though people think “Made in the USA” means no imports, the industry still depends on global trade heavily.

This article is helpful to understand where the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing industry stands today. It is surprising to me that, as of 2024, employment in textile and apparel manufacturing dropped to only about 270,700, representing a steep decline since 2019. Additionally, the article highlights the fact that U.S. manufacturing has shifted towards high-tech textile products, such as medical fabrics, as garment production is decreasing.This definitely shows how the U.S. textile industry isn’t disappearing, but rather transforming and moving towards a more specialized production. However, this recent shift poses a challenge for domestic garment manufacturers due to their increased reliance on imported components. Overall, this article does a good job of explaining the current state of the U.S. textile and apparel industry, and the changes it has faced.

This article helped me understand how U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing has changed, not in the sense of “bringing jobs back,” but in how the industry has completely shifted its focus. What stood out most is that “Made in the USA” today is mostly about high-tech textiles, like medical fabrics, protective gear, and nonwovens, rather than mass-produced clothing. The data showing that most U.S. apparel factories have fewer than ten employees proves what we talk about in class, where domestic production can support prototypes and small runs, but it can’t replace global sourcing or compete with factories in places like Bangladesh or Vietnam that employ thousands. I also found it interesting that while employment keeps falling, productivity keeps rising because of automation and new technology. The article shows that U.S. manufacturing still depends heavily on trade, exports to the Western Hemisphere and imported components for smaller factories. This showed the future of U.S. production isn’t about replacing imports but about specializing, innovating, and staying globally connected.

This article gave me a much clearer picture of how the U.S. textile and apparel industry is evolving. I was especially struck by the fact that even though manufacturing employment has continued to decline, certain sectors like yarns and fabrics are showing resilience. It really highlights how the industry is shifting away from traditional mass-market apparel toward more specialized, high-tech textile products.

I also found it interesting that most U.S. apparel factories today are micro-factories focused on samples or small-batch production. It reinforces why domestic production alone can’t replace global sourcing, especially for high-volume goods. Overall, the article shows that U.S. manufacturing isn’t disappearing, it’s transforming. The insights were super helpful for understanding sourcing and trade in today’s market.

This article was really interesting because it shows how much the U.S. apparel and textile industry has shifted. Especially toward high-tech textiles instead of everyday clothing. It challenges the assumption that domestic manufacturing could replace imports, since most U.S. apparel factories are micro-scale and mainly produce prototypes rather than mass-produced garments. I think the point about tariffs is especially important and that applying heavy tariffs on imported clothing hurts retailers and consumers when we simply don’t have the capacity to make those goods at scale here in the U.S. Meanwhile, the growth in areas like non-wovens and industrial textiles suggests that the real opportunity for “Made in the USA” lies in specialized textile innovation, not trying to recreate large-volume garment production that other countries are better equipped for.

To enhance the information in this article, the patterns of change within the U.S. textiles and apparel industry were significant to note, as consumers are seeing more “Made in the USA” products that ultimately demonstrate an evolution towards high-tech production over mass-market apparel manufacturing. Textiles now contribute to a large majority of domestic output, indicating companies choosing innovation over volume, which is a big environmental initiative in the U.S. fashion industry. This delegating of investments is evident in the increased growth of nonwovens as these products continue to expand despite the broader textile industry slowing down. Likewise, the transitions to smaller-scale apparel factories represents the U.S. textile and apparel industry prioritizing customization and efficiency over mass production. To echo some points made previously, by avoiding over-production, companies are helping to limit the amount of waste that is generated. With these strategies it makes it difficult for foreign countries to replicate and keeps companies manufacturing from within as these companies produce their products in a more ethical manner. The most essential takeaway from this article is that domestic competitiveness drives from capital-intensive operations over cheap labor. This is evident in the larger scale of some textiles mills in the U.S., meaning those who are capable of using innovative equipment are the ones who are growing. What this translates to is that the overall concept of advanced textiles are the reason for the more recurring “Made in the USA” tags on garments.

The U.S has shifted into high-tech textiles and is allowing us to move up in the value chain. This goes hand-in-hand with what we have been discussing in class about competitive advantage. Being able to produce high-tech products is an advantage, because not every country will have the skills to do so. With that being said, the U.S can not be self sufficient because they do not have the competitive advantage for every aspect. We depend heavily on exports as much as we do with imports. One thing I didn’t realize was how many workers there actually are in U.S factories. We hear about overcrowded factories on our seas, but some U.S factories have 10 workers. In the future will we be able to have more competitive advantages, or will we only be known for tech textiles?

The U.S. textile and apparel industry is changing a lot. Textile and apparel manufacturing in the U.S. has decreased, but the United States stays strong because of strategic use of globalization. The structure of U.S. textile and apparel has increased from 1998 to 2023. Made in the USA focuses mainly on textile products that accounted for 83% of the total output. This is interesting because it shows that the U.S. is making fewer clothes than before but has found new ways to stay strong in the competitive fashion industry. It is surprising to see how the industry has shifted into making textiles further showing how smart the U.S. is in competing in a global market without needing to produce clothing domestically. Most U.S. apparel factories only produce samples or prototypes. The article also shows how important trade is. The U.S. relies heavily on both imports and exports. This article really showed how the U.S. stays strong in a competitive industry even without creating garments.

Even though people always say U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing is “dying,” the industry is actually shifting, not disappearing. Production has stayed pretty steady, and a lot of that is because “Made in the USA” now focuses more on high-tech textiles than regular clothing. Things like medical fabrics, protective gear, and nonwovens are growing fast and even boosting exports. Apparel manufacturing in the U.S. looks totally different now too. Most factories are tiny micro-factories, usually fewer than 10 employees, so they’re making samples and small runs, not replacing overseas production. Employment keeps dropping, but mainly because technology is making workers more productive. And interestingly, both imports and exports are essential for keeping U.S. companies running. Many smaller manufacturers even rely on imported materials. Overall, the industry is evolving into something more specialized, tech-driven, and global, not going away anytime soon.

I really liked the visuals in this blog. I feel like they were able to clarify the facts and information given. The charts, especially. I think they were able to show readers a clear view of the US manufacturing system. It also shows how fast things can change within this industry, especially with how fast the textile and apparel trading and manufacturing are changing.

This article emphasizes how imports and exports support the U.S manufacturing sector, showing that it depends on exporting textiles and importing apparel. By lowering trade barriers, the U.S manufacturers can remain competitive in the market.

I think the employment data is interesting since it shows a rise in productivity which reduces labor needs even though exports remain the same.

A key concept from our class that relates to this blog post is the Factor Proportions Theory. This trade theory discusses that countries gain comparative advantage based on their relative abundance of production factors. This theory primarily discusses capital and labor, being that ‘capital-abundant’ countries specialize in ‘capital-intensive’ goods, while ‘labor-abundant’ countries specialize in ‘labor-intensive’ goods.

The blog post strongly reflects this theory, as the US is a capital-abundant country and is increasing in specialized high-tech and industrial textiles such as nonwoven fabrics, medical textiles, and specialty fabrics. For example, nonwoven fabric production increased by 12.32% between 2019 and 2022, outperforming the overall textile industry. Meanwhile, apparel manufacturing, which is traditionally labor-intensive and remains one of the most dominated by micro-factories in the US. While large-scale garment production continues in labor-abundant countries like Bangladesh. This supports the idea that the US no longer holds comparative advantage in labor-intensive apparel production but does in capital-intensive textile innovation.

With the goal of creating new jobs and prioritizing US made goods, US fashion companies should continue investing in advanced textile technologies rather than attempting to reshore mass apparel production. Policymakers, meanwhile, should focus on reducing trade barriers for imported inputs in order to strengthen globally integrated supply chains that align with U.S. comparative advantage.