The United States International Trade Commission (USITC) released its new fact-finding report examining the competitiveness of Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, and Pakistan as apparel suppliers to the United States. The study was conducted in 2024 based on input from secondary sources (e.g., trade statistics, public hearings, and desk studies) and fieldwork. Below are summaries of the key findings regarding apparel export competitiveness.

Factors that affect export competitiveness in the global apparel sector

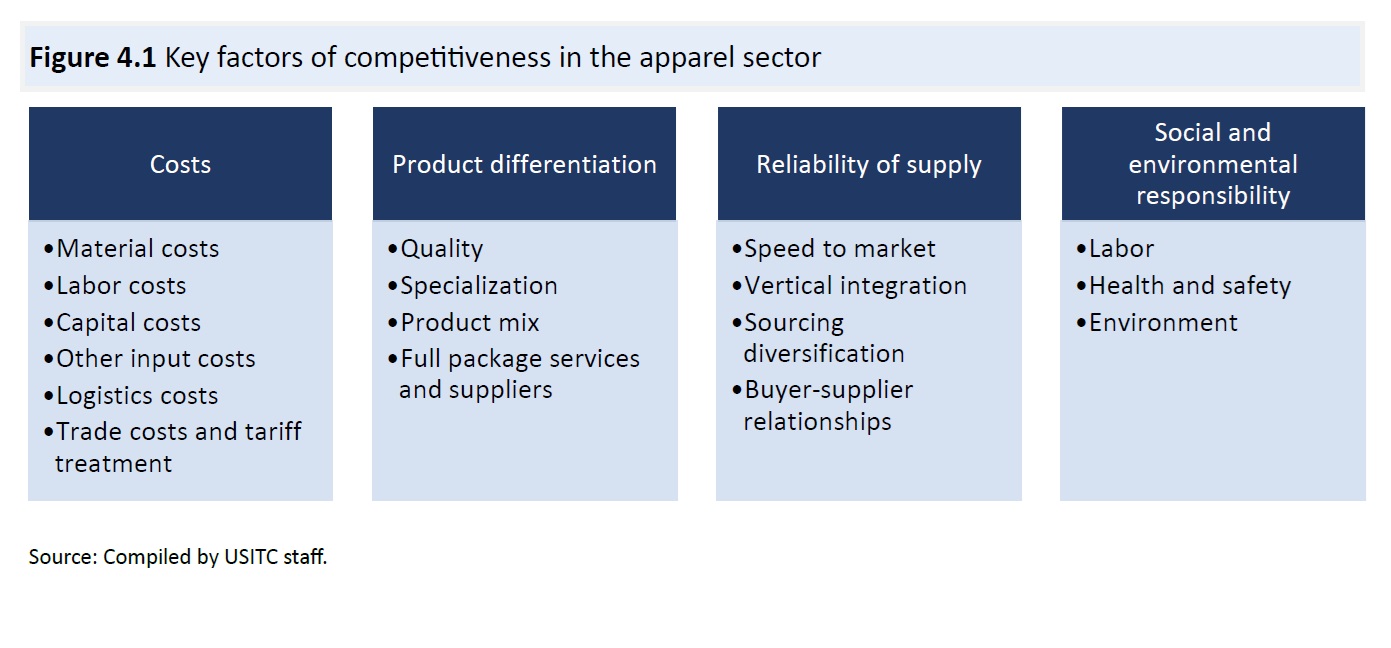

One key issue the study explored is what factors affect a country’s apparel export competitiveness and how to become a preferred apparel sourcing base for U.S. fashion companies.

The studies suggest that four types of factors are most important (see the figure above). However, consistent with existing literature, the USITC report could not determine which factor is decisive in fashion companies’ apparel sourcing decisions. For example, the report found that:

- “cost—the price buyers pay their suppliers—plays a key role in sourcing decisions, although opinions vary regarding the importance of cost relative to other factors.”

- “Depending on the product, target consumer, and identity of a brand or buyer, apparel buyers will place varying degrees of importance on product differentiation factors such as quality, specialization, product mix, and full package offerings, which include design services, finishing, packaging, and logistics.”

- “The emphasis on reliability has particularly grown in response to various recent disruptions to global apparel supply chains such as a global pandemic, geopolitical conflicts, and trade policy.”

- “Although emerging research suggests that compliance programs concerning wages, social inclusion, and climate change mitigation may increase competitiveness, buyers and brands remain divided on the topic…the relative importance, or “weight,” of such compliance in sourcing decisions remains a topic of active study and discussion within the industry.”

Cost and export competitiveness

The USITC report highlighted the complex and nuanced relationship between “costs” and a country’s apparel export competitiveness. Several patterns are noteworthy:

- Apparel is a buyer-driven industry, meaning “the global apparel supply chain gives buyers the power to negotiate based on price, which can push down prices and transfer greater costs to the supplier.”

- The ability to produce textile raw materials locally can provide cost advantages in garment production—“Material inputs are widely recognized as the largest component in the cost of a final apparel product, and these prices are largely determined by the presence of a domestic textile industry or costs of importing textiles.”

- It is difficult to compare wages across countries to measure labor competitiveness. In particular, low labor costs “do not reflect the true cost of doing business (e.g., via wage suppression)” in a country and “they can harm a country’s reputation for social compliance and negatively affect labor productivity.”

Buyer-supplier relationships in apparel sourcing

The USITC report revealed some positive developments in the buyer-supplier relationships involving U.S. fashion companies.

- Fashion companies increasingly recognize the value of building long-term relationships with their vendors. Buyers emphasize that maintaining these relationships is a key factor in sourcing decisions, largely due to the cost and time involved in finding and establishing relationships with new suppliers.

- Fashion companies’ efforts to improve supply chain transparency and traceability also need “suppliers who will act in line with their brand’s values.”

- Suppliers benefit from the long-term relationship, too. As the USITC report noted, some fashion companies guarantee suppliers a particular profit margin to ensure their continued operation. Additionally, some buyers gain a deep understanding of their suppliers’ cost structures, enabling them to calculate the costs of compliance with various standards and assist suppliers in reducing costs where possible.

- Subcontracting is still regarded as necessary for the garment industry. As noted in the USITC report, apparel orders fluctuate seasonally, making it impractical for suppliers to hire additional permanent workers or invest in machinery for peak demand. To meet buyer expectations during busy periods, manufacturers often subcontract parts of orders and increase overtime or rely on temporary contract workers. This practice is seen as essential for ensuring a reliable supply of apparel.

Social and environmental responsibility and apparel sourcing

The USITC report acknowledged the growing importance of social and environmental compliance to a country’s apparel export competitiveness. However, the relationship remains complex.

- The extent to which voluntary social and environmental responsibility programs and their associated auditing practices have influenced outcomes, especially regarding worker rights, remains unclear.

- Suppliers report that the increased frequency of flooding and high temperatures due to climate change negatively affect their ability to meet labor and environmental standards.

- Increased compliance with social and environmental standards raises supplier costs, negatively impacting their cost competitiveness. Many stakeholders note that while brands and consumers demand greater responsibility, this often does not come with a “price premium” for suppliers, who ultimately absorb these increased costs.

Note: The USITC report also evaluated the export competitiveness of each apparel-exporting country it examined, including their respective competitive advantages and issues to address.