The Sixth Anniversary of Post-quota Era:

New Patterns of World Textile and Clothing Trade and Critical Trade Policy Issues

By Sheng Lu

Keywords: Post-quota era, world textile and clothing trade, trade policy

Impact of the elimination of the 40-year textile and clothing (T&C) quota system on January 1, 2005 has always been a research interest to scholars in the field. Shifting from a highly-distorted trading environment to a much more market-based competition, reshuffle of the world T&C trade in the post-quota era is widely believed to be unavoidable and will have ripple effects on the future landscape of the global T&C industry (Dickerson, 1999; Nordas, 2004).

After six years of transition, medium and long-term effects of quota elimination have begun to display, attributed to adjustment of business practices of T&A firms in response to the new “rules of the game” (UNIDO, 2009). By taking advantage of such great timing, this study scrutinizes patterns of world T&C trade that have been newly emerged so far in the post-quota era. Capturing these new trends of development at the macro-industry level can both deepen understanding about the 40-year quota system itself and raise awareness of emerging research agendas for world T&C trade.

Three specific post-quota patterns of world T&C trade are discussed in the study:

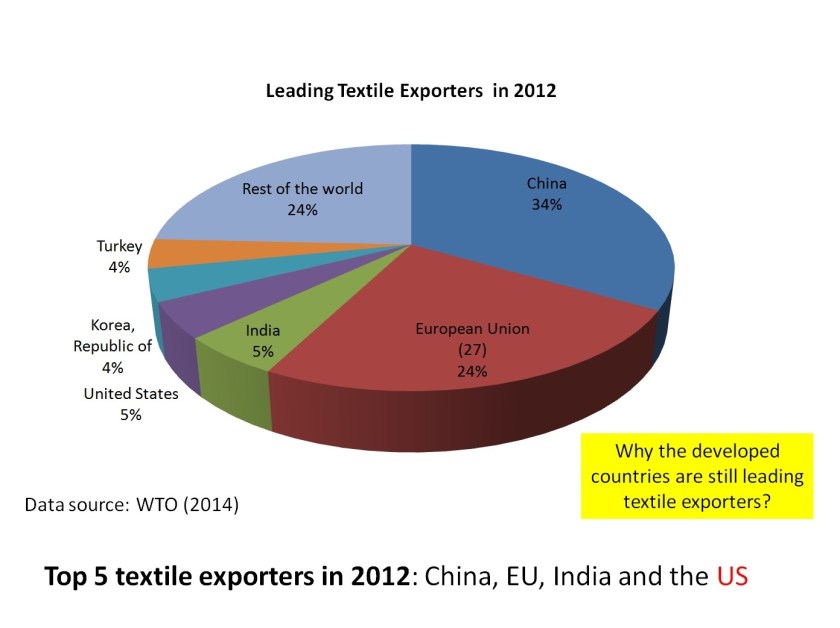

First, non-dominant position of China in world T&C export. At first glance, China increased its market share in world T&C export by roughly 10 percentage points from 2005 to 2008, suggesting China was one of the biggest winners of quota elimination (WTO, 2010). However, a closer look will find: (1) China gained its market share at a decelerating rate over that period, implying China’s export surge at the very beginning of quota elimination was mainly due to the temporary transition effect; (2) At the disaggregated 6-digit HS code level, China’s export performance varied greatly from product to product, implying other exporters was still able to compete with China in the post-quota era by focusing on certain T&C product categories; (3) A number of Asian and European countries other than China also enjoyed robust growth in T&C export since 2005, suggesting China was one of the beneficiaries rather than the only winner of the post-quota era. Last but not least, the emergence of the “China+1” sourcing strategy indicated that T&C importers already started selecting other possible substitution sourcing destination as China’s back-up. In particular, importers were cautions about China’s rising manufacturing cost and the business risks associated with placing “too many eggs in one basket”.

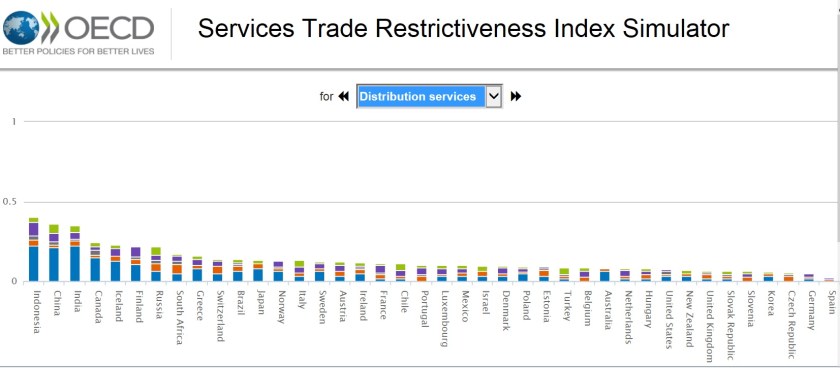

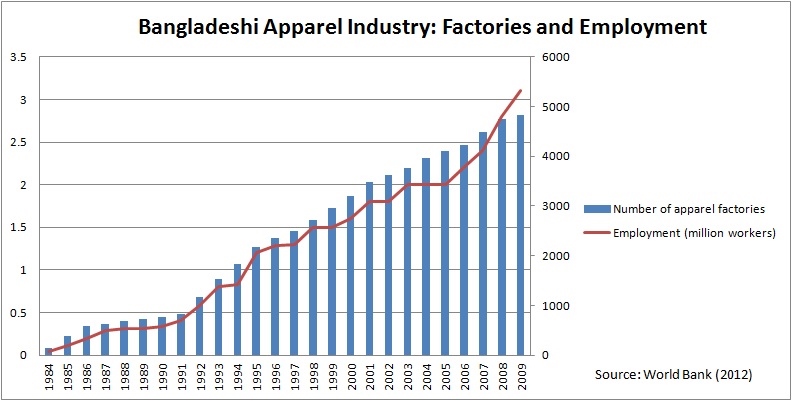

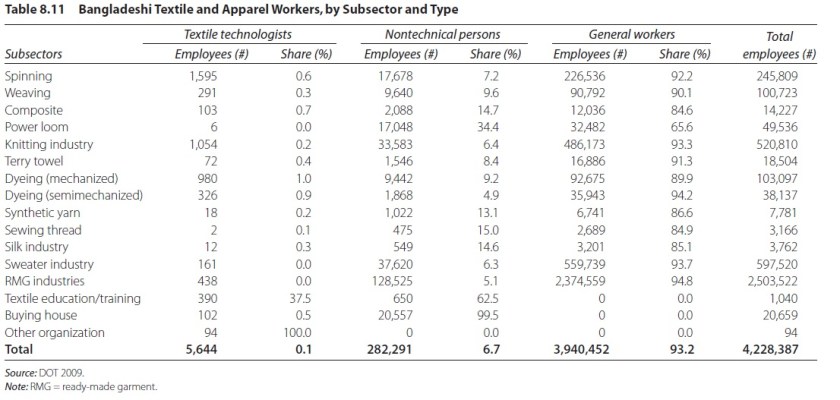

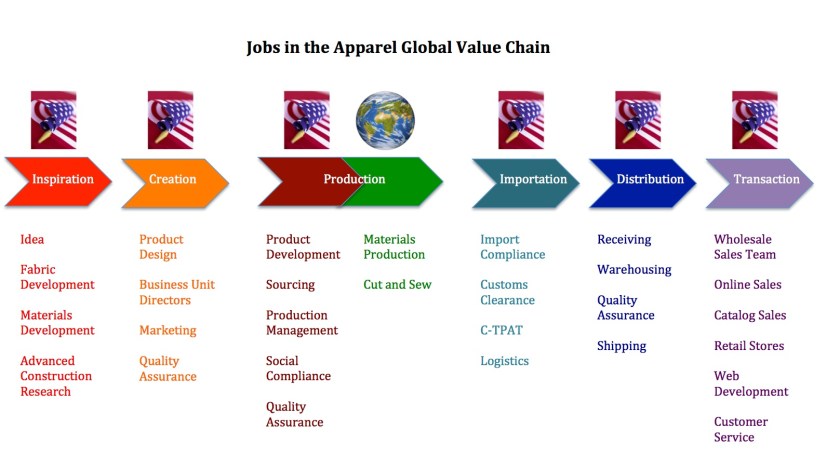

Second, geographic concentration of T&C trade and increasing dependence on textile manufacturing capacity for clothing export. This new pattern is closely associated with changes of buyers’ sourcing practices. Specifically: (1) Market concentration rate (Herfindahl index) in major T&C importing countries, such as the United States, Europe and Japan, quickly went up since 2005 because of buyers’ consolidation of their sourcing channels. Traditional trade patterns such as “triangle manufacturing” and “outward processing trade” which were artificially created by the quota system can no longer justify their rationality of existence when quota restriction were removed. (2) The traditional “Cut, Make and Trim” (CMT) sourcing practice was gradually replaced by full-package sourcing. This shift was largely caused by the upgrading of global T&C value chain, including the transition of branded manufacturers into marketers and retailers’ more active involvement in direct sourcing; (3) Compared to CMT, qualified destination for full package sourcing needs to have the capacity of locally manufacturing textiles. This requirement poses big challenges to many developing countries which haven’t established a sound textile industry yet due to their overall lagged behind economic development. Impacts of full package sourcing on many aspects of the global T&C industry can be further studied.

Third, widening gap of intra-region trade patterns between America and Europe. As one format of vertical division of labor formed by countries in the same region but at different development stages, intra-region trade was a special feature of the world T&C trade, especially in America and Europe (Dickerson, 1999). However, statistics showed that intra-region trade in America quickly dropped from 69% to 55.7% for textiles and 48.5% to 26.9% for clothing from 2004 to 2008 (WTO, 2010). The decline occurred despite the new passage of several free-trade agreements which deliberately include clauses encouraging the using of U.S.-made textile products by neighboring developing countries. Accompanied with lowering share of intra-region T&C trade, imports from Asia keep constant rising in America over the same period. In contrast, share of intra-region trade in Europe remained stable, stood at around 75% for textiles and 82% for clothing. More studies can be done to explore the causes of such widening gap between America and Europe in terms of intra-region trade patterns.

This study also calls for awareness of “unexpected” negative effects of some trade policies on developing countries’ T&C export in the post-quota era. These trade policies include although not limited to: (1) WTO Doha Development Agenda (DDA). The DDA negotiation set the goal to cut import tariff for T&C product worldwide. However, reduced tariff rate will also wear down the real benefits of preferential duty-free treatment enjoyed by some least developed countries when competing with T&C export giants such as China and India; (2) Rule of origin (ROO) provisions in free-trade agreements. ROO originally was developed to ensure preferential treatments be enjoyed only by eligible FTA members. However, as ROO is specific to each FTA, the complexity and inconsistency made many preferential treatments seldom be taken advantage of. ROO further reduces the incentives for developing countries to develop their own textile industry. This put developing countries at a special disadvantage position when buyers are shifting to full package sourcing as discussed above. (3) Generalized System of Preferences (GSP). Aimed at promoting economic growth in the developing world, developed countries allow preferential duty-free entry of imports from eligible developing countries through the GSP program. Ironically, although T&C account for 50%-90% of total exports for many developing countries (WTO, 2010), most T&C importers including the United States and the European Union still reject including T&C in their GSP programs due to opposition from political forceful domestic industries with concerns about import competition. It is a challenge for policy makers in the post-quota era to design a set of fair and rational trading rules under which developing countries can enjoy the benefits of quota elimination and have more opportunities participating in world T&C trade. Academia has its key role to play in this endeavor.

References

Dickerson, K. G. (1999). Textiles and apparel in the global economy. N.J.: Merrill

Nordas, H. K. (2004). The global textile and clothing industry post the agreement on textiles and clothing. WTO discussion papers, 5. Geneva: WTO Publications

United Nations Industrial Development Organization, UNIDO (2009). The Impact of Institutions on Structural Change in Manufacturing: the Case of International Trade Regime in Textiles and Clothing. Vienna: Austria

World Trade Organization, WTO. (2010). World Trade Statistics, Geneva: Switzerland