The latest US apparel import data raises several puzzles that deserve to be investigated further.

Question 1: Why did imports suddenly surge, and is this surge sustainable?

Unexpectedly, US apparel imports experienced a significant surge in February 2024. This surge was marked by a 12.9% increase in quantity and a 2.9% increase in value compared to the previous year. Seasonally adjusted US apparel imports in February 2024 were also nearly 10% higher than in January 2024. The import surge was particularly surprising given that the value of US clothing sales in February 2024 was only 1.3% higher than a year ago and even 0.5% lower than in January 2024 (seasonally adjusted).

That being said, US total merchandise imports also enjoyed a 2.2% increase year over year in February 2024, the best performance since last fall. Meanwhile, the World Trade Organization (WTO)’s latest April 2024 forecast predicted the world merchandise trade volume to grow by 2.6% in 2024 as opposed to a 1.2% decline in 2023.

Therefore, it will be important to watch whether the US apparel trade has indeed reached a turning point and will continue growing in the coming months and throughout the year.

Question 2: Could the volume of US apparel imports in 2023 have been underreported?

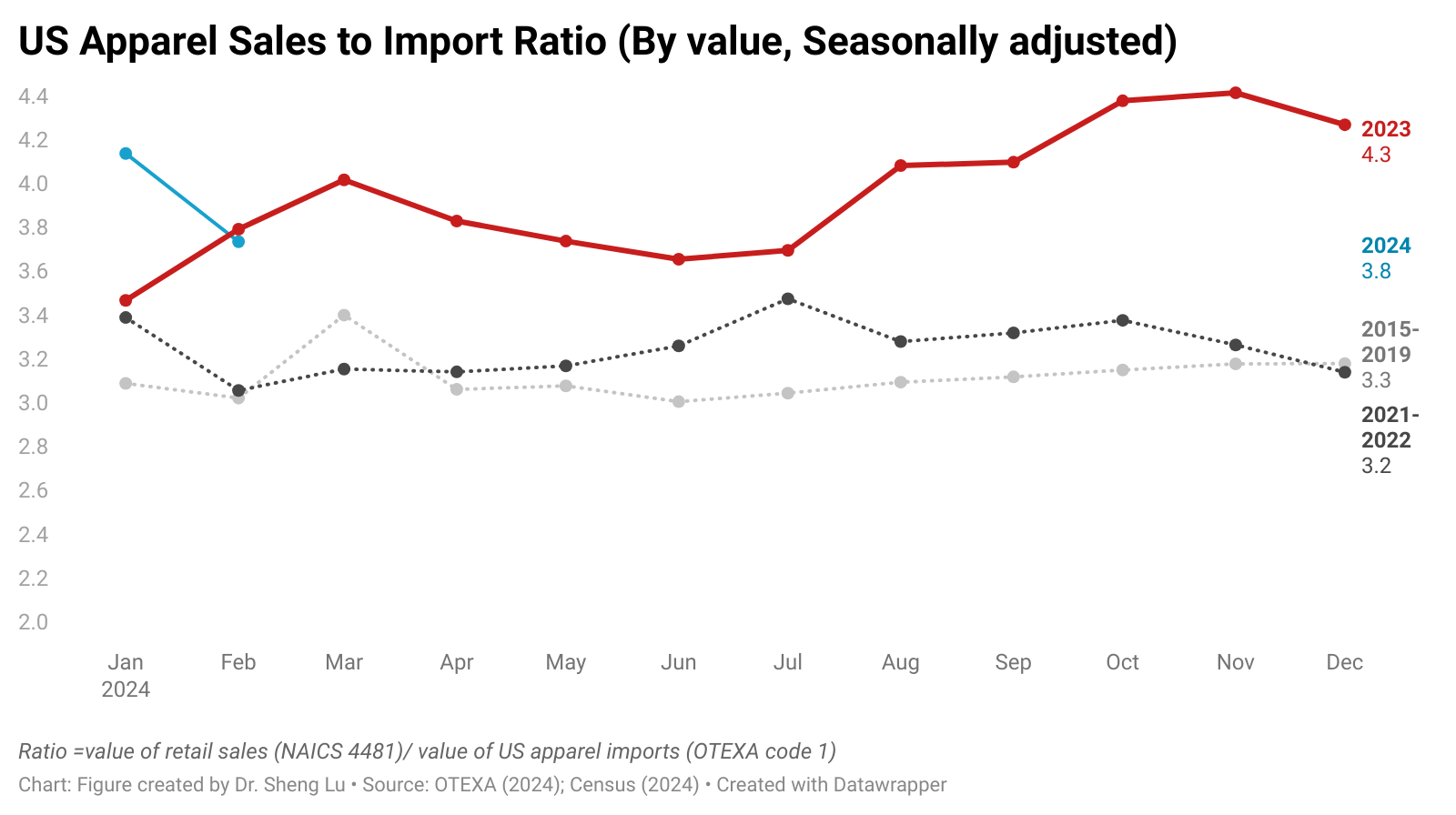

With over 98% of clothing sold in the US retail market being imported today, there exists a strong correlation between US apparel retail sales (NAICS code 4481) and the volume of apparel imports. Between 2015 and 2022, the US clothing sales to clothing import ratio remained consistently around 3.0-3.2 (seasonally adjusted). In other words, the value of retail sales was approximately three times the value of apparel imports. However, in 2023, this ratio increased to 4.0-4.5.

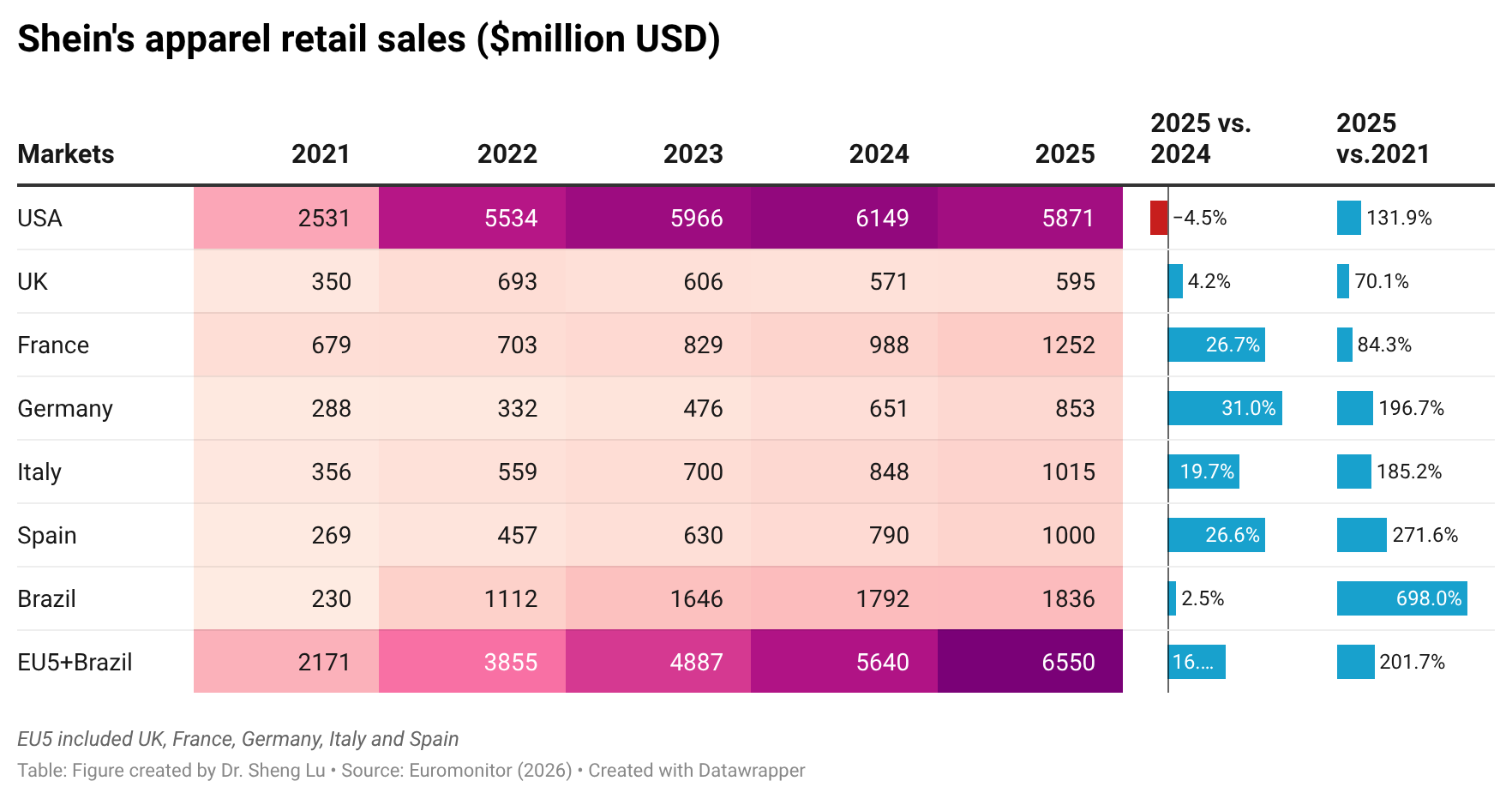

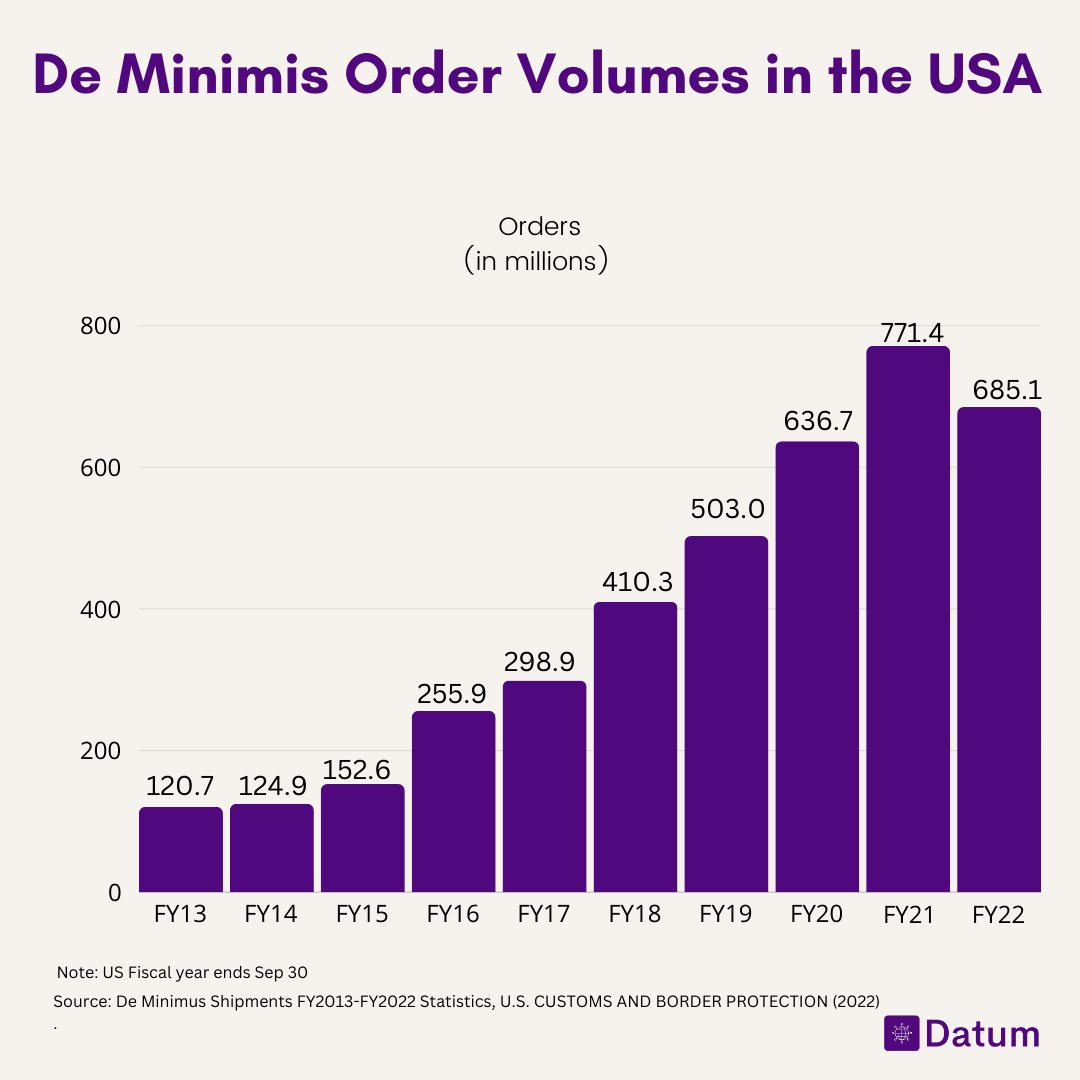

One suspicion is that as more apparel imports came into the US through the de minimis, the official US apparel import data in 2023 was somewhat underreported. Notably, according to Euromonitor, about 40% of US apparel retail sales were achieved through e-commerce in 2023, a substantial increase from 9.4% in 2010. Likewise, with US customs tightening controls on “small package shipments” and enhancing UFLPA enforcement, more imports likely began entering through the standard procedure in recent months, which explains why the US apparel sales to import rato fell back to 3.8 in February 2024.

On the other hand, some say the lowered US apparel import volume in 2023 was due to retailers’ efforts to control inventory levels. Data shows that US clothing stores’ stock-to-sales ratio in the last quarter of 2023 averaged 2.34, slightly lower than 2.43 from 2015 to 2019, but was higher than 2.19 back in 2021. In other words, while there was some effort by retailers to control inventory (as seen by the ratio being lower than pre-pandemic levels), it wasn’t a significant enough change to have a large impact on import demand. Also, considering that apparel is a seasonal product, it doesn’t seem too likely that retailers would risk losing sales opportunities during the most critical selling season of the year (i.e., 4th quarter) by promoting outdated items instead of stocking new ones on the shelf.

Question 3: Why did Asian countries export more apparel to Mexico?

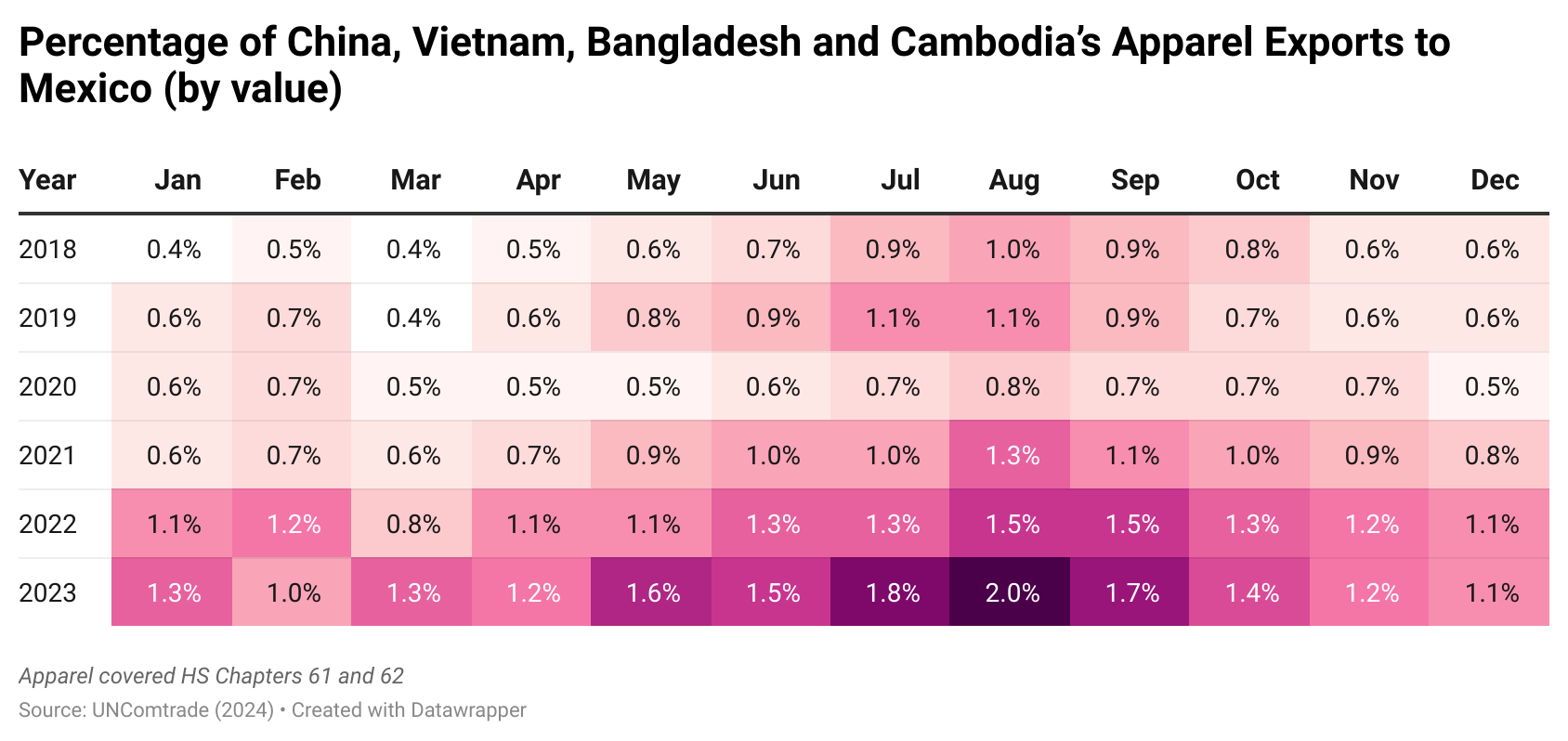

As a developing country, Mexico is not traditionally a leading apparel import market due to consumers’ limited purchasing power and the sufficient local apparel supply. Take China, Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Cambodia, the four top Asian apparel exporting countries (Asia4), for instance. Between 2018 and 2020, Mexico typically accounted for 0.4%-0.7% of Asia4’s total apparel exports. However, since 2022, Asia4 has almost doubled its apparel exports to Mexico (i.e., increased to 1.5%-2.0%). Moreover, during the same period, the percentage of Asia4’s apparel exports to the United States declined from 27% to below 20%, especially in the last quarter of 2023.

What’s behind the increase in Asian countries’ apparel exports to Mexico needs to be investigated further. As noted earlier, Mexico itself is a leading apparel-producing country. Also, according to Euromonitor, the clothing market in Mexico stayed relatively stable at around 7.6%-7.9% of the size of the US from 2017 to 2023 (in quantity). In other words, Mexico’s increased import demand for Asian clothing doesn’t make much sense.

Others suspect some Asian apparel exports to Mexico eventually entered the US market either by taking advantage of the de minimis rule or the US-Mexico-Canda (USMCA) trade agreement. However, the exact size of this particular trade flow calls for further investigation.

By Sheng Lu