Background

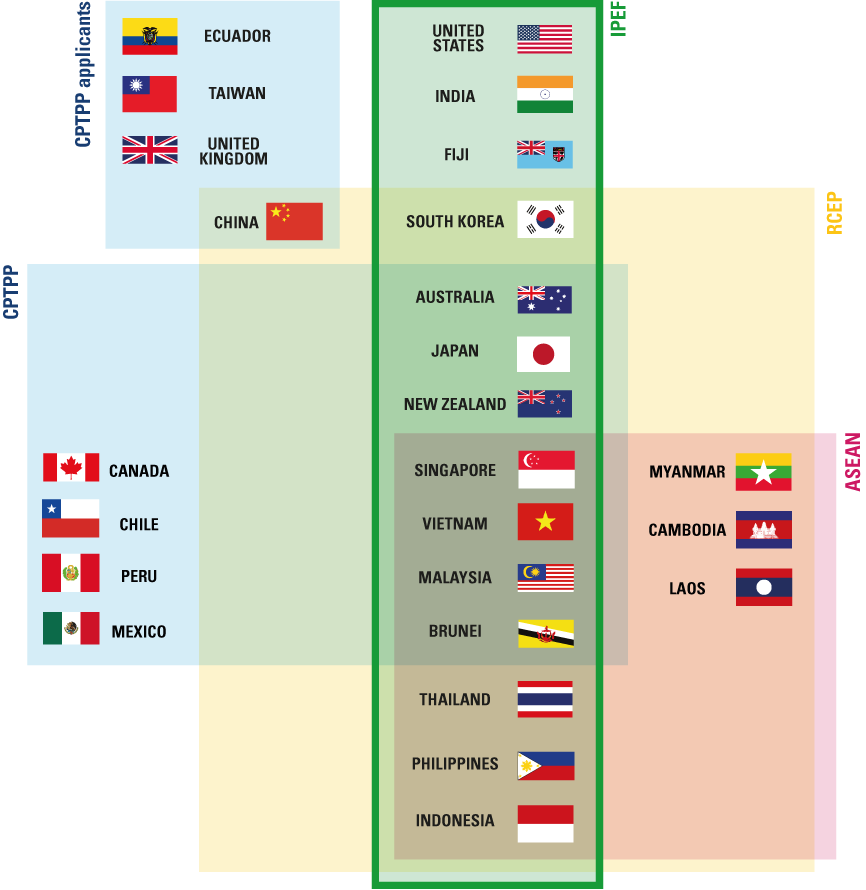

The Asia-Pacific region includes several mega free trade agreements:

ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) is a regional intergovernmental organization comprising ten countries in Southeast Asia (Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam). In 2021, ASEAN members have a combined GDP of $3.11 trillion and a population of 673 million.

CPTPP (Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership) is a free trade agreement signed by 11 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including Japan, Malaysia, Vietnam, Australia, Singapore, Brunei, New Zealand, Canada, Mexico, Peru, and Chile. The CPTPP covers a market of 495 million people with a combined GDP of $13.5 trillion in 2021. The United States was originally a participant in the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) negotiations, but in January 2017, former US President Trump withdrew the US from the agreement. The Biden administration has indicated no interest in rejoining CPTPP. Additionally, China is actively seeking to join CPTPP.

RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) is a free trade agreement signed by 15 countries in the Asia-Pacific region, including China, Japan, South Korea, Australia, New Zealand, Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, Vietnam. In 2021, RCEP members collectively represented a market of 2.3 billion people with a combined GDP of $26.3 trillion. India was an RCEP member but withdrew from the agreement due to concerns about import competition with China.

IPEF (Indo-Pacific Economic Framework for Prosperity) is a US-led economic cooperation framework that aims to “link major economies and emerging ones to tackle 21st-century challenges and promote fair and resilient trade for years to come.” IPEF is NOT a traditional free trade agreement, and it does not address market access issues like tariff cuts. Instead, IPEF includes four pillars: trade, supply chains, clean economy, and fair economy. IPEF members in the Asia-Pacific region include the United States, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, India, Fiji, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. The IPEF is designed to be flexible, meaning that IPEF partners are not required to join all four pillars. For example, India chooses not to join the trade pillar of the framework. In 2021, IPEF countries collectively represented a market of 2.1 billion people with a combined GDP of $23.3 trillion. The potential economic impact of IPEF remains too early to tell.

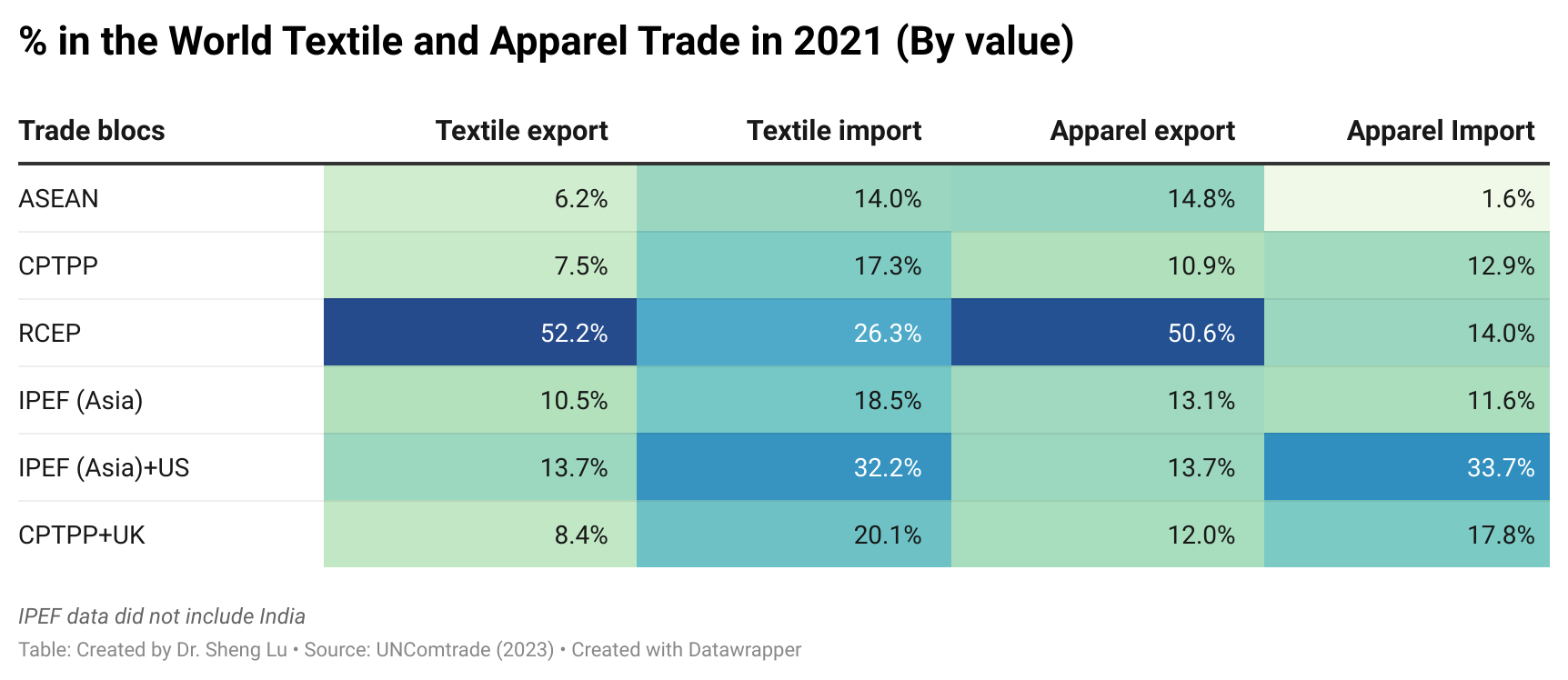

Notably, ASEAN, CPTPP, RCEP, and IPEF members play significant roles in the world textile and apparel trade. Specifically:

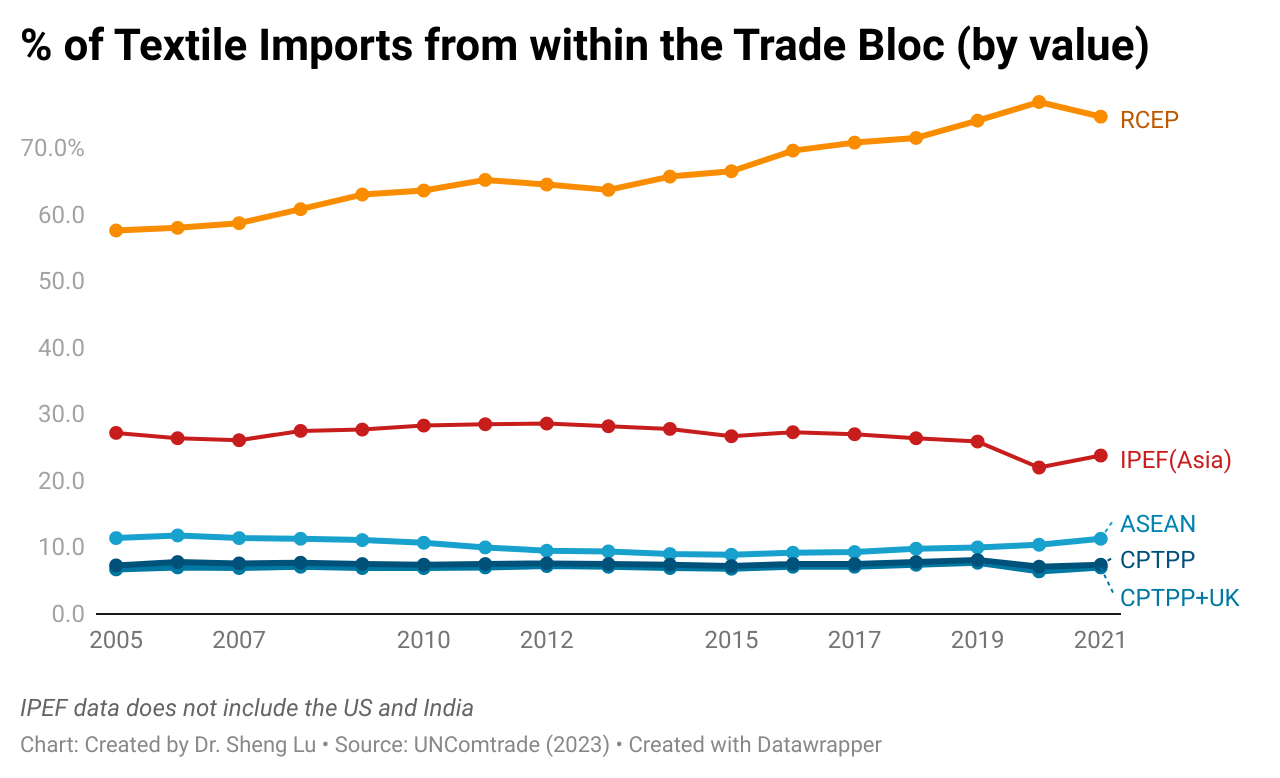

ASEAN and RCEP members have established a highly integrated regional textile and apparel supply chain. For example, a substantial portion of ASEAN and RECP members’ textile imports came from within the region.

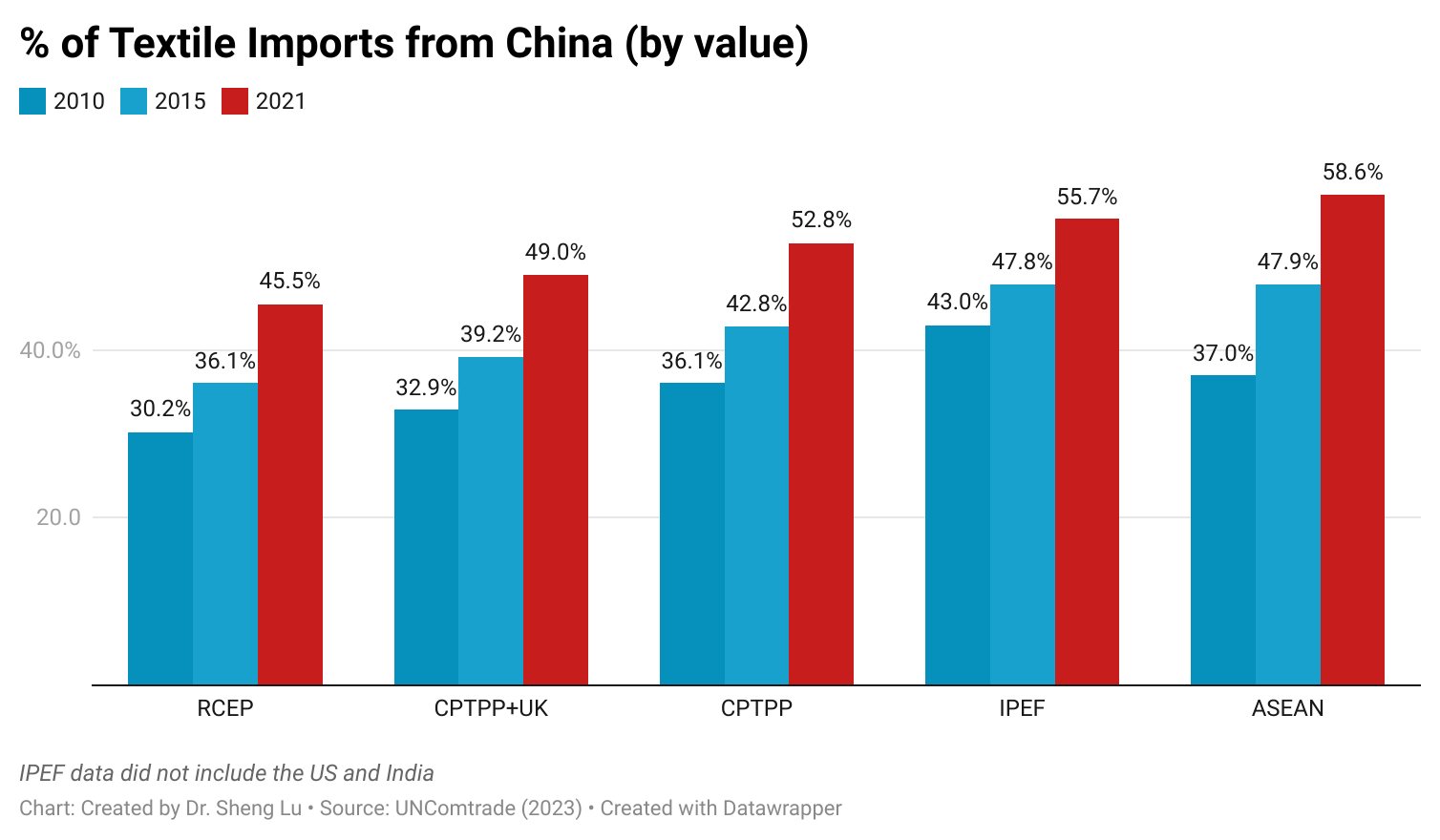

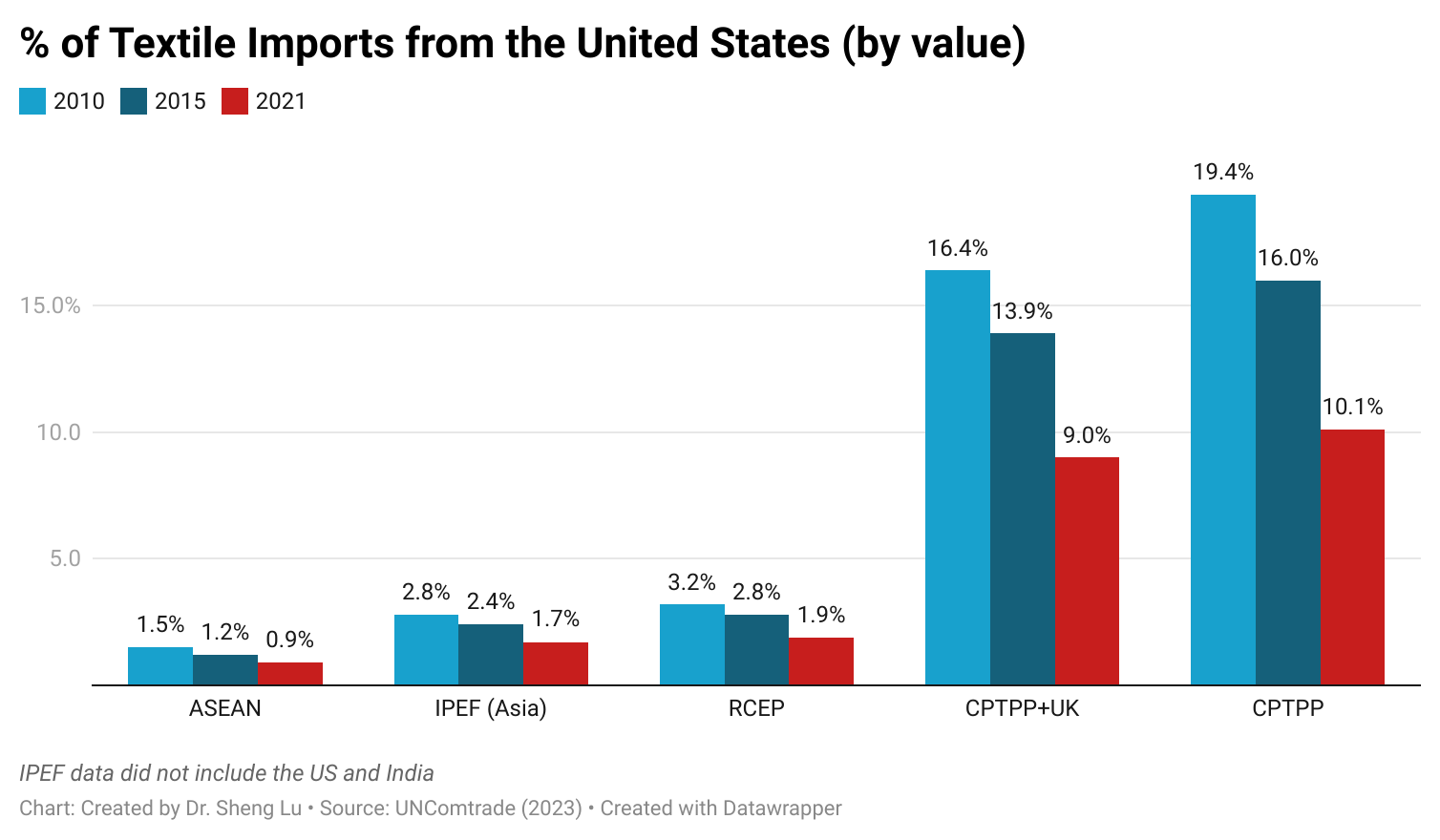

ASEAN and RCEP members’ supply chain connection with China has substantially strengthened over the past decade. In contrast, the US barely participated in Asia-based textile and apparel supply chains. For example, other than CPTPP, the US accounted for less than 2% of ASEAN, RCEP, and IPEF members’ textile imports in 2021.

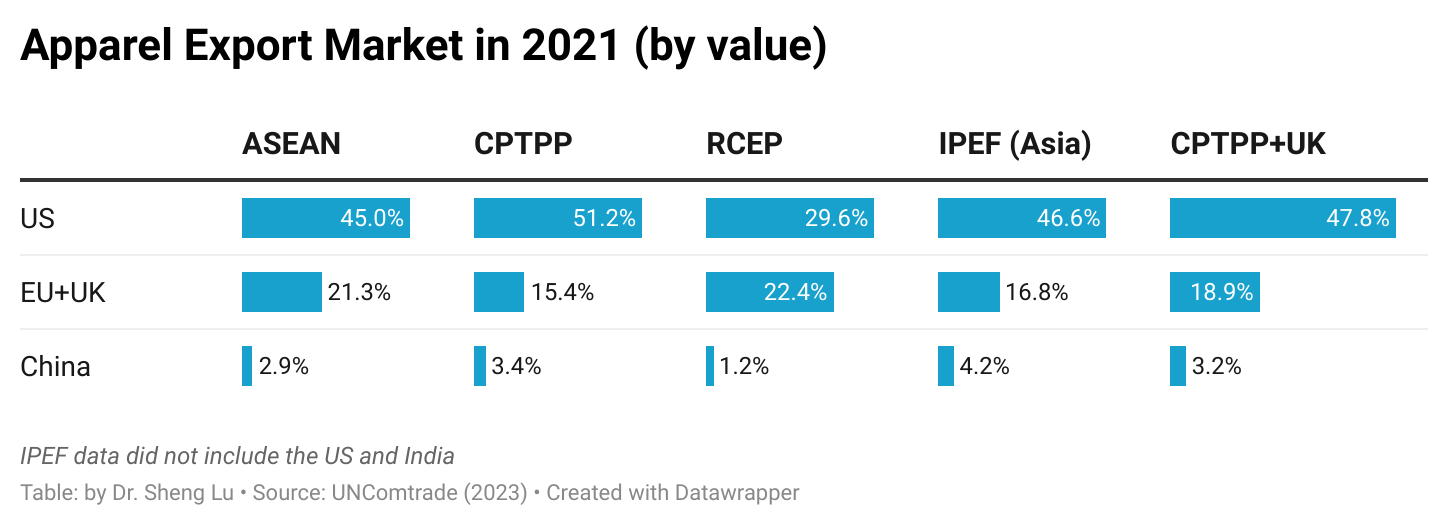

ASEAN and RCEP members also hold significant market shares in the world textile and apparel export (over 50%). Meanwhile, the US and EU are indispensable export markets for ASEAN and RCEP members.

Because of the United States, IPEF represented one of the world’s largest apparel import markets (i.e., 33.7% in 2021, measured in value). Similarly, in 2022, about 26% of US apparel imports came from current IPEF members. Should IPEF address market access issues, it could potentially offer significant duty-saving opportunities for textile and apparel products.

Additionally, UK’s membership in CPTPP may have a limited direct impact on the textile and apparel sector, at least in short to medium terms. For example, current CPTPP members only accounted for about 6% of UK’s apparel imports in 2021.