- Speaker: Katherine Tai (U.S. Trade Representative, Office of the U.S. Trade Representative)

- Presider: Michael Froman (President, Council on Foreign Relations; Former U.S. Trade Representative, 2013-17)

Excerpt from the conversation

Worker-Centric US trade policy

Question from FROMAN: “Back in the old days, there was a notion that since the U.S. market is relatively open—we don’t have that much protection here, the average applied tariff is about 3 ½ percent—that if we were able to reduce barriers to other countries disproportionately we could export more made by U.S. workers, and that export-related jobs paid more than non-export related jobs, and that we could use access to our market as a way of getting other countries to reform their labor practices and raise their standards, which would create a more level playing field. That theory is sort of out of vogue at the moment. But, tell me, can you envisage what an agreement that is worker-centric looks like that reduces barriers or increases trade?”

Response from TAI: “The percentage of (U.S.) exports to GDP is around 10 percent—maybe 11 or 12 percent. So it’s not very high. Some of our—some of our trading partners have very, very high exports as a proportion of GDP (e.g., 25 percent)…So you just have to put that (trade liberalization) into context. I think you also have to think about the fact of the balance of exports and imports…”

“We’re trying to create and maintain jobs, and good jobs, at home… so then the question becomes not what do I have to pay you to do X, Y, or Z, but how can we put the forces of our cooperation together? What does the deal look like where we are building our middle classes together? And I think that the worker pieces then come in, along with the environment pieces, as something that I shouldn’t have to pay you to do, but as something that you should want to do…”

“Traditionally we’ve kept our scorecard by, you know, how many trade agreements you finished and how many you’ve gotten across the finish line… Our progress lies very much in how the conversation has fundamentally shifted. That the conversation now is very much focused on supply chain resilience, on equity, and how not to leave those within our economies behind further, how not to leave those developing countries behind further.”

Digital trade

Question from FROMAN: “For a long time, the U.S. had a position around the free flow of data across borders, not taxing digital products across borders… given the fact that the U.S. economy is probably—certainly the leader in all things digital, what does it mean for us to move away from defending these principles that have been so core to what we’ve tried to do before?”

Response from TAI: “So in early 2000s that we’re negotiating (digital trade)… It’s called the e-commerce chapter. And it’s the e-commerce chapter in several iterations of FTAs (free trade agreements)…And I think that that makes sense if you think about what the digital economy looked like in the early 2000s. It really was about e-commerce…At the time—thought about e-commerce digital trade provisions as largely facilitative provisions. The flow of data was there, and we wanted to safeguard the flow of data to facilitate traditional trade transactions, the movement of goods across borders, the analogy to services we used also in digital.”

“In 2024, one of the things that you realize is that the flow of data, the decisions around where data needs to be stored, how it needs to be handled, has—on much, much different dimensions because over this period of time, in fact, in the digital economy the data is no longer just about facilitating traditional types of transactions. The data has become the commodity in and of itself. The data is now what has value. The ability to accumulate that data and for vast amounts of data then to be combined with computing power to create things like generative AI and large language models, it starts to give you a sense, just as a normal trade negotiator, that there are much, much bigger equities at stake in what we might be doing in our trade negotiations…It’s not just about facilitating trade, but around how we regulate data and how we regulate the companies that accumulate, harvest, and trade in this data is something that we need to resolve and advance before we can thoughtfully and responsibly engage in trade negotiations to figure out what the limits are in terms of what we should be doing, and what the goals are for what we should be doing with our trading partners… what underlies the digital economy and our digital existences, and just thinking about what the rules should be for how that data is handled, who has rights to that data, and then the international components around trade and prosperity but also trade and national security.”

Tradeoffs in trade policy

Question from FROMAN: “Trade is a great area to talk about tradeoffs. We hate being overly dependent on China for basic goods. We also hate inflation and higher cost of living. The actions taken to deal with the first one will likely exacerbate the second one… How do you talk about that tradeoff with communities around the country? And do you make explicit that, yes, you’re going to pay more at Walmart for this for that, but we’re going to become less dependent on China as a result?”

Response from TAI: “That today, we know that we have critical dependencies and vulnerabilities that are actually bad from a national security and just a geopolitical standpoint. For every sector where we feel that we are critically vulnerable to another country and, say, China in particular, I think that it creates a sense of angst and insecurity that is destabilizing for the world economy and, frankly, for the world… if you look at it from a more holistic, medium-term perspective, supply chain diversity and supply chain resilience is actually a management tool for inflation… “

“For as long as there are concentrated pockets for production and supply—and this is internationally, but this is also the logic behind taking on dominant players in our economy—for as long as you have that kind of dominance, you’re going to have in the hands of certain players the ability to distort the market and to take advantage of that dominance by jacking up prices, whether it’s shrinkflation, or greedflation, or in the international context economic coercion… if you think about the tradeoff as between today and tomorrow, it’s not zero-sum at all. And in fact, these changes are ones that we need to be able to manage, not being faced with the same risks over and over and over again.”

US trading partners

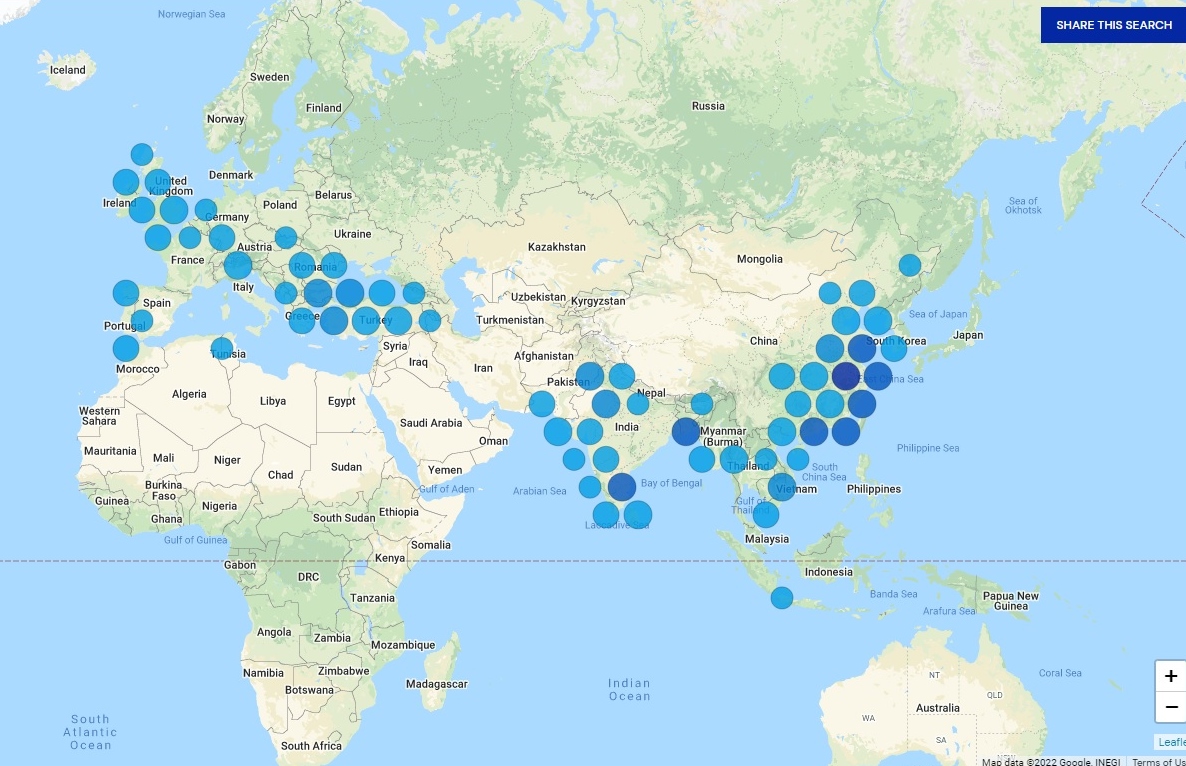

Comment from TAI: “when you talk about some evolution in our (trade policy) approach, I just want to be clear, the evolution in our approach is about what should be in those things, what should be in those agreements, what should be in the exercises and the cooperation that we undertake with our partners. This is not a walking away from those partners, at all…You’ll see how much time I spend in Brussels, how much time I’ve spent in Asia, and the Indo-Pacific over the course of the last three years. And you’ll see that the prioritization of our like-minded partners, our traditional partners if you will, is still very much there.”

Tariffs

Comment from TAI: “What is really important to appreciate about tariffs is that they’re a tool. They’re a tool that can be used in constructive ways… They’re a tool, at least for us, in trade remedies… They are a tool for remedying unfair trade. I actually kind of like the way the Europeans describe these types of tools—dumping, countervail. They call them trade defense instruments.”

“What I also want to reflect is that trade policy and economic policy isn’t just tariffs… we have kept a lot of the tariffs, because we see strategic value in those tariffs in this exercise of building up the middle class and reinvigorating American manufacturing and the American economy… it needs to take the tariffs as a tool, the investments as another tool to help reinforce, policies that support and empower all workers, and to encourage our partners to be supporting and empowering their workers, and then also promoting economic vitality, opportunity through the enforcement of our competition laws…”

Textile industry strategic or not?

Comment from TAI: “You know, there are things that are more strategic, things that maybe we feel like are less strategic or not strategic. But, you know, I think that is actually a really, really important question. And it’s a hard one—what’s strategic and what isn’t? We clearly did not think that surgical masks—surgical, you know, medical-grade gloves and ventilators were that strategic. And so we let that go wherever it was going to go. And in the early days of the pandemic, boy, did that hurt us a lot. So, you know, one of the—one of the stories that came out of the pandemic was all of our—all of our textile manufacturers, you know, were told your industry is not that strategic. They’d been told it for a long time. And yet, we know that it is important. It’s politically important. And USTR has for a very long time had a textiles office and textiles negotiator…it was that textiles industry, what we still have, that was able to repurpose their capabilities and to step up, and to actually start producing some of these things that we were really deficient in during the pandemic, and to save us. So I think that where you draw the lines on strategic and nonstrategic… It’s not necessarily obvious.”

Video discussion questions [For students in FASH455, please address at least two of the following questions in your response]

#1: Tai emphasizes the importance of creating and maintaining good jobs at home and building middle classes together with trading partners. How can the textile and apparel trade contribute to the goal?

#2: Reflecting on the textile industry’s response during the pandemic, Tai raises questions about what industries are considered strategic and the implications of such categorizations. How should policymakers determine which industries are strategic, and what criteria should be used in making these decisions?

#3: How has the role of data evolved in trade discussions, and what are the potential challenges in regulating data in international trade agreements? What are the implications of digital trade governance on today’s fashion business?

#4: Tai discusses the strategic importance of supply chain diversity and resilience. How might diversifying supply chains contribute to national security and economic stability, and what are the challenges in achieving this diversification? Please use the textile and apparel sector as an example.

#5: Any other reflections, thoughts, or feedback on the conversation?