(Photo: Courtesy of the AAFA)

(Photo: Courtesy of the AAFA)

Nate Herman is the Vice President of the American Apparel and Footwear Association (AAFA). Mr. Herman manages AAFA’s regulatory and legislative affairs activities, advocating on behalf of, and providing information to, the industry on international trade and corporate social responsibility issues. Mr. Herman also handles product safety, customs, transportation and other technical (slip resistance, safety toe, etc.) issues as well as labeling matters for AAFA’s footwear members as co-leader of AAFA’s Footwear Team. In addition, Mr. Herman develops all apparel and footwear industry data and statistics as AAFA’s resident economist. Prior to joining AAFA, Mr. Herman worked for six years at the U.S. Department of Commerce’s International Trade Administration (ITA) assisting U.S. firms in entering the global market. Mr. Herman spent the last two years as the Department’s industry analyst for the footwear and travel goods industries.

Interview Part

Sheng Lu: First of all, would you please make a brief introduction of AAFA to our students, including your history, your current members, your key missions and main functions?

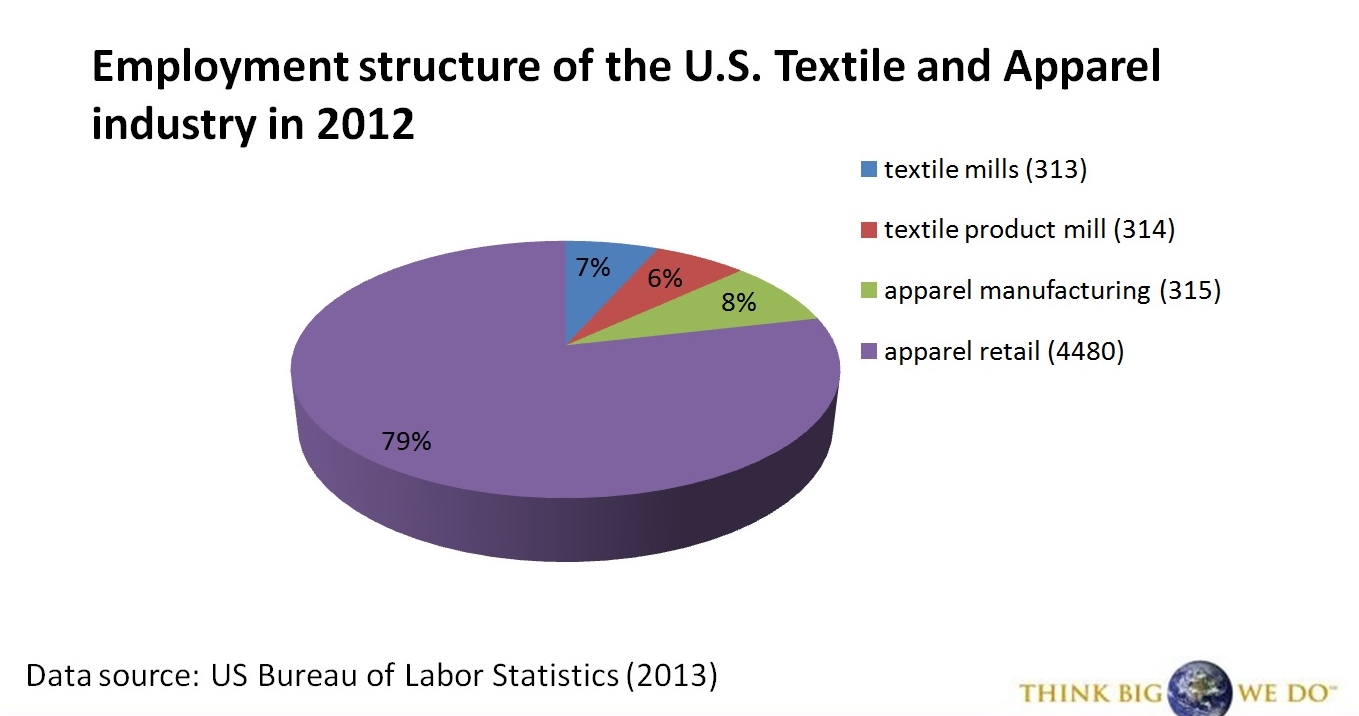

Nate Herman: Representing more than 1,000 world famous name brands, the American Apparel & Footwear Association (AAFA) is the trusted public policy and political voice of the apparel and footwear industry, its management and shareholders, its four million U.S. workers, and its contribution of $350 billion in annual U.S. retail sales. AAFA was formed in 2001 following a merger of the American Apparel Manufacturers Association and Footwear Industries of America.

AAFA stands at the forefront as a leader of positive change for the apparel and footwear industry. With integrity and purpose, AAFA delivers a unified voice on key legislative and regulatory issues. AAFA enables a collaborative forum to promote best practices and innovation. AAFA’s comprehensive work ensures the continued success and growth of the apparel and footwear industry, its suppliers, and its customers.

We achieve these goals through aggressive advocacy on Capitol Hill and before the Administration on the issues most important to the U.S. apparel and footwear industry. AAFA also hosts more than 50 conferences, seminars, workshops, and webinars both in the United States and around the world to ensure the industry is able to comply with growing state, federal, and international regulations.

Sheng Lu: AAFA recently released a video clip “What do we wear”, which is very encouraging and eye-opening to our students. What makes AAFA create this video and what specific information you would like to deliver to the audiences?

Nate Herman: A few years ago, we were asked a question during a meeting with a top-ranking senator. “What is the economic impact of your industry?” We didn’t have an answer, which didn’t help policy makers see the important jobs within our industry and our significant contribution to the U.S. economy. That led to the launch of our “We Wear” brand.

You see, when we get dressed each day, we wear more than clothes and shoes. We wear four million U.S. jobs. We wear intellectual property. We wear social responsibility. Our new video is a visual reminder of our important mission and economic impact. We use it to educate policy makers, administration officials, the industry, and consumers about our industry and how vital we are to the overall health of the U.S. economy.

Sheng Lu: One phrase often used by AAFA is your member companies “produce globally and sell globally”. How should our students understand the global nature of today’s apparel industry?

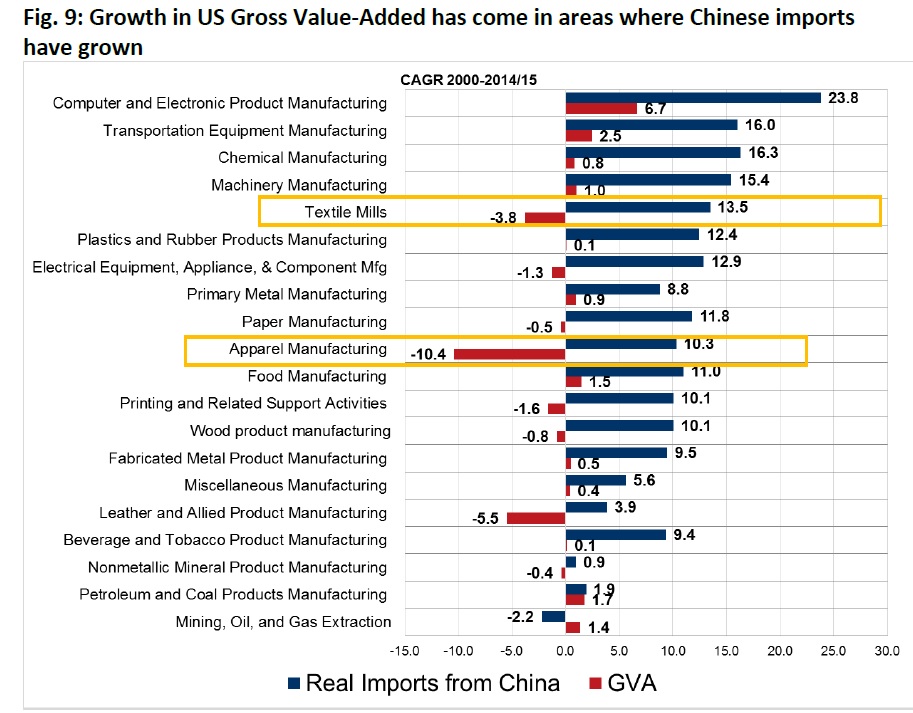

Nate Herman: The apparel and footwear industry is on the frontlines of globalization. In fact, our industry’s supply chain is the most global supply chain in the history of commerce.

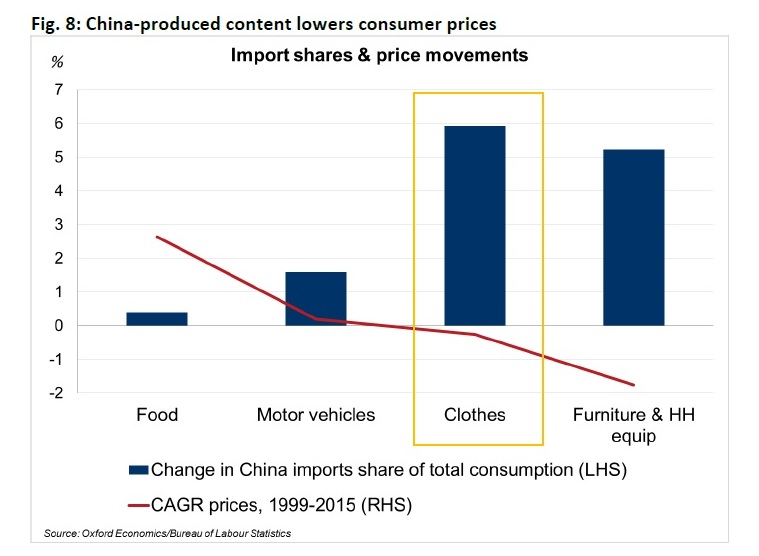

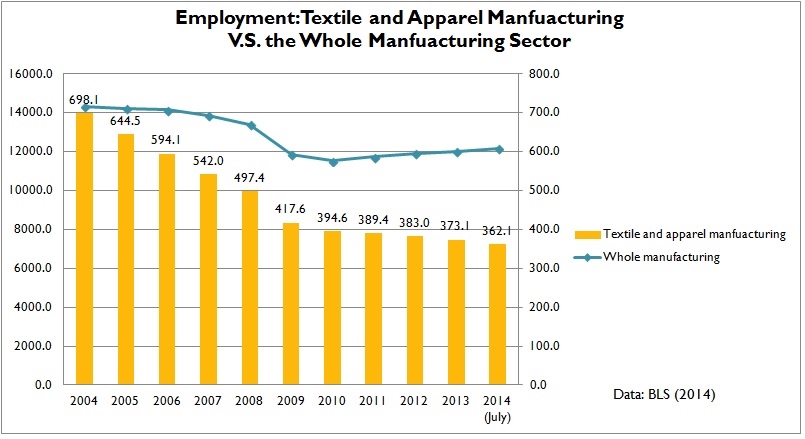

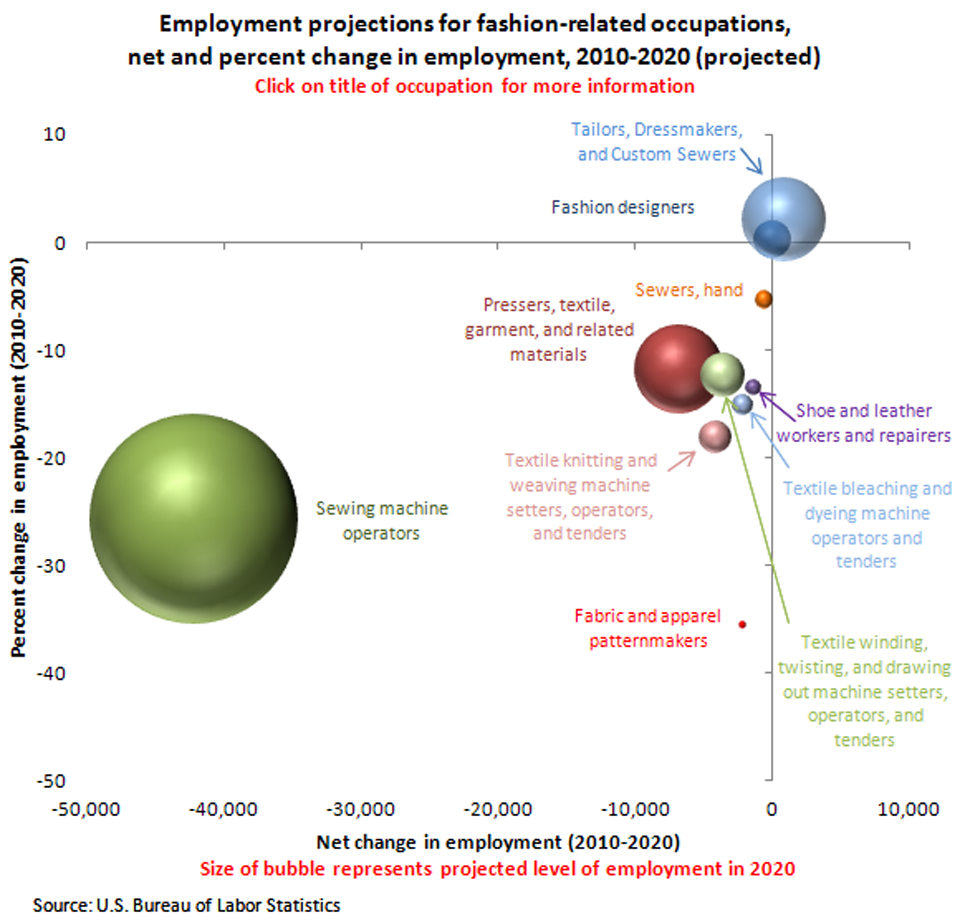

Simply put: We are a nation of 330 million importers. In 2012, 97.5 percent of the apparel and 98 percent of the footwear sold in the United States was produced internationally. This model allows families to spend less of their family budgets on clothing and shoes while still getting more bang for their buck.

Sourcing is made possible through strong and positive trade relationships with a variety of countries, including China, Mexico, Vietnam, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Colombia, Honduras, the Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and more. Companies even source product from the United States. Sourcing decisions are often made through serious processes that evaluate a country’s trade programs, environmental record, social responsibility standards, intellectual property protections, material and labor costs, shipping time, and reliability of sourcing partners.

At the same time, don’t ignore the rest of the world. The United States only represents just five percent of the world’s population. So when a company sources from China or Vietnam, they are sending products all over the world through a complex supply chain. One of our goals at AAFA is to help ensure the entire world has access to world famous U.S. name brands.

Sheng Lu: The Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) are two buzzwords nowadays. From the perspective of AAFA, why should the US apparel industry care about these two agreements?

Nate Herman: Trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and the Trans-Atlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) offer U.S. name brands direct market access to new sourcing and retail markets. For example, the United States and the European Union, under TTIP, accounts for more than 40 percent of global clothes and shoes retail sales.

Trade agreements also provide opportunities to harmonize regulations to make it easier to do business in the global market. For instance, the United States maintains strict product safety standards. Through trade agreements, we can make regulations consistent to ensure if a shirt is safe in one country it’s safe in another. This prevents redundant testing costs, which ultimately makes clothes and shoes cheaper for consumers.

Sheng Lu: Last year, several tragedies happened in the Bangladesh garment factories raised the public awareness of the corporate social responsibility issues in the apparel sector. How has the tragedy changed the business practices in the apparel sector from your observation?

Nate Herman: Over the past year, the U.S. apparel and footwear industry has rallied together to address significant social responsibility challenges, including worker safety. In fact, we’ve never seen the industry come together so fully in a spirit of collaboration. Safety inspections, training, and fire safety prevention have been or are now part of many companies’ compliance programs. AAFA supported the creation of the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, an industry-led effort to prevent future tragedies in Bangladesh. While all these positive steps encourage us, we know our social responsibility and environmental work will never be finished. We can always do better.

Sheng Lu: Look ahead in 2014, what top issues in the apparel industry you would suggest our students to watch?

Nate Herman: 2014 is already shaping up to be a busy year for the U.S. apparel and footwear industry. One major trend we are watching is the continued growth of e-commerce and Omni-channel retail. You see, the point of sale is just the starting point of a long – and global – supply chain. We will see sourcing patterns and business models change as retail shifts away from brick-and-mortar shopping to online e-commerce. We are now beginning to focus on new ideas like online privacy and data security, terms the industry didn’t have to focus on 10 years ago.