William L. “Bill” Jasper has been Unifi’s Chairman of the Board since February 2011 and has served as Unifi’s Chief Executive Officer (CEO) and member of Unifi’s Board of Directors and the Company’s Executive Committee since September 2007. Prior to his role as Chairman of the Board, he served as President and CEO, Vice President of Sales and General Manager of Unifi’s polyester division. He joined the company with the purchase of Kinston polyester POY assets from INVISTA in September 2004. Prior to joining Unifi, Mr. Jasper was the Director of INVISTA’s DACRON® polyester filament business. Before working at INVISTA, he held various management positions in operations, technology, sales and business for DuPont since 1980.

Bill Jasper is also a University of Rhode Island alumni! He graduated in 1977 with a Master of Science in Mechanical Engineering.

Founded in 1971 and Headquartered in Greensboro, NC, Unifi, Inc. is a leading producer and processor of multi-filament polyester and nylon textured yarns. Unifi provides innovative, global textile solutions and unique branded yarns for customers at every level of the supply chain. Unifi’s core business consists of the manufacturing of POY (partially-oriented yarn), the texturing, air-jet texturing, twisting, and beaming of polyester and the texturing and covering of nylon filament yarns. Branded products of Unifi include aio® — all-in-one performance yarns, SORBTEK® A.M.Y.®, MYNX® UV, REPREVE®, REFLEXX®, INHIBIT® and SATURA®, which can be found in many products manufactured by the world’s leading brands and retailers.

Interview Part

Sheng Lu: How would you describe the current status of the U.S. textile industry? What’s your outlook for the industry in the next 5 years? What are the top challenges the U.S. textile industry is facing?

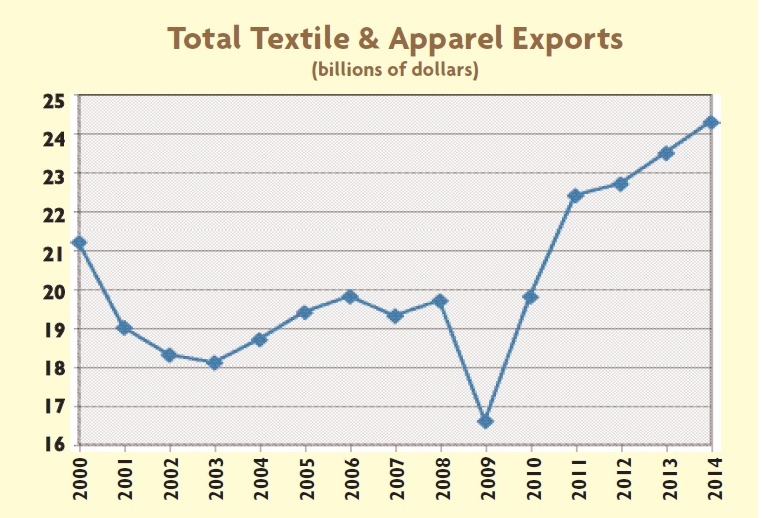

Bill Jasper: The industry has undergone a revival after years of decline, so the current status is strong and I believe we’ll see that environment continue for several more years in this region. The industry is expanding in practically every key economic indicator, including output, employment, exports and investment.

- U.S. textile shipments topped $56 billion in 2013, up more than 5% from 2012

- U.S. textile exports were $17.9 billion in 2013, up nearly 5%

- The U.S. has also enjoyed an investment surge in new plants and equipment. Over the past year, 8 foreign companies have made public announcements regarding their intention to invest more than $700 million in new U.S. textile facilities and equipment. These investments are projected to provide approximately 1,900 new jobs in North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia and Louisiana.

- This $700 million does not include the ongoing re-investment activities that domestic textile companies have made.

The U.S. industry is also benefitting from several domestic advantages, including reliable and relatively inexpensive energy supplies, infrastructure, access to raw materials, and proximity to markets. We are gaining competitive advantages due to conditions outside the U.S., including rising costs in Asia, high shipping costs, and port capacity restraints. In addition, you’ve probably seen Wal-Mart’s advertising and P.R. blitz that it is committing to buy hundreds of billions of additional dollars in American-made products over the next decade to help support and spur U.S. manufacturing and innovation. With Wal-Mart leading the way, there is definitely a movement afoot to “reshore” some U.S. manufacturing, including textiles and apparel.

Finally, I believe a major driver of recent investments and one of the biggest contributors to the renaissance described above is also one of the biggest challenges the industry is facing. Virtually all of our free trade agreements to date have been based on a yarn forward rule of origin. This means that all processes, including the yarn extrusion, spinning, texturing, fabric formation, and the dyeing, finishing and assembly of the finished garment must take place in a free trade agreement member country to receive duty-free benefits. This rule has benefited the U.S. industry especially in NAFTA and DR-CAFTA, as U.S. yarn and fabric producers have dramatically increased our exports to the region under this regime.

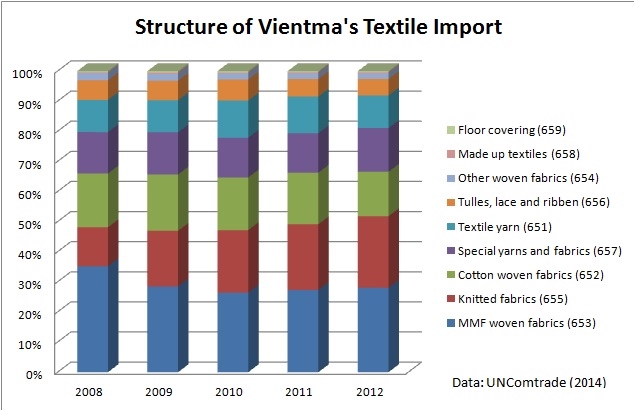

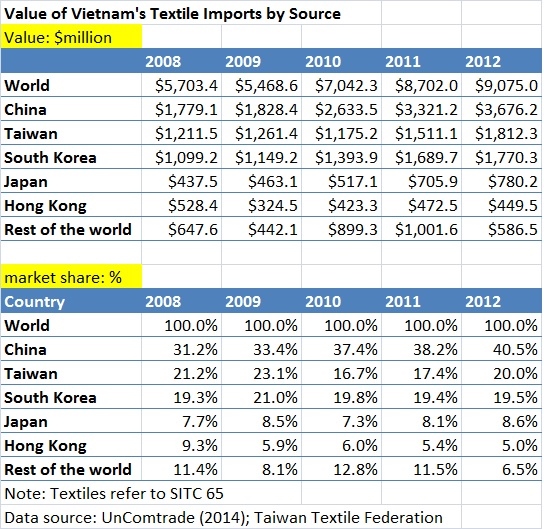

As the U.S. negotiates the Transpacific Partnership Agreement (TPP), if this same rule of origin is undermined by single transformation rules or other loopholes, it could erode the entire supply chain in this hemisphere. In addition, careful attention must be paid to market access for potential TPP members like Vietnam, who is already the second largest exporter of textiles and apparel to the U.S. The domestic industry has requested reasonable duty phase-out periods in market access for our most sensitive products under the TPP so that our partnerships in this region have an adequate adjustment period. The TPP is considered to be the model for all future trade agreements with the U.S., thus it is critically important that our negotiators consider the profound consequences it can have on U.S. jobs and the U.S. textile industry.

Sheng Lu: “Made in USA” is a very hot topic these days, yet we also live in a globalized world today. From the textile business perspective, what is the relationship between “Made in USA” and “going global” in the 21st century? Do US textile companies today still have to make a choice between the two?

Bill Jasper: Most apparel brands and retailers utilize a balanced sourcing strategy that incorporates production in this hemisphere, as well as Asia, Africa, or other global manufacturing and/or assembly. I do not feel that U.S. textile producers today must necessarily make a choice between the two, but must have a business plan that addresses the realities of the global market. In fact, nearly 98 percent of the clothing purchased in the U.S. is imported from abroad. Only two percent of clothing bought in this country is manufactured here in the U.S., and I doubt there is a business plan in any U.S. textile company that doesn’t reflect that reality.

Unifi, for example, works with downstream customers who want research and development, innovation, speed to market, sustainability, etc., from yarn and fabric production in this hemisphere. It is important that we provide flexibility and these same innovative products anywhere in the world our customers choose to do business. Thus, we export yarn to more than 30 countries from our domestic plants (not counting the exports of fabric from domestic weavers and knitters that use our inputs). Unifi also operates a wholly-owned subsidiary in Suzhou, China, where we focus on the development, sales and service of Unifi’s premium value-added yarns for the Asian market. Our expanding network of manufacturing facilities, sales and sourcing initiatives enables us to drive and capture growth in every major textile and apparel region in the world.

Sheng Lu: We know many products of Unifi are textile intermediaries like fibers and yarns. So how is Unifi’s brand promoted? How much can consumers recognize your product as “made in USA”?

Bill Jasper: As an upstream producer, making that connection with the ultimate consumer can be a challenge. Unifi has succeeded on several fronts. We have differentiated our product offering with premium value-added products, like REPREVE®, which we supply to our global customers wherever they are producing. Our downstream sales and marketing teams work extensively with brands and retailers to help them promote the unique properties of Unifi fibers and yarns. Some ways we do this includes, on product-labeling, hangtags, point of sale, cobranding, advertising and various consumer promotions. The “Made in the USA” message is and can be part of this effort, and I think we’ll see more demand for that as the brands and retailers move more of their sourcing from Asia back to this hemisphere over the next few years.

We recently began marketing directly to the consumer through the launch of our REPREVE #TurnItGreen campaign, which focuses on raising awareness around the importance of recycling and the products that can be created from plastic bottles when they are recycled. The initial launch took place at ESPN’s X Games Aspen in January 2014, where we literally and figuratively helped turn the event green using REPREVE-based product and color. At X Games Aspen, we recycled more than 100,000 plastic bottles to make X Games signage, lanyards and other merchandise. As we grow the REPREVE brand at retail and in the consumer space, we will continue these efforts with various partners, including current partners who have joined the REPREVE #TurnItGreen initiative, including NFL team, the Detriot Lions, where we will recycle more than 200,000 plastic bottles to help turn their stadium green on December 7th, 2014. We’re also driving recycling education by helping turn the live action event, Marvel Universe Live!, green through apparel for the cast and crew, merchandise items and banners, all made with REPREVE recycled fiber.

Sheng Lu: Unifi has opened factories in Brazil and Colombia. Why did Unifi decide to invest in South America? What is the connection between Unifi’s US-based operation and your operations in South America?

Bill Jasper: Both of these manufacturing plants were established in the mid to late 90s as wholly owned subsidiaries of Unifi, Inc. We purchased the small Colombia plant to give us more spandex covering capacity for our yarns that come back to the U.S. for use in pantyhose and socks. The Brazil operation was set up when we saw an opportunity to capture a share of the growing synthetic apparel market in that country. The majority of the textured polyester we make in Brazil stays in Brazil. Over the past several years we have introduced our premium value-added yarns in that market and hope to see strong growth in those product lines as the economy picks up down there.

Unifi also opened a 120,000 square foot polyester yarn texturing facility in El Salvador in 2010 to take advantage of the duty benefits in the DR-CAFTA trade pact and to better serve our growing customer base in the region.

Sheng Lu: What is the market potential of Asia and particularly China for Unifi and the US textile industry in general?

Bill Jasper: The expected growth in China and other Asian markets is enormous, and Unifi’s strategic plan reflects that. By 2020, China’s consumer market is expected to reach 22 percent of total global consumption, second only to the U.S. at 35 percent. Our wholly owned subsidiary (UTSC) is located at the center of one of China’s most important textile regions, Suzhou. UTSC customers will have quick access to new product introductions with the quality and technical service they have come to expect with Unifi. UTSC was established to provide the domestic Chinese market with a full complement of our specialty branded products, not only for their growing appetite for branded apparel, but for growth in their automotive and home furnishing markets.

The U.S. textile industry in general has invested heavily to take advantage of the growth in Asia by adding to their manufacturing facilities here or putting plants in Asia or China. Countries like Vietnam also offer strong manufacturing platforms due to lower wages than China and the prospect of duty-free exports to the European Union, the U.S. and Japan when announced trade agreements like TPP are completed. The growth of the Asian textile market certainly ups the ante in regard to whether there will be a yarn forward rule under TPP. Failure to include a strong yarn forward rule in this key agreement will likely cede key Asian markets to textile suppliers that are not a party to the TPP. To the contrary, inclusion of a yarn forward provision in that agreement will drive investment to partner countries and provides opportunities for U.S. fabrics and yarns to supply production meeting those guidelines.

Sheng Lu: How do you see “sustainability” as a game changer for the textile industry? What has Unifi done in response to the growing awareness of sustainability among consumers?

Bill Jasper: Reducing our environmental footprint through the entire supply chain has been an important focus of the industry for several years, driven by industry leaders like Unifi and our suppliers and customers.

Unifi has an on-site environmental team constantly reviewing everything we do to see how we can reduce, reuse, recycle and conserve. All of our U.S.-based plants are currently landfill-free; we recycle our shipping pallets, we have installed energy-efficient lighting and increased efficiency around our compressed air usage, for example.

In 2010, Unifi opened our state-of-the-art REPREVE Recycling Center, where we use our own industrial yarn waste, recycled water bottles and even fabric waste to make REPREVE® recycled polyester fibers and yarns which go back into high end consumer apparel, like fleeces made by Patagonia, shoes and apparel by Nike, The North Face jackets, and eco-friendly Haggar pants. You can also find REPREVE® in Ford vehicles, including the 2015 Ford F150. In 2013, REPREVE® turned more than 740 million recycled bottles into fiber, and since 2009, we have recycled more than two billion plastic bottles to make REPREVE. Unifi’s recycled process offsets the need to use newly refined crude oil, uses less energy and water, and produces fewer greenhouse gas emissions compared to making virgin synthetic fibers.

Moreover, for Unifi at least, this is much more than a marketing concept. Our focus on environmental sustainability is now an engrained part of our culture. We believe that sustainability must be an unwavering core value of responsible manufacturing in the 21st century.

Sheng Lu: Given the changing nature of the US textile industry, what kind of talents will be most in needs by the US textile industry in the years ahead? Do you have any advice for textile and apparel majors in terms of improving their employability in the job market?

Bill Jasper: The U.S. textile industry is a diverse, technology driven, capital intensive, innovator of high quality products that is able and ready to compete effectively in the 21st century global marketplace, and a prepared workforce is critical in meeting the needs of this competitive industry. Not only do we look for skills in textile technology, we look for workers with high math and science aptitudes, technical and chemical engineering skills, process improvement, and industrial engineering capabilities. The ability to think strategically and globally is a big advantage in driving sales and creating marketing programs that meet the needs of our customers world-wide.

–The End–