This study aims to examine the impacts of the Trump administration’s escalating tariffs on the apparel sourcing and business practices of EU-headquartered fashion companies. Based on data availability, transcripts of the latest earnings call from about 10 leading publicly traded EU fashion companies were collected. These earnings calls, held between August and November 2025, covered company performance in the second quarter of 2025 or later. A thematic analysis of the transcripts was conducted using MAXQDA.

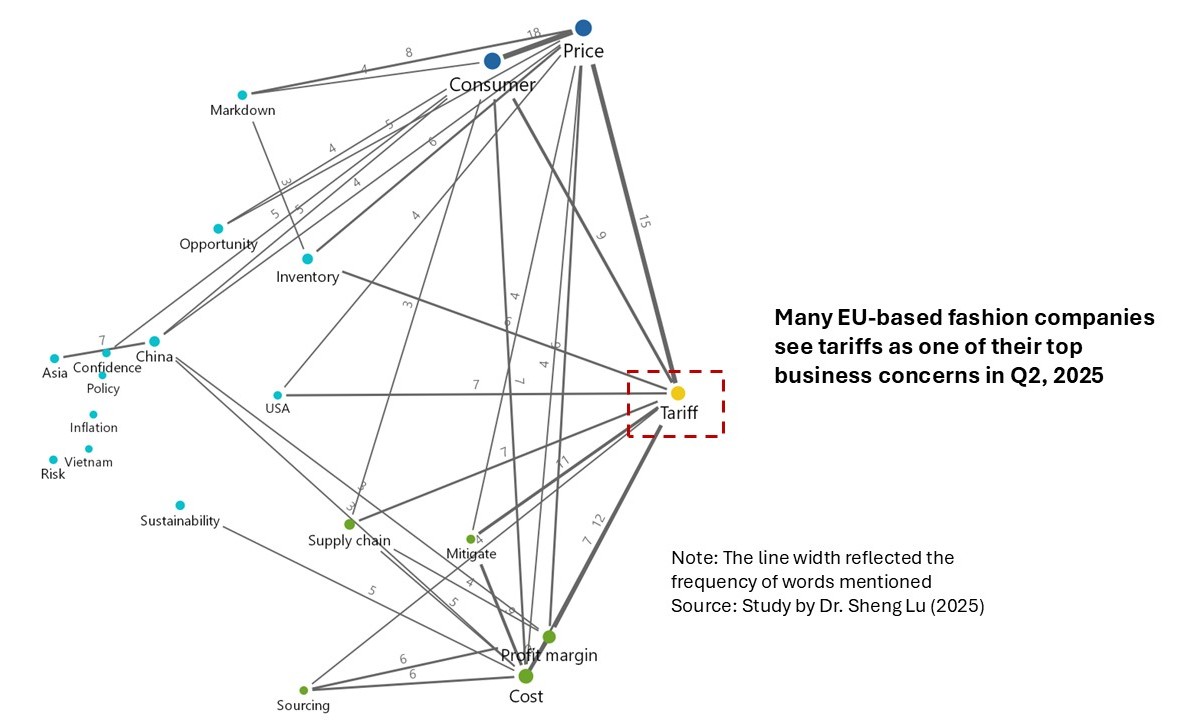

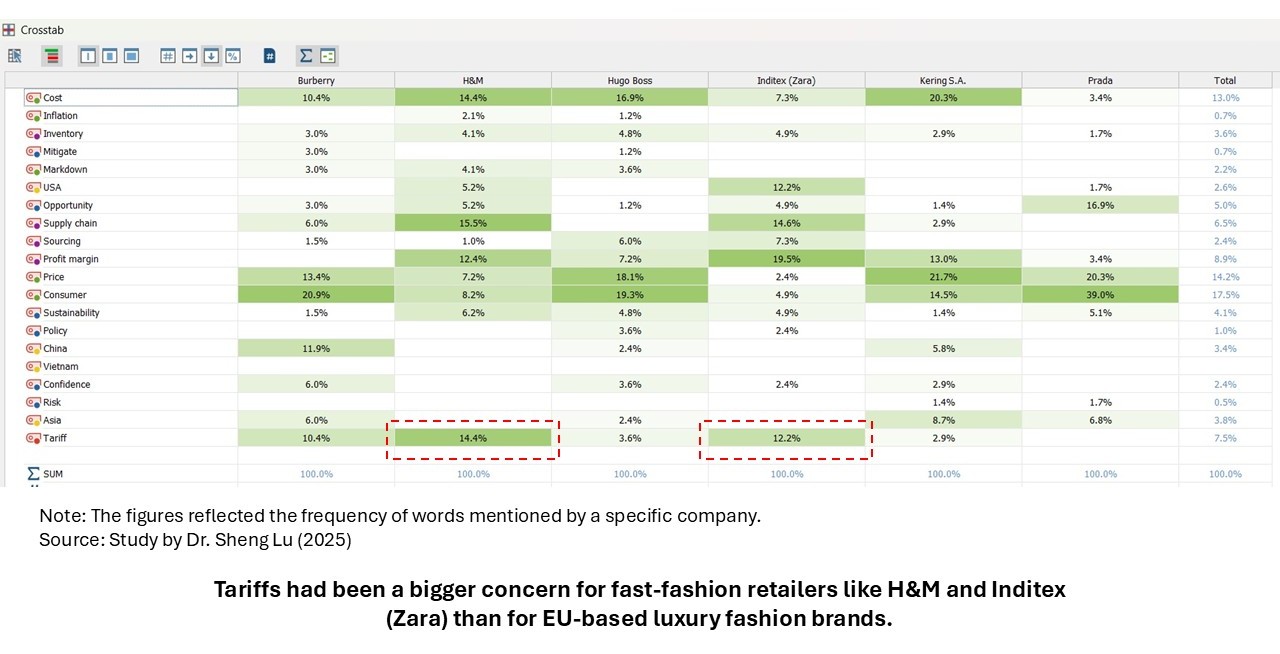

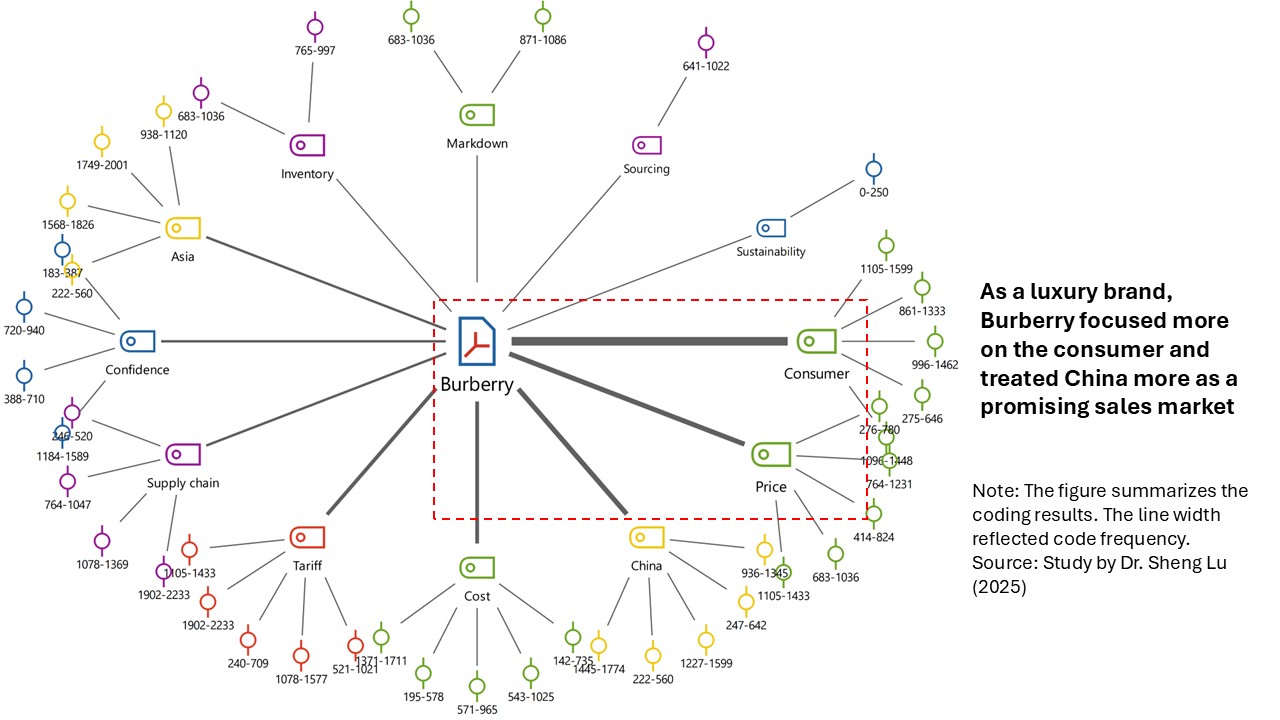

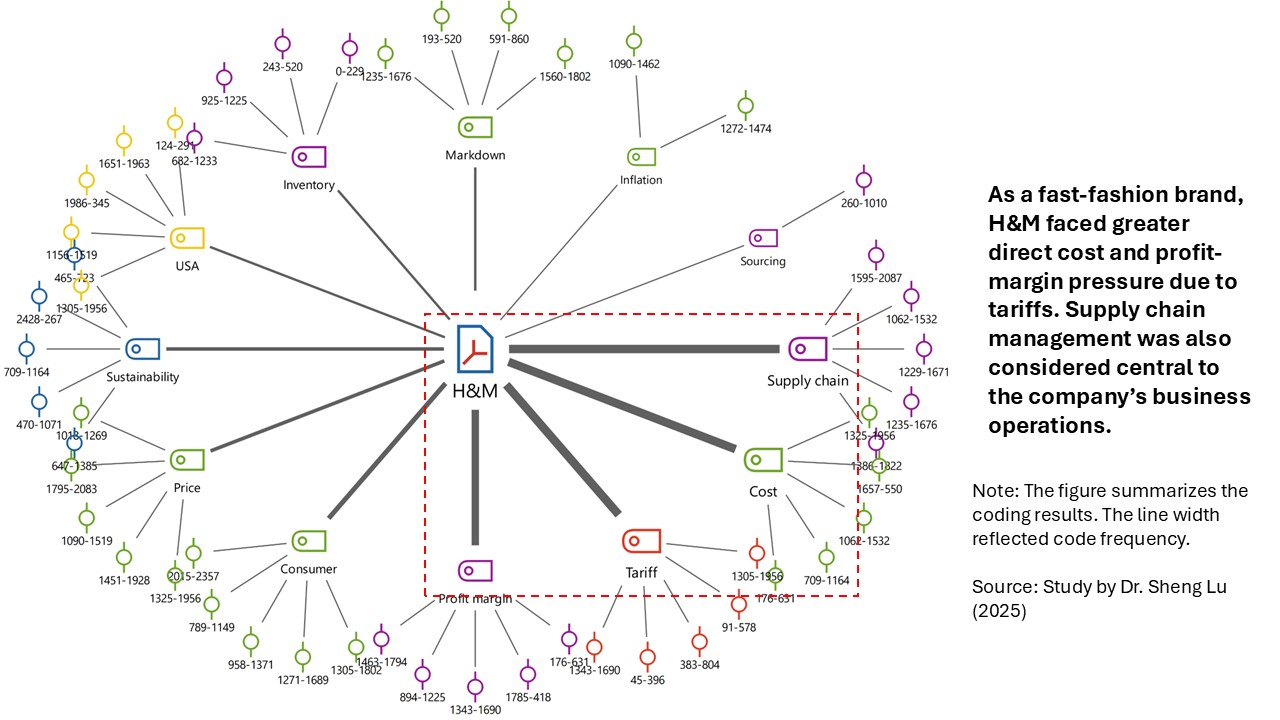

First, reflecting the global nature of today’s fashion apparel industry, many EU-based fashion companies also see tariffs as one of their top business concerns in the second quarter of 2025. However, overall, luxury fashion companies reported less significant tariff effects than fast-fashion retailers and sportswear brands. The result reflected luxury fashion companies’ distinct cost structure, supply chain strategies, and competitive factors, making them less sensitive toward tariff-driven sourcing cost increases.

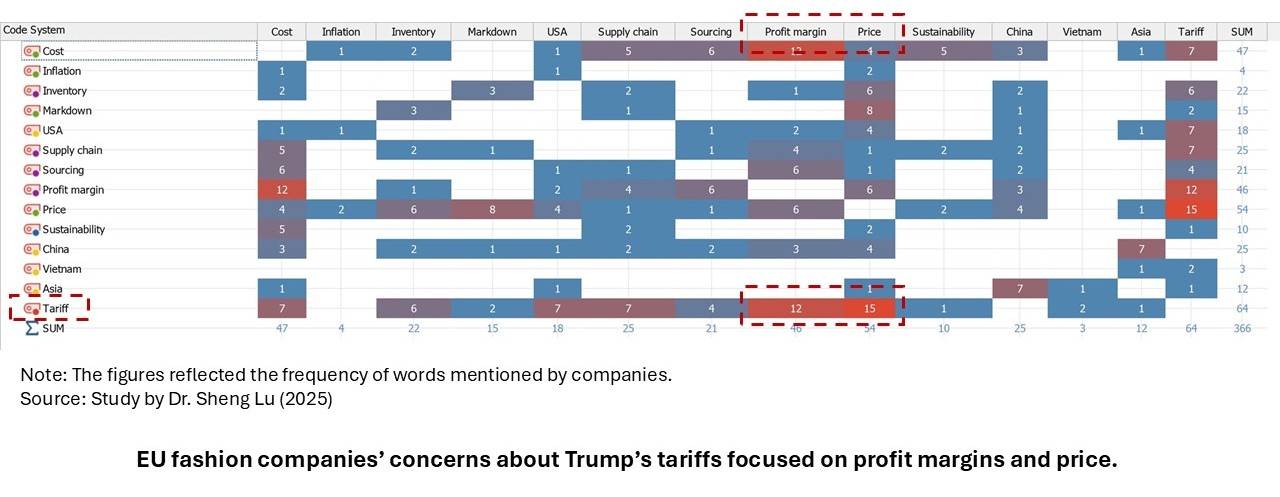

Second, EU-based fashion companies generally regarded the rising sourcing costs and the resulting pressure on profit margins as the most significant impacts of Trump’s tariffs. Companies also noted that the tariffs’ financial impacts would be more noticeable in the coming months as more newly launched products became subject to the higher import duties. For example:

- Adidas: “We already had the double digit hit when it gets to cost of goods sold already in Q2 in the U. S…the impact of these duties, if they are the way we have calculated them here, an increase in cost of goods sold of about CHF 200,000,000 (about $250 million USD).”

- H&M: “Against that, we have the impact of the tariffs that will then, based on the tariffs we pay during Q3, a lot of those garments will be sold during Q4, and that’s when they affect our profit and loss.”

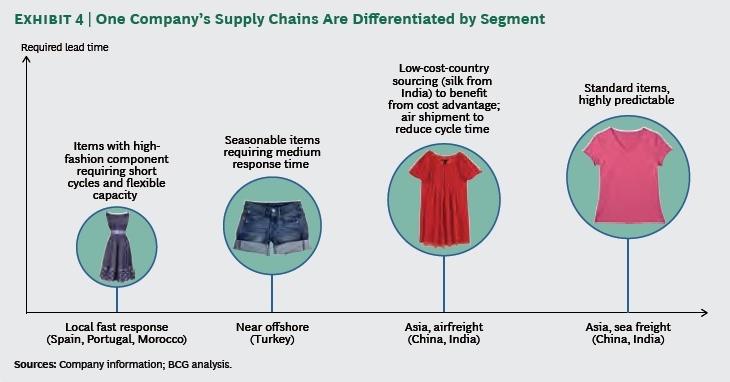

Third, EU-based fashion companies commonly adopted a sourcing diversification strategy to mitigate the tariff impact. Companies also increasingly look for vendors that can deliver speed, flexibility, and agility. Furthermore, some EU companies have been strategically leveraging regional supply chains to meet the sourcing needs. For example:

- Adidas: “We work with our suppliers who are mostly multi country…”

- Hugo Boss: “Since our last update in early May, we have taken concrete steps to mitigate tariff-related impacts. Our well-diversified global sourcing footprint has a clear advantage in this regard. It enables us to swiftly adapt to changing conditions and optimize sourcing decisions.”

- H&M: “We are working on how to increase the speed and reaction time in our supply chain. That’s a wide work that includes both, as we mentioned before, how we move production closer to the customer with what we call nearshoring or proximity sourcing, but it’s also working with a set of suppliers that can be much quicker and where they can support with a larger part of the product development process.”

- C&A: “In the last quarter, we developed our logistics strategy to sustain C&A’s growth curve till 2030…This strategy was designed so as to bring greater speed and flexibility to our operational model through a more regionalized network, that is a network that is closer to the stores and major consumption centers, allowing us to have greater capacity to respond to the demands of each store.”

Fourth, like their U.S. counterparts, some EU fashion companies reduced their “China exposure” to lessen the impact of tariffs. Others establish a “China for China” supply chain due to perceived market opportunities there. For example:

- Puma: “Our China exposure got reduced further for the Spring/Summer 2026 collection…The vast majority of our U. S. Imports originate from Asia, with Vietnam, Cambodia and Indonesia accounting for the majority…”

- Adidas: “China is almost irrelevant for us because we have reduced the amount of China imports into the U. S. to only 2%…What we did is that we transferred the Chinese capacities to be mostly China for China…We have a more verticalized supply chain in China.”

- Hugo Boss: “In particular, we have increased our inventory coverages in the U. S. And successfully rerouted product flows from China to other regions.”

Additionally, despite tariff-driven cost pressures, many EU-based fashion companies were cautious about raising prices, worried about losing customers in an overall weak market. Meanwhile, luxury fashion brands seem more comfortable raising prices than non-luxury brands. For example:

- Adidas: “What kind of price increases could we take depending on the different duties, but there’s no decision on that…We are not the price leader, but we’d, of course, follow, a, what the market is doing, our competitor is doing and also, of course, look very closely what the consumer is accepting because in the end, it’s to keep the balance between all these factors.”

- H&M: “That we do in the U.S., as we do in all other markets, and that leads to both price decreases and price increases to stay competitive. That’s an ongoing work. We are cautious about looking at the Q4 development in the U.S., given that we know we have already paid tariffs that will impact the gross margins as we look into the fourth quarter.”

- Inditex (Zara): “With regards to the tariffs in the U.S. specifically, we have a stable pricing policy that we’re always talking about. Of course, all pricing activity, be it in the U.S. or any other geography, is primarily driven by commercial decisions, not financial ones. What we try to do in every market is maintain our relative position.”

- Burberry: “19% of our revenues are from the US…We spent much of last year looking at the supply chain, looking at price elasticity…We took quite a surgical approach to price increases in the US, and…we really definitely understood where we had price elasticity there.”

- Hugo Boss: “we will introduce moderate price adjustments globally with the upcoming spring 2026 collections, which will begin delivery towards the 2025. These steps aim to safeguard our margin profile while remaining aligned with broader market dynamics.”

by Sheng Lu