ASKET is a prominent online retailer based in Sweden that commits to complete supply chain transparency. Based on analyzing nearly 40 unique products and their detailed supply chain information posted on ASKET’s website as of May 2023, the article aims to shed light on the company’s supply chain traceability progress and the remaining challenges it faces.

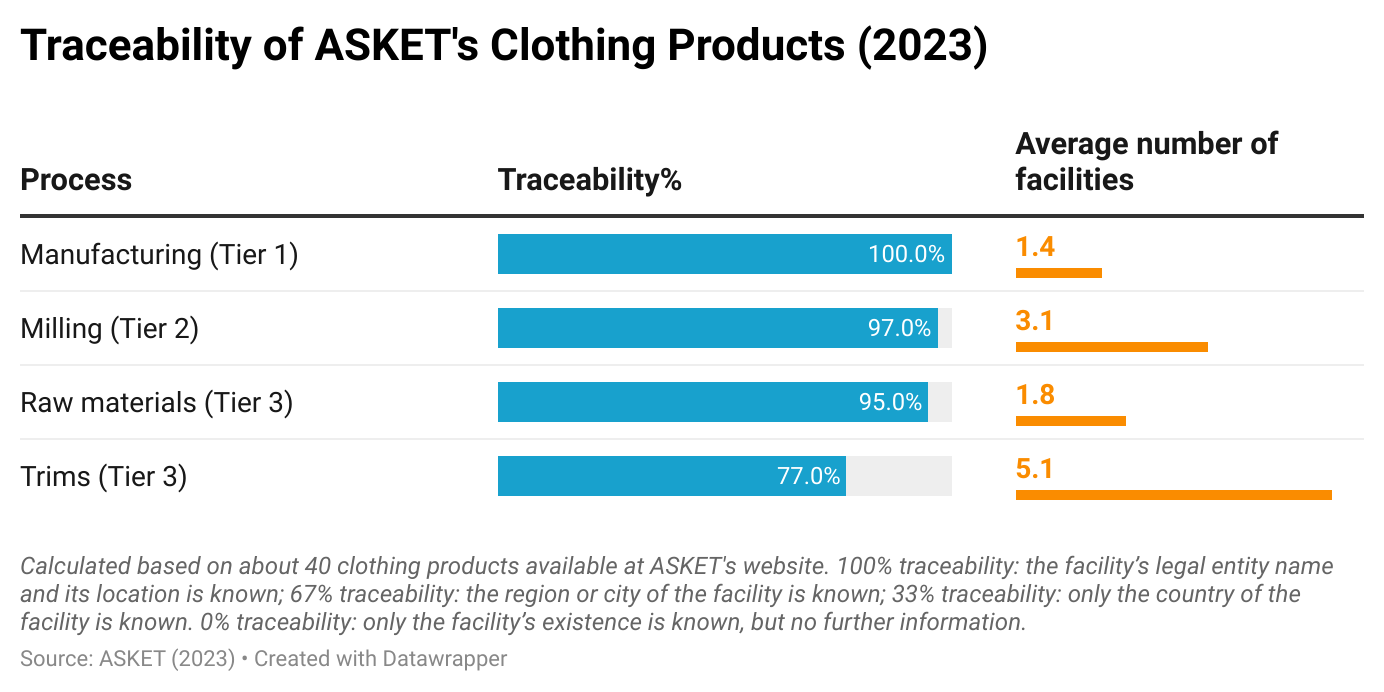

First, while ASKET achieved full traceability for Tier 1 suppliers, tracking Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers was more difficult. For example, compared with its perfect traceability score for Tier 1 suppliers (i.e., garment factories), ASKET’s average traceability for Tier 2 Milling factories (i.e., yarn and fabric producers) was at around 97%, and the score fell to only 77% for trims suppliers in Tier 3.

As one critical contributing factor to the phenomenon, Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers had far more players than Tier 1, which presented a more significant challenge in obtaining detailed information about all the factories involved. For example, ASKET’s garment cutting and sewing operations predominantly occurred within a single facility. In contrast, making yarns, fabrics, and trims EACH usually involve multiple facilities in different parts of the world.

Second, a comprehensive understanding of the sub-supply chains associated with apparel components is pivotal in enhancing a fashion company’s overall traceability. Notably, the apparel supply chain is far more complicated than the commonly known four stages—fiber, yarn, fabric, and garment manufacturing. Rather, apparel components like yarns, fabrics, sewing threads, buttons, and zippers have complex and intricate sub-supply chains. For instance, for ASKET’s shirts or polo shirts:

- Cotton was “farmed in New Mexico, Arizona, California and Texas, USA, ginned in Anqing, China.”

- Yarn was “spun and twisted in Hyderabad, India,” and “dyed in Varese, Italy.”

- Fabric was “woven in Letohrad, Czech Republic, dyed and finished in Prato, Italy.”

- Sewing thread was “produced in Breisgau, Germany, wound and packed in St. Maria de Palautordera, Spain”

- Button was produced in Saccolongon, Italy, with corozo farmed in Manabi, Ecuador.

Third, using recycled textile materials in apparel products could make it trickier to map the supply chain.

- ASKET reported no problem tracking recycled textile materials derived from natural fibers, especially recycled wool products.

- ASKET’s capability of tracing recycled man-made fiber textiles yielded mixed results. For example, ASKET was still investigating the Tier 3 raw material suppliers for one fabric made with “100% pre-consumer recycled nylon.” Likewise, for one body fabric derived from “plastic waste collected from Spanish Mediterranean and French Atlantic oceans and coastlines,” pinpointing the precise origin of the raw fiber posed a challenge.

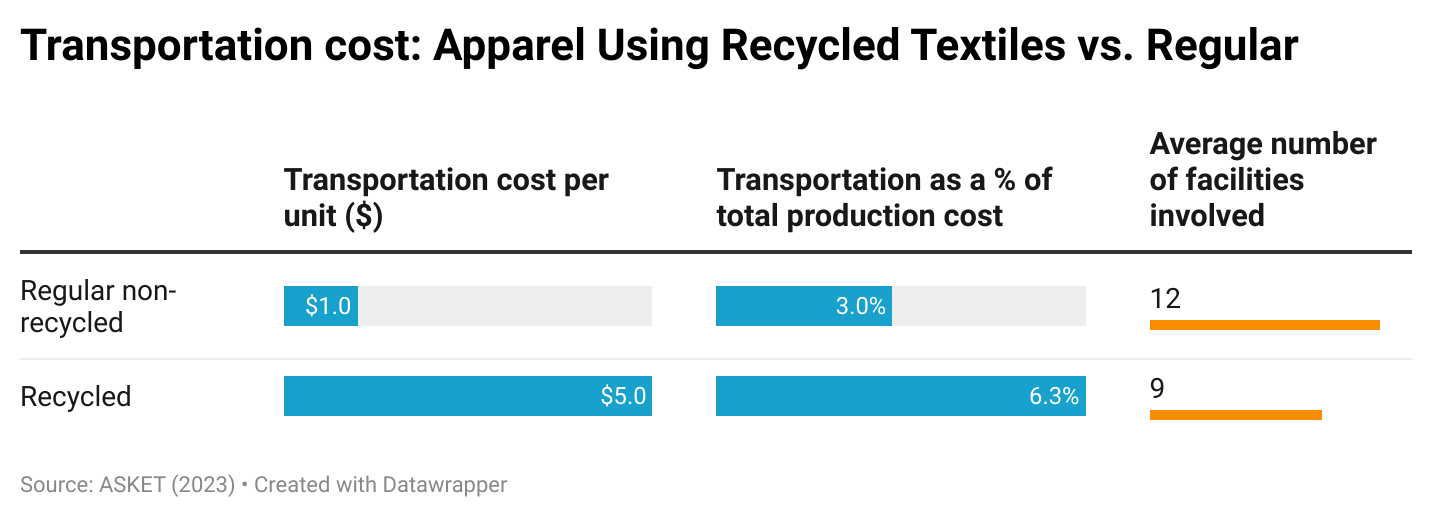

Fourth, ASKET’s data shows that using recycled textiles in apparel products could incur higher transportation costs. For example, the average transportation cost for an ASKET garment using recycled textiles would reach $5 per unit (or 6.3% of the total production costs), much higher than regular clothing using non-recycled materials ($1 per unit or 3% of the total production). However, on average, making a garment using recycled textile materials could involve fewer facilities(e.g., 9 vs. 12). This result suggests that the higher transportation cost associated with clothing made from recycled textiles may not be attributed to a longer supply chain but rather to a more tedious and expensive recycled fiber collection process.

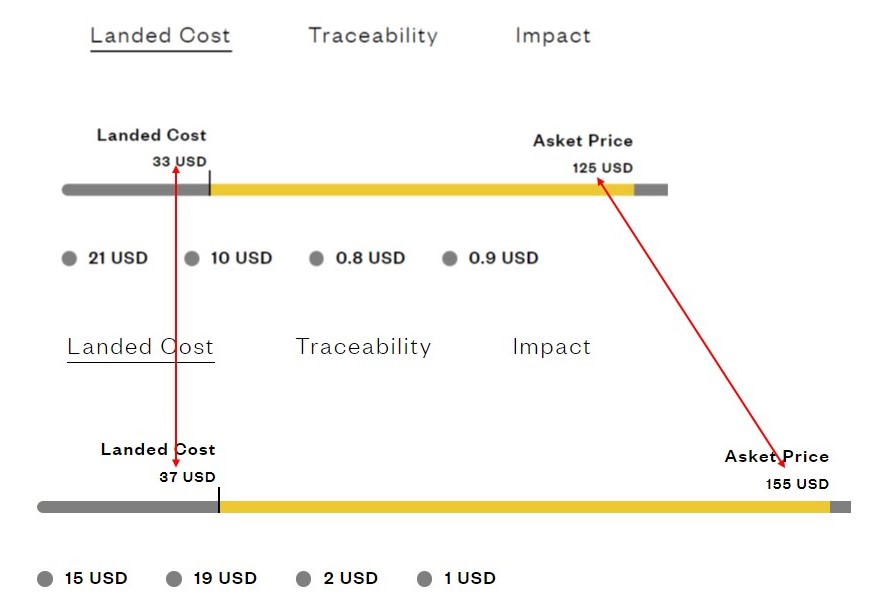

Additionally, ASKET’s data indicates a strong correlation between its retail price and sourcing costs. Specifically, ASKET’s applied a gross margin% ranging from 71%–81%. This implies that a $2 increase in sourcing costs could potentially lead to a retail price increase of $10-$20. Thus, controlling and managing sourcing costs will always be a priority for a fashion company.

By Sheng Lu

Further reading: Lu, Sheng (2023). How Asket is achieving apparel supply chain traceability. Just-Style.

It seems companies are getting better with traceability in tier 1 factories, for example I recently did a project on the French company, Sezane. They are 100% traceable for tier 1, but after that it significantly declines. After tier 1, things get more complicated to trace, but I think holding companies accountable for traceability across all tiers is important.

It is great that ASKET was able to achieve full traceability for Tier 1 suppliers. It is concerning that tracking Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers were more difficult, especially because Tiers 2 and 3 have a lot more players. But that is partially the reason why they are harder to trace. There are numerous stages in the apparel supply chain, way more than the 4 well-known (fiber, yarn, fabric, and garment manufacturing). Using recycled man-made fiber textiles in apparel products makes it harder to find these Tier’s traceability as well.

While having a diverse sourcing strategy is beneficial, it can be more challenging to track all the suppliers. As we see in this article, the more facilities being utilized, the harder it is to account for all aspects of the supply chain. I think full traceability is quite impressive and increasingly important to the consumer. We have seen a shift in the industry of consumers wanting to shop more sustainably which also requires fashion brands to be transparent with the consumer. I think that a lot of fashion brands aren’t able to track their supply chain because of the diversification in their sourcing. I believe all fashion brands should work towards full traceability because it might prevent disaster. As we saw with the Rana Plaza incident, some fashion companies claimed that they were unaware of the conditions in the factories they were doing business with. I think that if these fashion brands take a deeper look into their supply chain and track their suppliers they can be aware of the business they are conducting and evaluate any harm that they may be causing.

Upon reading this article, I enjoyed learning more about supply chain transparency. More specifically, the challenges a diverse supply chain transparency brings to companies. Generally speaking, the tracking of the suppliers is very hard to keep in forced. Also, getting a more in depth understanding of the sub-supply chains was informative. Each country has their main specialty, for example, as we all know the US has a great scale of cotton farms – which is why there is no surprise that ASKET’s shirts/ polo shirts were farmed in the USA (being one location).

After reading this article, I found it fascinating how transparent Asket is with their sourcing of recycled materials and how expensive it costs, as well as being Tier 1 of their traceability. It is very insightful of why the costs are so high due to high transportation costs when sourcing recycled materials, which is $5 per unit, compared to $1 a unit of companies that do not use recycled materials. This shows that their prices increase with the increase in sourcing costs, which is insightful for their consumers to know why sustainable fashion brands are more expensive. I think that fashion brands should consistently keep track of their suppliers and become more transparent like this brand because this will build their consumers trust and is the first step on brands taking accountability for their unsustainable practices.

Hi Nicole. I also found it so compelling to see why sustainable products end up being so expensive. After viewing ASKET’s graphs and charts, it became clear that in order for products to remain sustainable whilst the company maintains a decent profit margin, the products and garments being sold must be expensive. ASKET, while they may be unaware of it, have set a realistic standard for consumers to begin understanding the prices of products that they choose to purchase as well as why they are set at a certain price. I myself appreciate the work that ASKET has done because now I am able to understand why other sustainable brands set their prices as ‘high prices’.

I have found a new place to shop for clothing over H&M. After reading this case study, it was clear to me the differences between big-name brands from Sweden & lesser-known brands from the same location and how each one has tried to modernize into sustainably sourced company. I appreciate how the blog made sure to highlight the Tiers in which ASKET has tried to maintain transparency with their recycled materials as well are show how this correlates to the prices of their clothing. Reading through this also made me realize how hard it is for a company to remain completely transparent. ASKET in the blog post emphasizes how hard is to track a product exactly through every step of the process such as the traceability of recycled man-made fibers since oftentimes they come as a collage of companies that are recorded. While we haven’t yet gone over this topic within our class, I have gone over this concept in another class at UD as well as reported on a similar Tier system and the difficulties that come along with truly tracing each minuscule aspect of the process. Despite all of this, I would like to make sure to emphasize that this, in my personal opinion, is unrealistic for many companies to do. The detail in which ASKET goes into each part of a garment makes sense for their rather small-scale business but for a company such as Nike, this would be extremely difficult if not impossible due to how heavily distributed their manufacturing process is around the world. On top of this, it’s also unlikely any normal consumer would spend hours going through each garment and where it is sourced before deciding to purchase. While I love and appreciate that ASKET does this for their company, I do not find it likely to be reciprocated by any big-name brands.

Reading this article made me think about the importance of supply chain traceability in a new way. I have always felt that supply chain traceability is crucial for new materials, but have never given deep thought into recycled ones. Without doing much research, I came to the conclusion that the impact of recycled materials outweighed the concerns of traceability, but after reading this article and weighing in the discussions from class, It is clear that overlooking traceability can have large negative outcomes. Not knowing the source of recycled materials can result in companies potentially using materials that don’t match their claims. Without verifying the authentic of these environmental claims, responsible sourcing is completely lost, and with that more harm to the environment is possible. While preventing waste is important, establishing a completely traceable supply chain for recycled materials contributes to a more responsible and sustainable circular economy.

I always find it interesting reading about how different companies all over the world are focusing their efforts on sustainability. ASKET has very interesting tactics and pretty successful results in some instances like with their traceability of manufacturing supplier as well as being transparent about the retail price compared to the sourcing costs of a product. One thing that is interesting to me is that recycled materials are always said to be very sustainable and that we should be shifting to use more of these recycled textiles, while these are the hardest and most difficult products to track. They say in the article that there was no problem tracking recycled materials derived from natural fibers, but when it comes to man-made fiber textiles, it is much more difficult. Tracking all parts of the supply chain is obviously challenging due to how many channels are involved but seeing all the different approaches companies use is really so interesting and eye-opening to me of really how much is going on.

This article highlights the immense complexity of tracing a product’s supply chain in detail. Each product involves numerous components, sourced and processed across multiple countries, factories, and by countless employees. For example, the journey of ASKET’s shirts illustrates this. The cotton was farmed in the U.S. (New Mexico, Arizona, California, and Texas) and then ginned in Anqing, China. The yarn was spun and twisted in Hyderabad, India, before being dyed in Varese, Italy. The fabric was woven in Letohrad, Czech Republic, and further dyed and finished in Prato, Italy. Even smaller components, such as the sewing thread, were produced in Breisgau, Germany, and packed in St. Maria de Palautordera, Spain, while the buttons were made in Saccolongo, Italy, from corozo sourced in Manabi, Ecuador. This example underscores the vast, interconnected nature of global supply chains and the challenges in achieving full traceability.