Many brands and retailers are trying to make their apparel sourcing more sustainable, from publishing the ESG report to using more recycled textile materials in the products. However, the effectiveness of fashion companies’ sustainability efforts and related communication remain largely unknown, especially among Generation Z, their most important target market.

Students in FASH455 and FASH graduate students recently shared their valuable perspectives on sustainable apparel sourcing with Just-Style, a leading publication focusing on the fashion industry. Below are selected original comments from students:

What “sustainable apparel sourcing” means to you and your generation, Generation Z?

Cecilia Goetz, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors), Senior

To me, sustainable apparel sourcing means going about sourcing in an ethical way both environmentally and socially and often putting the financial interests of the company on the backburner in order to do so. This can mean a number of things, including a shift towards more local production (nearshoring), the implementation of labor regulations in factories, and the use of more eco-friendly materials. On top of this, it is a matter of companies being entirely transparent with their efforts and being open with consumers about where their products came from and how they were made. Part of sustainability involves doing everything in a company’s power to support people and the environment, and the other part involves telling consumers the entire truth, whether it works in their favor or not. I think a large portion of Generation Z has a strong understanding of “sustainable apparel sourcing,” but there are still so many young consumers who are never faced with the question of how to define it and how to achieve it. My generation is definitely one that is more progressive and well-informed regarding social issues than the Baby Boomers, for example, but there is definitely still a long way to go in terms of educating Gen Z on sustainable practices within the apparel industry.

Emilie Delaye, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

It is difficult to share exactly what “sustainable apparel sourcing” means to me and my generation, as I feel the meaning and interpretation of the word “sustainable” itself is changing and expanding rapidly. A few years ago, probably 5-10 years ago, the phrase sustainable apparel sourcing referred to sustainable efforts in terms of the environment. This meant that products were perceived as sustainably sourced when they met some of the following characteristics, including: using inputs that are biodegradable components from natural or recycled fibers, inputs that have no chemical treatment use, or inputs that were produced with the effort to reduce overall carbon footprint. I think now, my generation is viewing “sustainable sourcing” as a phenomenon that is much larger than environmental issues. There are many more intricate issues that intertwine with sustainable sourcing that go beyond purely environmental focuses, including social and ethical factors. Gen Z consumers, including myself, are becoming more concerned with the “who” and “where” questions in sourcing. This means that consumers view sustainable sourcing as things such as sourcing from responsible production facilities that pay fair wages or avoiding sourcing in areas with large social or ethical issues.

Hannah Laurits, Graduate Student, Fashion and Apparel Studies

For Generation Z, the concept of “sustainable apparel sourcing” embodies a commitment to ethical, eco-conscious, traceable, and transparent sourcing practices. Sustainability encompasses various elements that define responsible production. It depends upon the ability to trace the origins and production methods of products, emphasizing fair labor practices across all tiers of the supply chain. Our generation greatly emphasizes environmental preservation and recognizes the importance of protecting our earth’s natural resources for future generations.

A sustainable supply chain operates with a determination to minimize adverse environmental impacts by harnessing emerging innovations in materials and processes. To Generation Z, a product can earn a sustainable label or association by meeting a portion of these criteria. Realistically, we understand that perfection in sustainability remains nearly impossible to achieve today. Nevertheless, as a generation, we actively seek products that align with as many of these sustainability parameters as possible and validate their claims with reliable evidence. To Generation Z, sustainable sourcing is about driving positive change in the fashion industry through our apparel supply chain.

Miranda Rack, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors) & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

Sustainable apparel sourcing means knowing where textiles and apparel come from and who made it. Consumers are starting to consider this information when buying clothing. The country-of-origin label does not provide enough information to learn anything about the garment. Especially because the country-of-origin tag only displays where the garment was finished, consumers receive no information on where the fibers or fabric was sourced. While it is common for brands to share their tier 1 suppliers, consumers want more information than that. We want to know which factories produced what, and especially who made our clothing. If a brand wants to source apparel more sustainably, the first step is to become more transparent. Brands should be required to publicize all steps of their supply chain. Consumers value supply chain transparency because it builds a sense of trust between brand and consumer. It is the brand’s responsibility to be open and honest about where their products come from, not the consumer’s job to research every time they shop.

Kendall Ludwig, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

It means full responsibility for their supply chain. From start to finish, a company knows who makes their products and ensures that the garment workers they employ have access to basic human rights such as a living wage and the right to unionize. On top of this, the company should ensure that the health and safety of their workers are not at risk. If human rights abuses appear in their supply chain, the company must remediate them. From an environmental perspective, sustainable apparel sourcing also means that a company has implemented a plethora of strategies to minimize the harmful environmental impacts their business creates. Further, social and environmentally sustainable apparel sourcing requires transparency from apparel companies. If a company does not disclose their efforts, it is valid to assume they have none. The more transparent, the better!

Leah Marsh, Graduate Student (4+1 program), Fashion and Apparel Studies

Gen Z has become increasingly aware of the global fashion industry’s harmful effects on the environment. With this, a majority of us have turned towards the topic of sustainability in order to purchase clothing and support companies that cause minimal harm. Our understanding of “sustainable apparel sourcing” includes both environmental and social topics. We believe that companies who sustainably source their apparel products are paying their workers fair wages and, protecting their health and safety, and also respecting their local environments by minimizing their output of pollutants and being mindful of limited resources. These are just a couple of specific examples, but we also care about topics such as economic circularity, local production, and consumer education. Ultimately, to Gen Z, sustainable apparel sourcing means not only producing clothing with minimal negative environmental and social impacts but also being transparent and responsible throughout the entirety of the supply chain. Gen Z consumers are continuously looking for fashion brands and companies to support that align with these values. It is important to me and my generation to support those who make genuine efforts to create a more sustainable and ethical fashion and apparel industry.

Annabelle Brame, Fashion Design & Product Innovation Major, Senior

When asked how we Gen Z interprets “sustainable apparel sourcing” the first thing that comes to mind is sustainability for workers. I think it is so easy to confuse sustainability with environmental consciousness. And while that is a piece of it, the ethical element is wildly important. Since most companies outsource production from other countries with more labor, we are very conscious of how that looks for the workers. We see employees not being fairly paid with poor working conditions, which is not only sickening but wildly unsustainable. And while there is so much talk about the poor conditions, that is how we encourage the shift to more sustainable practices. Sustainability in apparel sourcing starts to look at fair wages, manageable hours, and safe working conditions. This isn’t a one-person job. It takes companies, the government, and factory owners to make that change physically.

Hunter Wills, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

Sustainable apparel sourcing means that you know exactly where a garment is coming from, you are able to easily learn about the supply chain if you would like to do further research, and you know everyone in the process is being treated ethically. When brands try to hide information about their supply chain, it usually means they are not practicing sustainable sourcing, whereas companies that are very open and transparent about this process are more likely to be sustainable.

How does a fashion company’s sustainability in apparel sourcing affect your purchasing decisions?

Cecilia Goetz, Fashion Merchandising and Management (Honors), Senior

I am embarrassed to admit that in high school, I shopped at brands like Shein and Forever 21 before taking any classes, especially about fashion and sustainability. As a teenager with little money of my own and virtually no knowledge of what goes on behind the scenes before a garment arrives at your doorstep, the low prices and trendiness of clothing was my main priority. Unfortunately, I think that is the case for a lot of young consumers, which is why brands like Shein perform so well. Now, after years of specially curated classes about the fashion industry, I have learned about the Rana Plaza Collapse of 2013, the chemicals and water used in the production of a single t-shirt, the wages for garment workers in less developed countries, and so much more. As a result, the sustainability of a brand is something I really look into when shopping. Whether it be the hang tags on a garment calling out recycled materials, an online tab about sustainability initiatives, or a hanger made from eco-friendly materials, I am always more inclined to make a purchase from a brand when I see these things. I do, however, also try to weary of vague references to ethical or environmentally sound practices because not all companies tell the whole truth when advertising the sustainable aspects of their products.

Emilie Delaye, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

I think that a fashion company’s sustainability in apparel sourcing does affect my purchasing decisions, however, I believe that I am more informed than the typical Gen Z consumer. Though it is becoming increasingly popular for consumers to be educated on the processes, such as sourcing processes, that go into their apparel production, I do not believe we are at a point where the average consumer understands or has the background knowledge to know what the implications of brand’s sourcing decisions have. By studying the fashion industry in school, I have had access to this knowledge, and therefore have changed my shopping behavior. I tend to lean more towards thrifting clothing, as most sustainable brands that seem compelling fall sadly out of the price range of a college student’s tight budget. For me, thrifting from local consignment stores is a way for me to “boycott” the larger fast fashion brands and choose a relatively lesser evil.

Hannah Laurits, Graduate Student, Fashion and Apparel Studies

A company’s reputation and commitment to sustainable sourcing practices significantly influences my purchasing decisions. When I shop, I try to practice conscientious consumption, taking into account that company’s reputation and what the impact of that article of clothing may be. Being well-informed about the practices of the brands I support is crucial to me, as I feel it is my responsibility to ensure I am buying from a company that is dedicated to maintaining a sustainable supply chain. When I am unsure, I tend to do more research into the brand to see how transparent they are about their practices. When purchasing a clothing item, I strategically look for brands that are doing their part in this industry’s efforts to improve their environmental and social impacts. While I don’t expect absolute perfection in a company’s sustainability practices, I remain vigilant for warning signs, such as greenwashing or a lack of information, that may raise doubts about their authenticity.

Miranda Rack, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors) & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

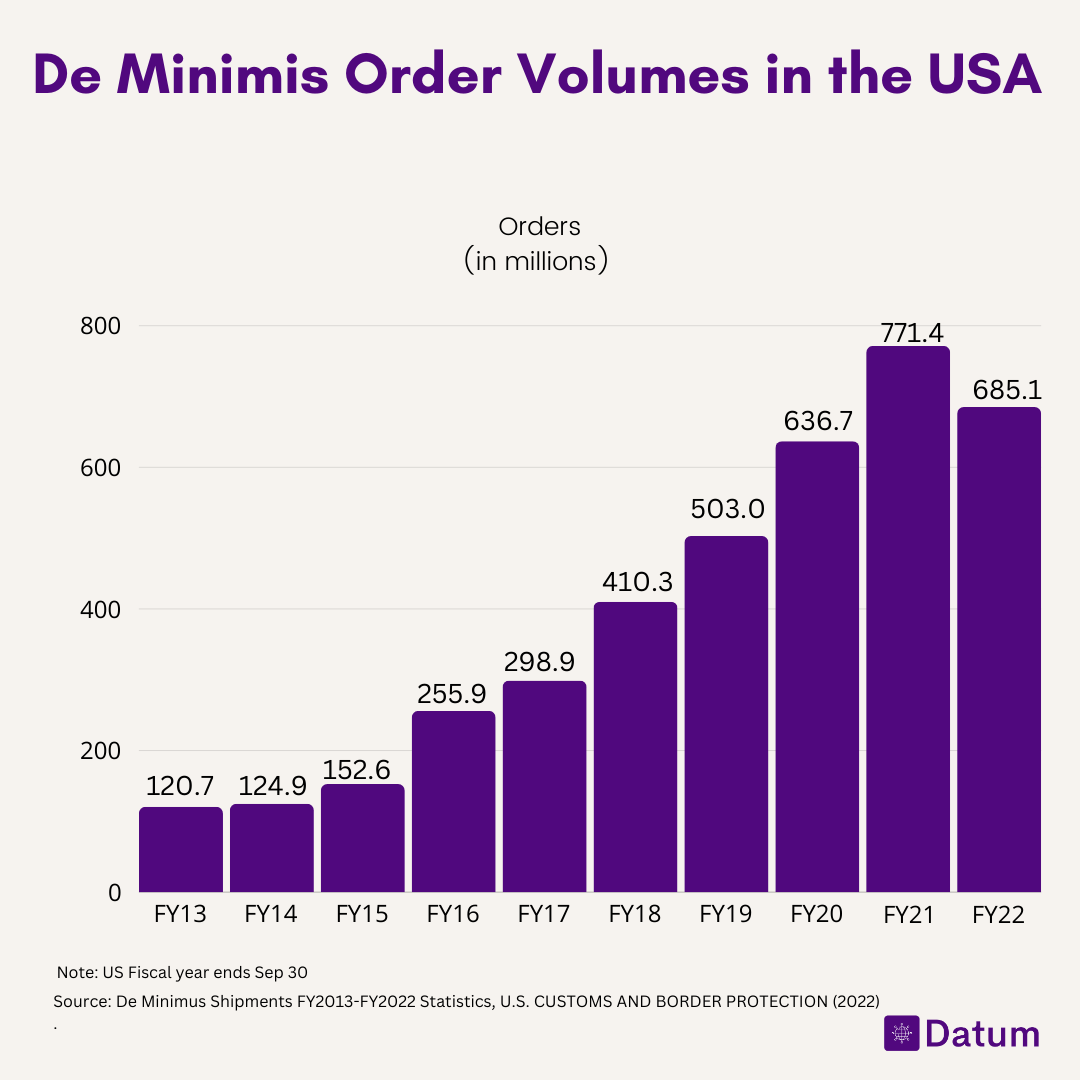

As a student studying sustainable fashion, a company’s sourcing habits greatly affect my purchase intention. I buy most clothing secondhand because I do not trust many popular retailers to put sustainability over profit. I will not shop from them if I cannot verify that a brand’s sourcing strategies do not harm people or the planet. Because so many brands are not transparent enough, it is nearly impossible to verify that their sourcing practices do less harm than good. For example, I will not buy from Shein because I cannot verify that their products are made without forced labor. Shein, among many other Chinese fast fashion retailers, takes advantage of de minimis policies, which allow many product shipments to sneak through customs. There is a possibility that Shein sources cotton from the Xinjiang region of China, so I do not shop there.

Kendall Ludwig, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

A fashion company’s sourcing sustainability efforts are a huge determinant of whether or not I will buy from them. This is one of the main reasons why I predominantly shop secondhand. Not enough brands live up to my expectations when it comes to supply chain transparency. It is hard for me to buy a new product when I am unsure of where it has been through every stage of its development. Although this is also the case when I buy secondhand clothing as well, I know that I am not directly giving my money to a brand that may be exploiting workers or causing detrimental harm to the environment.

Leah Marsh, Graduate Student (4+1 program), Fashion and Apparel Studies

As a Gen Z consumer who prioritizes ethical and sustainable fashion, there are a handful of different ways that a company’s sustainability in apparel sourcing affects my purchasing decisions. To begin, I believe that research and transparency is the first step I take in order to understand whether or not I should support a specific brand. It is really important to me for a company’s website, or an article of clothing’s tag to disclose as much information as possible. Key information that stands out to me as a conscious consumer is the country of origin, price, fiber content, and even the care instructions.

With this, if I notice that a company sources its materials from a hazardous region or the original retail price is astronomically low, I definitely think twice about purchasing their products. The biggest dividing factor amongst Gen Z consumers is the fact that some see these extremely low prices and follow through with the purchase due to its economic appeal. On the other hand, some see these prices and immediately question how a product could be produced at such a low price, and refrain from supporting the company.

Annabelle Brame, Fashion Design & Product Innovation Major, Senior

Personally, it holds a great deal on how I purchase. While I am a college student I recognize the dramatic harms of shopping fast fashion, which uses a vast range of unsustainable sourcing practices. That leads me not to want to purchase from brands such as Shein, no matter the cost. However, it is important to recognize my background and education. As a fashion student, I have learned so much about what goes on behind the curtain that the masses don’t. I think it is important to remind ourselves when interacting with other individuals shopping at these places, that they are only seeing the surface level of this information, and while we can’t cause them to fully understand it in one conversation, we have to remember creating resources and alternatives that demonstrate sustainable sourcing is what can help make that difference.

Also we have to consider the trade-off. Can we stop purchasing from companies who aren’t making changes in how they source? Not always. So, we have to think critically about how we consume and show ourselves grace as we work towards a more sustainable future. Is it possible to quit shopping at brands that do not pay their workers a living wage cold-turkey?

Honestly, probably not. Many of our brands are not transparent or know fully what is happening where they are producing so it is extremely difficult as consumers to buy into the right places correctly. Also, the key is moderation, just like going on a diet. If you give up all sweets, it makes it more likely you will quit the diet altogether. But what will lead to your success is learning how to consume it in a healthy moderation. For example, instead of spending hundreds of dollars on hauls of clothing, consume less. A purchase every now and again is nothing to feel guilty of. It is all about moderation. The ways these unsustainable companies make their money is from the mass amounts of consumption. By consuming less, it significantly begins to help the problem. That is what I think scares Gen Z so much, the idea that it is an all-or-nothing trade when purchasing.

Hunter Wills, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

A company’s sustainability in apparel sourcing is the main driver in my purchasing decisions. This makes it very hard for me to justify buying anything new because there are very few brands that are making clothing with sustainable sourcing in mind and are offered at a price point that I can afford. This usually causes me to look online or thrift stores for second-hand clothing that I know will last.

Are there specific sustainable materials or practices in apparel sourcing that particularly interest you and your peers? Why do you find them appealing or important?

Cecilia Goetz, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors), Senior

The act of recycling fabrics to create new textiles or upcycling old garments into exciting and fashionable pieces is a practice that definitely resonates with several members of Generation Z, including my peers and me. Overproduction and overconsumption are two very large issues in the apparel industry that have an extremely negative effect on the environment…Upcycling, in particular, is something that Gen Z has taken a liking to. My Tik Tok “for you page” is often filled with crafty teenagers turning a worn down pair of pants from Goodwill that they would never wear into a stylish two-piece set that can be worn in multiple ways. Not only did they spend little money, but they also got the opportunity to show off their creativity and design skills on an app that could allow them to go viral at any moment. In posting these videos, they are helping their personal brands while showing their viewers how they can be sustainable and upcycle clothing themselves.

Emilie Delaye, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

The biggest sustainable materials and practices that come to mind would probably be associated with the key terms “organic cotton” and “fair labor”. In terms of sustainable materials, organic cotton has become one that is very popular in Gen Z, and one that brands have quickly picked up on and highlighted in their practices. The other term that I believe highlights some of the most popular practices when it comes to sustainable sourcing is fair labor. This practice I believe is still particularly prevalent in the more “woke” crowds of consumers, however has begun to penetrate mainstream discussion. I believe that Gen Z consumers want to be able to consume clothing, knowing that the production and sourcing was not associated with child or slave labor. Brands have also tended to emphasize this practice for their consumers. Whether their statements are an accurate representation of their sourcing has yet to be seen.

Hannah Laurits, Graduate Student, Fashion and Apparel Studies

Absolutely! Specific materials are very appealing to both myself and my peers. Any time I come across an article of clothing, one of the first things I do is to inspect the inside tags to determine its place of origin and the fiber composition of the fabric. Investigating a product’s origins provides valuable insights into that garment’s potential economic and social impact.

What excites me the most are sustainable fibers, especially new innovations which are more environmentally friendly. When looking at fabrics, I watch for green flags such as organic fibers, hemp, linen, bamboo, and more. Many of my peers are interested in recycled fibers, such as recycled cotton. These fibers are enticing to my peers and I as they are much less harmful to the environment compared to other alternatives.

Miranda Rack, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors) & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

Sustainable apparel sourcing does not just include supply chain transparency but also the environmental impact of sourcing decisions. Brands often set benchmarks to reduce carbon or water emissions, use more recycled textiles, source only organic materials like cotton, or no longer use animal fur. All these issues are equally important in sustainability, but consumers will prioritize issues that personally interest them when shopping. Personally, I am most passionate about overconsumption and post-consumer textile waste. So, I am more likely to shop at secondhand stores than slow fashion retailers.

Kendall Ludwig, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

I think organic cotton has become quite popular recently with our peers. In the Sustainable Fashion Club (note: a student organization at the University of Delaware), the most popular activity by far is painting organic cotton tote bags. Our members love receiving a product that was made with sustainability in mind. While there are unsustainable elements to organic cotton, it seems to be what our Gen Z peers are most drawn to when trying to consume with intention. I think this is still a step in the right direction because consumers are becoming more informed about sustainability in fashion if they are drawn to organic materials. As their knowledge increases, so will responsible purchasing decisions.

Leah Marsh, Graduate Student (4+1 program), Fashion and Apparel Studies

I believe that the sustainable practice in apparel sourcing that resonates with me the most is ethical labor. The topic of fair treatment and fair wages for workers in the fashion industry is what first got me interested in sustainability as a whole. It is extremely important to ensure that all workers are paid fairly, provided safe working conditions, and have basic labor rights protected. There are a handful of accounts and campaigns on social media that introduced me to this important issue. I follow Labour Behind the Label and Fashion Revolution which are two of the non-profit organizations that advocate for a more ethical and sustainable supply chain. Moreover, two of the most prominent social media campaigns are the #PayUp movement and the #WhoMadeMyClothes movement.

Annabelle Brame, Fashion Design & Product Innovation Major, Senior

As a designer, I have really gravitated to fabrics that are not blends. That allows for fabric to be easily recycled after the product’s life, unlike blended fabrics. Secondly, brands sourcing from the U.S. because I feel confident in our enforcement of labor laws. Being able to have the transparency from just trusting the government policies is comforting and inspires me to want to support businesses that run their brands like that. As other countries begin to make changes in their laws, it opens my mind to implementing sustainable sourcing internationally.

Also transparency. I would rather have a company tell me they pay their worker $68 a month than tell me nothing at all or try to make themselves look better than they are. Having that information allows me to evaluate in my brain, if this is ethically right for me. In doing so, it allows consumers to encourage change.

Hunter Wills, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

One sustainable practice that I resonate strongly with is upcycling. Upcycling is taking pre-existing clothing and using it to make new garments. I currently do this with my clothing brand named Funky Rat, where we take older pieces of clothing and add our own designs via embroidery and screen printing to them and then sell them. We could have started the brand by having a completely custom hoodie manufactured for us, but we felt there was no need to have this new garment made when we can find perfectly good quality hoodies at local thrift stores and design on top of these. This also allows us to have a unique selection of products and colors, as opposed to having 50 of the same exact thing.

Another practice that resonates strongly with me and my peers is zero waste design. Last semester I found this concept for the first time and was immediately intrigued. I ended up making a hoodie shortly after using a zero waste pattern from the designers Shelly Xu and Katla. It was incredible to me to see something so simple in terms of a pattern fit so well, while creating no waste. I am currently working with a friend on a few zero waste patterns and design concepts, and I cannot wait to see where this concept moves in the future, especially at scale.

How effectively do fashion companies communicate their sustainability efforts to Generation Z like yourself? Are you concerned about the issue of ‘greenwashing’?”

Cecilia Goetz, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors), Senior

There is definitely some “greenwashing” and performative language used by fashion companies. Some brands struggle to include every detail of the processes that go into the manufacturing of their products. Although they are rarely lying, they often word things in a way that makes them sound better than they are while excluding important information. Some companies are known for their recent shift towards more sustainable practices and transparency. However, they still fail to include exact information about their factory set-ups and are often called out for their lack of true transparency. Moving towards sustainability in the apparel industry has become a major trend in recent years and I think brands are more-so trying to appease consumers and maintain a certain image of integrity, rather than make genuine changes in their mindsets and overall brand ideals.

The main issue behind greenwashing– besides the fact that it is somewhat unethical and sly– is that it works. Because so many customers are unaware of the lack of social responsibility and environmental practices within apparel production, they have no reason to believe that a brand might be withholding some of the truth on the tag of a garment or the product description online. They instead are excited by the thought of a “sustainable” piece of clothing and are often more inclined to actually follow through with the purchase. I will, however, give Generation Z some credit. I think my age group definitely cares more about sustainability than older generations and would be more likely to notice cases of greenwashing than other consumers.

Emilie Delaye, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

I think that greenwashing is a major issue in the industry today. Brands have become more astute and turned into what consumers, such as Gen Z consumers, want and, therefore, have amplified their messages on sustainability and ethical business practices extensively. If you look at even major fast fashion brands, such as Shein, it can be seen that the term “sustainable” is thrown around quite frequently, with very little information to back up the statements. I do think as I have said, however, we are not at the point yet where the majority of Gen Z consumers question the words of the brands they are buying from. If a consumer sees that a brand has a section on its website that is dedicated to sustainability, they are very likely to believe that this brand is infact, sustainable.

Hannah Laurits, Graduate Student, Fashion and Apparel Studies

Honestly, it’s really hard right now for fashion companies to communicate their sustainability efforts to Generation Z, this is because sustainability is such a hot topic. Virtually every brand strives to align itself or its products with sustainability, even when its practices do not genuinely reflect these values. Greenwashing is a deceptive marketing tactic and is a large concern for my generation. As consumers and future industry professionals, we are very much aware and mindful of greenwashing practices.

In the retail setting, when I encounter multiple tags flaunting recycled symbols, excessive claims of environmental friendliness, or any other indications of greenwashing, I am immediately deterred. The best thing that a company can do to communicate sustainability efforts to Generation Z is to do so in a subtle yet thoughtful and thorough way. For example, I look for companies that have a dedicated page on their website that goes in depth about their sustainability efforts and future goals. Levi’s is a great example of a brand that does this well.

Brands that genuinely pride themselves on being sustainable and prioritize sustainable practices, should convey their efforts without resorting to overt marketing tactics which may resemble greenwashing. Instead, they should lead with authenticity and transparency, fostering Generation Z’s trust and loyalty as consumers committed to sustainable lifestyles.

Miranda Rack, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors) & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

Fast fashion companies do a horrible job communicating their sustainability efforts to Generation Z. The “sustainability” tab is always super small, all the way at the bottom of the home page. Fast fashion retailers are not forthcoming about sustainability initiatives because there is almost always nothing to brag about. I am very concerned about greenwashing because it is just another way for brands to take advantage of consumers. Most consumers do not study sustainable fashion, so when they read “made with 80% recycled fibers,” they believe it is true without verifying. Most brands do not outright lie about their sustainability efforts, but they do hide how their products and practices are killing the planet. Overconsumption is an enormous issue that is hidden from the public because so much post-consumer textile waste is shipped overseas to developing countries. Countries like Ghana and Chile are drowning in our old clothing, but Shein shoppers know nothing about this issue because it is not communicated to consumers.

Kendall Ludwig, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

Greenwashing is a huge concern as sustainability continues to be identified as a “trend” that brands need to keep up with. Sustainability is not a trend. As a fashion student focusing on sustainability, it is easy for me to identify greenwashing tactics, especially on a brand’s website. But for consumers unfamiliar with greenwashing and sustainability efforts, they may see a sustainability page on a brand’s website and think the brand is doing their part.

Leah Marsh, Graduate Student (4+1 program), Fashion and Apparel Studies

Since sustainability and ethical fashion have become such a hot topic within the industry, I believe that fashion companies have been extremely successful in communicating their sustainability efforts to Gen Z. Companies are aware that this is currently the top priority for my generation, and they are definitely marketing towards it. For example, fashion brands such as H&M have not only increased the information they provide on individual products, but they have also added an entirely new tab to their website dedicated to sustainability. The new tab allows customers to explore the company’s work and commitment to sustainability. However, this has also raised the concern of “greenwashing.” Greenwashing is when a company claims to be doing something to improve their effect on the environment, but there is no proof of change or improvements. Consumers wonder how companies like H&M can prioritize sustainability when, at the same time, they are still a global fast fashion company that produces a plethora of products at relatively low prices.

Annabelle Brame, Fashion Design & Product Innovation Major, Senior

Quite honestly, extremely poorly. Off the top of my head, I can think of maybe two larger brands that I feel do an adequate job at showing their customers their efforts, which is so heartbreaking. I see the issues with greenwashing everywhere I go. Unfortunately, I don’t even believe it is fully the company’s fault. They themself are just uneducated on the topic. We do not have enough professionals to guide a change and effectively communicate “sustainability”; instead, we have incredible marketers who know how to influence consumers. As Gen Z wants to shop sustainably, we often settle for what we see, because we want to believe change is being made.

Especially with the idea that sustainability has to be expensive when we see a supposed “eco-conscious” shirt with sustainable materials for a good price, we don’t look into it. For example, organic cotton has so many benefits compared to standard cotton. But many people fail to realize there is just as much, if not more water waste in its creation. And just because that shirt was made with a so-called “better” cotton doesn’t mean workers were fairly treated or the textile mills had negative CO2 emissions. There is so much we don’t look into, partially from lack of time, but also the idea that we can’t fathom being lied to. These companies know that stamping an eco-friendly sticker on the tag does inspire customers, and they take advantage of that.

Hunter Wills, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

I feel that fashion brands do not do a good job of communicating their sustainability efforts to Gen Z. As hard as they try to tell us what they are doing for sustainability, our generation is able to see right through the half hearted efforts and made up terms to fool consumers into thinking they are being sustainable. I feel that this is part of the reason for the resurgence of thrifting, especially with Gen Z. Our generation is tired of being lied to and decided to take that into our own hands with where we buy our clothes from. Thesad truth is that a majority of Gen Z does not know about the impacts of fast fashion and how much of an impact the fashion industry has on the environment. I feel that this is the case because of greenwashing. Brands want consumers to feel that they are helping, not hurting the world with their purchase and will go to great lengths to put on this facade.

As individuals studying fashion merchandising and design and representing the fashion industry’s future professionals, what role do you think your generation can play in advancing sustainability within the industry’s supply chain and sourcing practices?

Cecilia Goetz, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors), Senior

As Generation Z is slowly approaching the title of the “largest consumer group in America,” it is clear that we can play a major role in changing the trajectory of sustainability in the apparel industry. Gen Z’s strong social media presence gives us a type of influence that generations in the past didn’t have. This communication and activism on a worldwide scale allows the group to reach so many different people and create a call-to-action. There are lots of Instagram and Tik Tok accounts like @genzforchange or @environment who aim to educate their followers on current issues and events related to sustainability, social responsibility, and more. With over a million followers collectively, the two accounts can teach young consumers about their impact and how they can change their shopping habits. Adjusting their mindsets from a young age can then change the way they carry themselves as professionals years later and make them more likely to consider sustainability with every decision they make in their jobs. This can, in turn, prevent things like “greenwashing” from occurring because the people behind the scenes are educated on the matter and truly care about advancing sustainability within their companies.

Emilie Delaye, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

I believe that one major role Gen Z individuals studying fashion merchandising and design can play in the industry deals with legislation. Our generation is being educated on these intricate and delicate issues at hand. With the education, we can provide a framework and legal structure that will define what classifies as “sustainable,” and that actively works against greenwashing. Hopefully, we can build a system that ensures brands are backing up their claims and feel the need to act ethically and transparently rather than simply acting in the best interests of their companies.

Hannah Laurits, Graduate Student, Fashion and Apparel Studies

I’m excited to see the increasing presence of Generation Z in the workforce, particularly because we are all so passionate about sustainability. I expect that my generation will play a huge role in advancing sustainability within our industry, supply chain, and sourcing practices as this is an issue that we genuinely care about.

In the years to come, as our generation takes on roles as designers, merchandisers, buyers, and more, we will advocate for sustainable practices within our workplaces. Generation Z has the ability to take this from just a business practice to a mindset for a company. Our generation will push for the adoption of conscious practices across all departments across many fashion brands and retailers. I truly believe that we as a generation, will make a significant contribution to a positive shift in the fashion and apparel industry.

Miranda Rack, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors) & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

Students in the fashion field should be learning about sustainability in their classes. Not only should they be learning about it, but fashion students should also be actively practicing sustainable fashion in their everyday lives. We can take this knowledge to the industry and educate the older generations we will be working with. With sustainable fashion being a relatively new buzzword, we cannot expect all current industry professionals to be as well-versed and subsequently committed. The issue is with education. Consumers still support fast fashion because they are unaware of how it affects people and the planet. The fashion industry must focus on consumer education rather than profit to slow climate change. Educating consumers can start with creating a more transparent and accessible supply chain. Publicizing their supply chain holds brands accountable for using suppliers who uphold their sustainability initiatives.

Kendall Ludwig, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

Our Generation Z is the most environmentally conscious, but at the same time, we buy the most fast fashion products. That being the case, I believe our generation can greatly advance sustainability within the industry’s supply chain and sourcing practices. As avid internet users, raising awareness through social media is one of the most effective and easiest ways to get brands to respond and take action. Gen Z consumers also have the ability to make change through financial means. As the target market for the biggest fast fashion companies, a generation-wide boycott to demand better sustainable sourcing practices would force companies to listen to stay in business.

Leah Marsh, Graduate Student (4+1 program), Fashion and Apparel Studies

I believe that my generation can play a significant role in advancing sustainability within the industry’s supply chain and sourcing practices. I have noticed that a handful of my peers and I have started exploring additional career opportunities rather than being a merchandiser or designer. We have begun to open up doors within the industry and some of the job positions that we are currently seeking did not even exist when we started the fashion program at the University of Delaware just 4 years ago. The increase in availability and demand of these alternative sustainability-related careers within the global fashion and apparel industry is extremely promising. For example, after I graduate, I hope to work for a non-profit organization that advocates for garment workers’ rights and environmental policy while also working to prioritize supply chain transparency amongst fashion brands and retailers.

Annabelle Brame, Fashion Design & Product Innovation Major, Senior

We have the knowledge. As professionals, it is important we just continue to educate others. We will end up all across the globe with people in a million different fields, so it is important to remember not everyone knows what we do, and keep the conversation going. When it comes to sustainability and sustainable sourcing, we have to assume the people around us have no idea what we are talking about and continue to teach and touch on deeper topics within this industry. Also, incorporating sustainability into all our fields. As a fashion designer, it is easy to think we don’t have an impact on how we source. In reality, we can choose fabrics based on fiber, think consciously about the mills, and start conversations in the workplace about how we can pattern-make smarter.

How can education and awareness about sustainable apparel sourcing be improved among Generation Z, both as consumers and as future professionals in the fashion industry

Cecilia Goetz, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors), Senior

Social media is a very powerful tool that can be used to educate Generation Z about sustainable apparel sourcing. Not only can advocates make posts with useful information about sustainability in the fashion industry, but they can get in contact with other members of Gen Z and have meaningful conversations about what can be done to make further progress. This helps to make it a more common discussion and helps to encourage Generation Z customers to keep an eye out for sustainability when shopping.

In the professional world, it is important that companies invest in sustainability initiatives and teams who aim to teach other employees about the subject matter. Those who studied sustainability and related topics can bring this knowledge to the workplace and start workshops, discussion groups, and panels about environmental and social improvements and what every employee can be doing in their role to make improvements. With members of Generation Z focusing on and learning about sustainability from both the production side and consumer side, ethical apparel sourcing is bound to improve in fashion brands around the world.

Emilie Delaye, Entrepreneurship Major, Fashion Management Minor, Senior

One major improvement that I think needs to be done is the focus on how to find reliable information and the skill of critical thinking. Social media and media, in general, have taken over many individuals’ lives today, however, it is known that not all information is true. I think that educating individuals on how to successfully identify whether a source is credible will help reduce the spread of mass misinformation. This, along with the development of critical thinking skills, will ensure that each consumer and professional can create their own opinions on a topic at hand, which in turn will allow our society as a whole to come up with more collaborative and informed decisions on how to tackle the issues we face.

Hannah Laurits, Graduate Student, Fashion and Apparel Studies

Education of sustainable apparel sourcing is extremely important for Generation Z. The best way to improve our generation’s awareness of these issues is by exposing them to real world scenarios and keeping them informed on what is happening in regards to sustainability in the fashion industry. At the University of Delaware, our fashion programs do an excellent job of keeping students informed and engaged with sustainable fashion practices. Sustainability is rooted in the course curriculum in every single fashion class. This is how we improve sustainability awareness in the fashion industry, through consistent exposure, our generation will continue to become the experts in sustainable apparel sourcing.

Miranda Rack, Fashion Merchandising and Management Major (Honors) & FASH 4+1 Program Graduate Student

It is up to brands to be honest with consumers about their apparel sourcing, but it is up to consumers to care. Consumer education and awareness start with transparency by the brand. Generation Z must keep fighting to hold brands accountable. Right now, the best thing consumers can do is to educate themselves on how fast fashion is killing people and the planet. We need to stop shopping at brands that cannot prove to consumers that they value sustainability. We must stop shopping at brands that refuse to publicize their supply chain and sourcing practices. We need to stop taking everything brands say at face value and start working to verify claims on our own terms.

Leah Marsh, Graduate Student (4+1 program), Fashion and Apparel Studies

Education and awareness about sustainable apparel sourcing can be improved among Gen Z by establishing industry standards. Every new sustainable term has a handful of different definitions floating around that ultimately confuse consumers and professionals. There needs to be a standard developed, just like for any other area of study or focus. Consumers need to have something accurate to refer to when they need help making important decisions.

Annabelle Brame, Fashion Design & Product Innovation Major, Senior

As cliche as it may seem, social media. It has an astounding amount of power over our peers and can reach large audiences rapidly. One of the really amazing things that has come from platforms like Tiktok is allowing us to share information creatively. We don’t have to just look at a camera and talk about sourcing, but we can create engaging videos with editing to keep the viewer watching. With so many niches, people can gain a platform that allows them to continue telling the story about sustainability in between feeds of crafts, dancing, and comedy. It allows it to be a recurring reminder between their other programming. That is the key, repetition. It takes persistence from people to grasp the gravity of the issues we face within sustainable apparel sourcing. So it takes us showing up– on the news, social media, and in person.

–END–