The full article is published in Just-Style and below is the summary:

India’s Textiles and Apparel Production

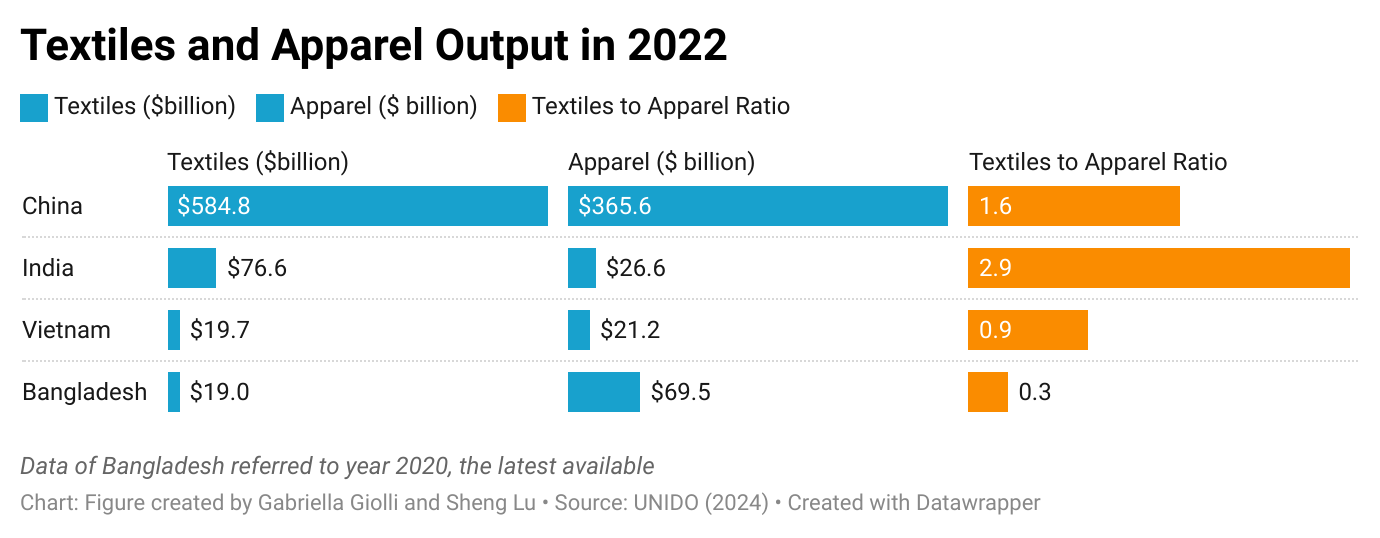

Data from the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) shows that India produced around $76.5 billion in textiles and $26.64 billion in wearing apparel in 2022. Although still smaller than China’s, this production scale has already surpassed that of most other Asian countries, including Vietnam. Behind these numbers were India’s over 4,000 ginning factories, 3,500 textile mills, and around 45 million workers directly employed by the textile and apparel sector.

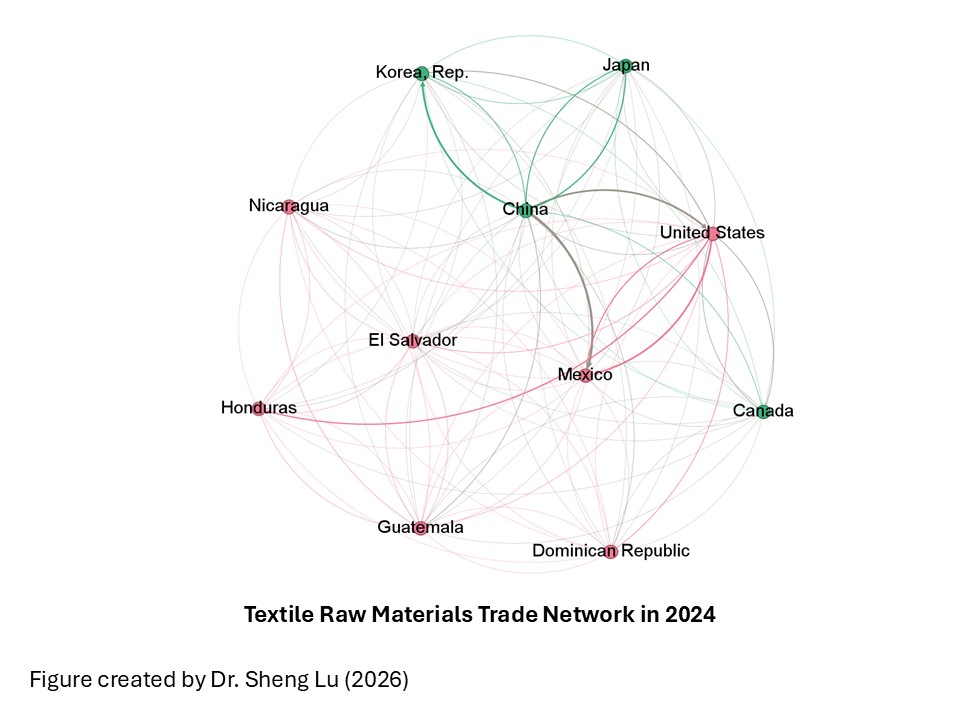

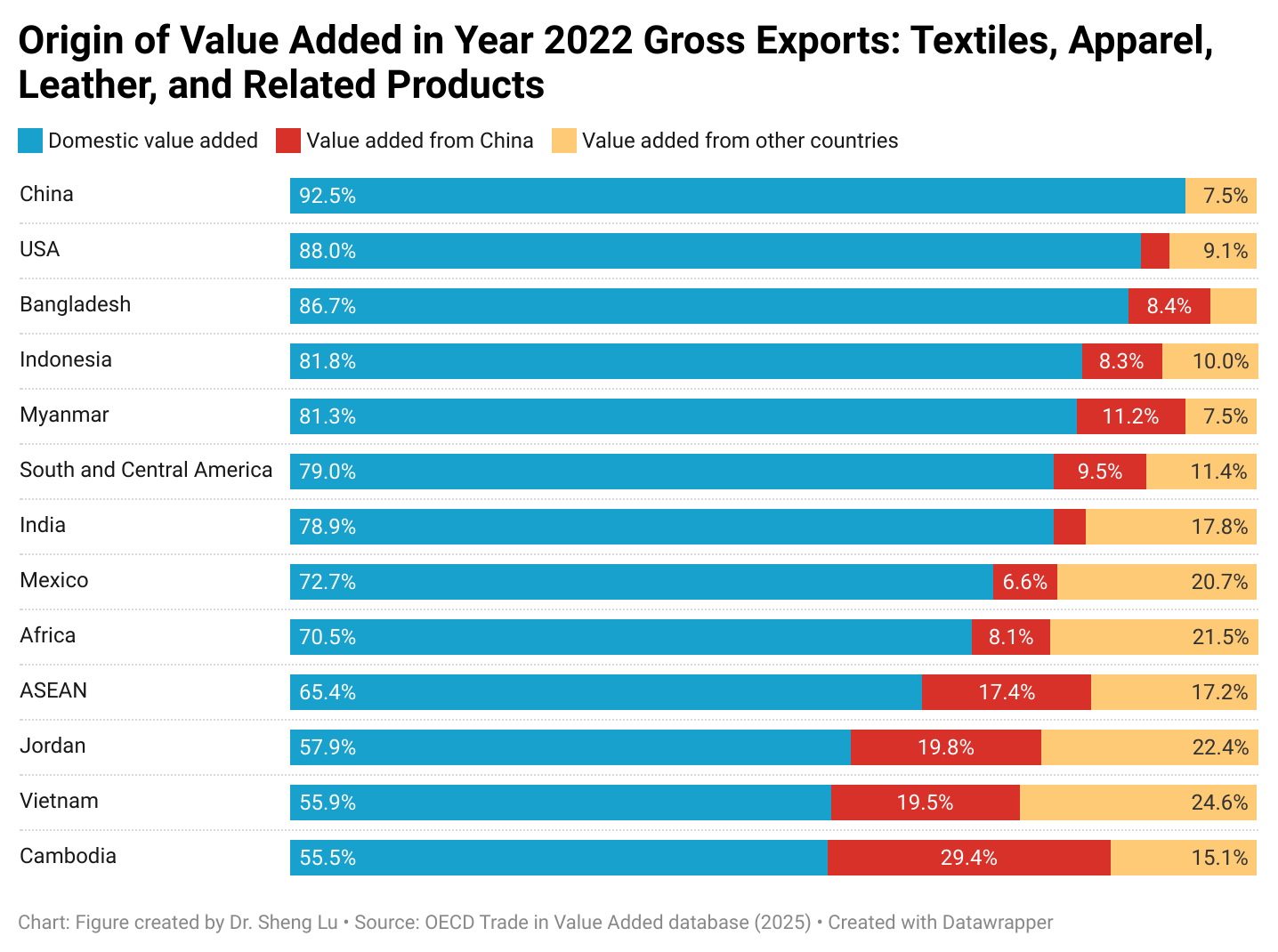

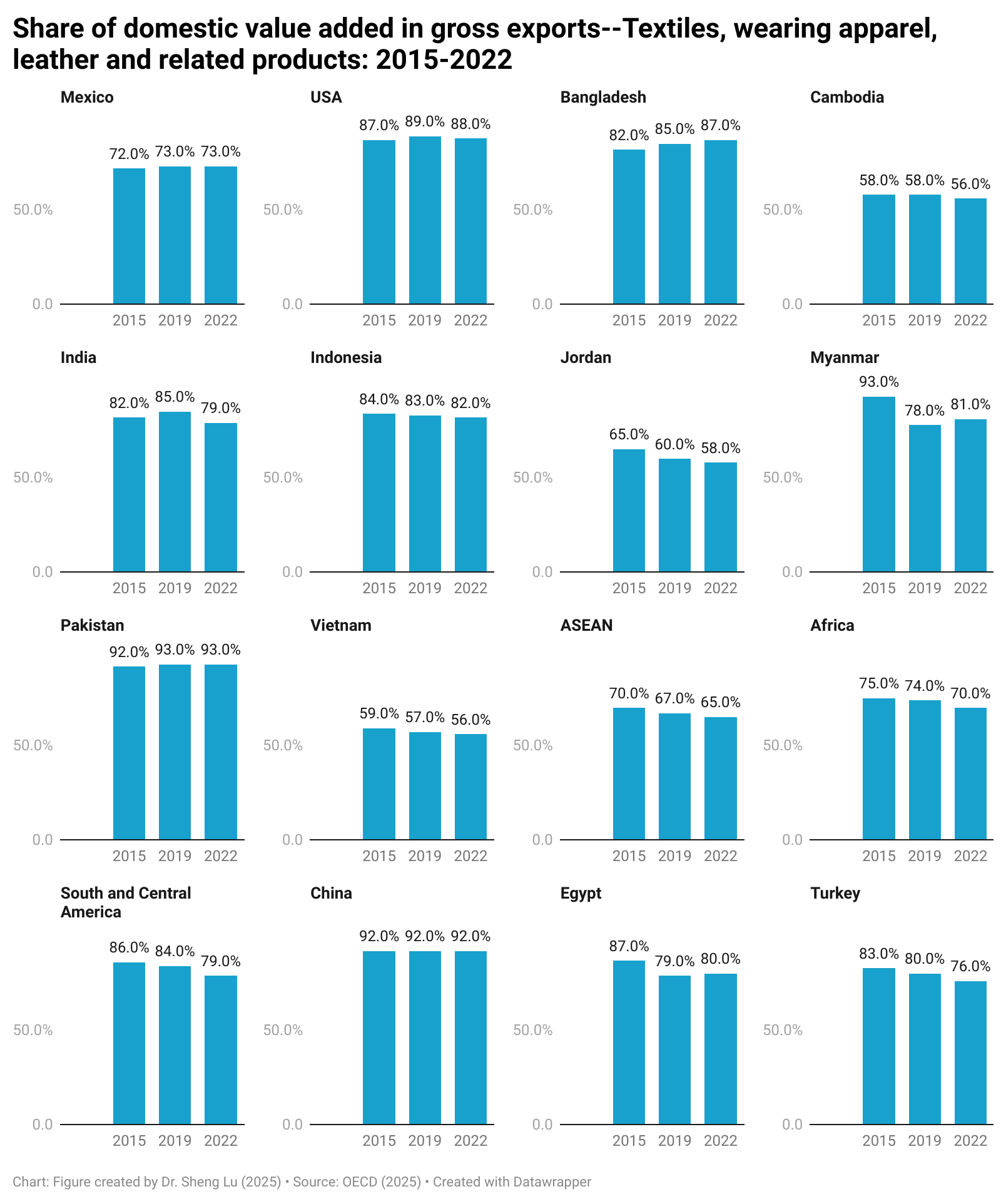

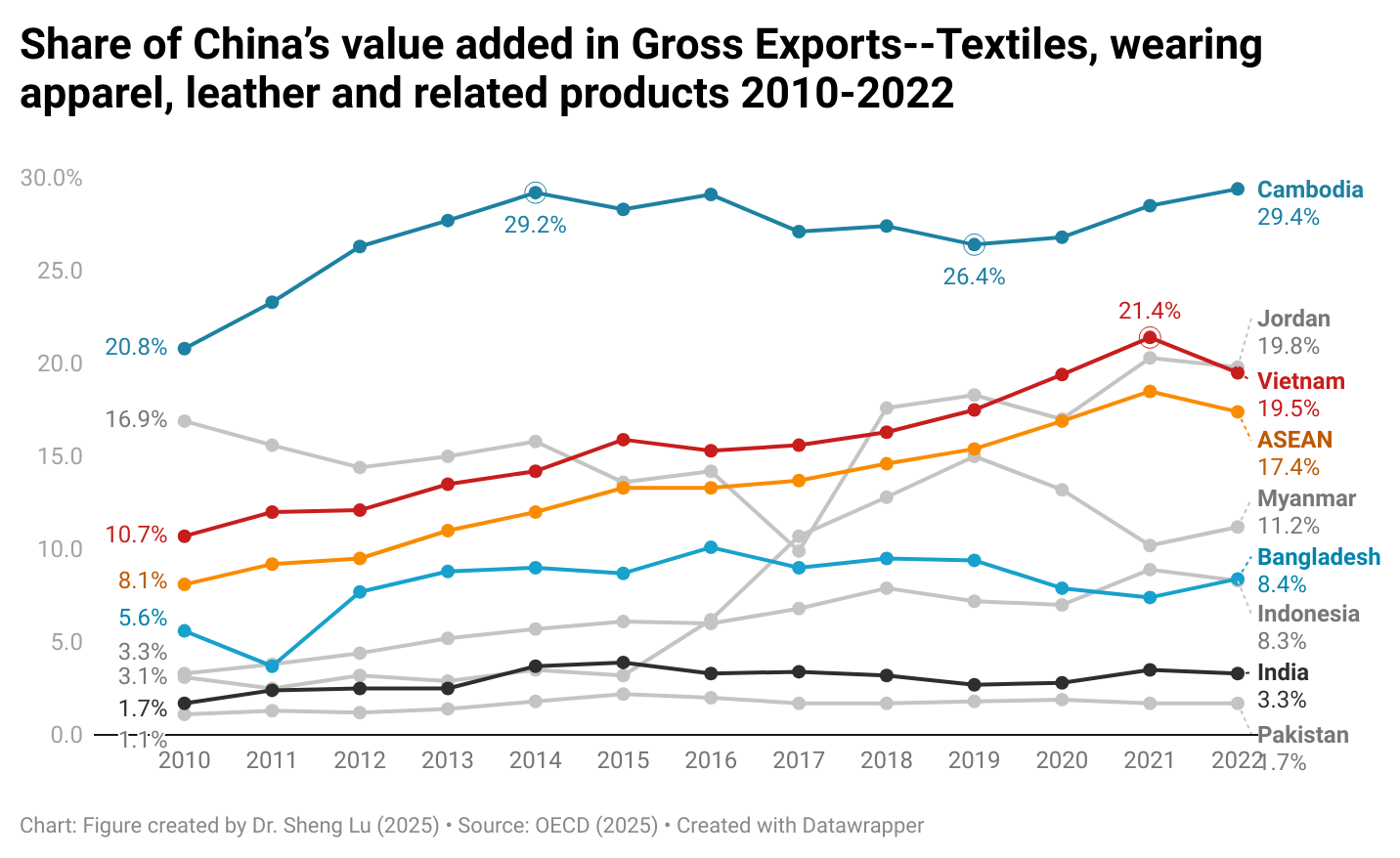

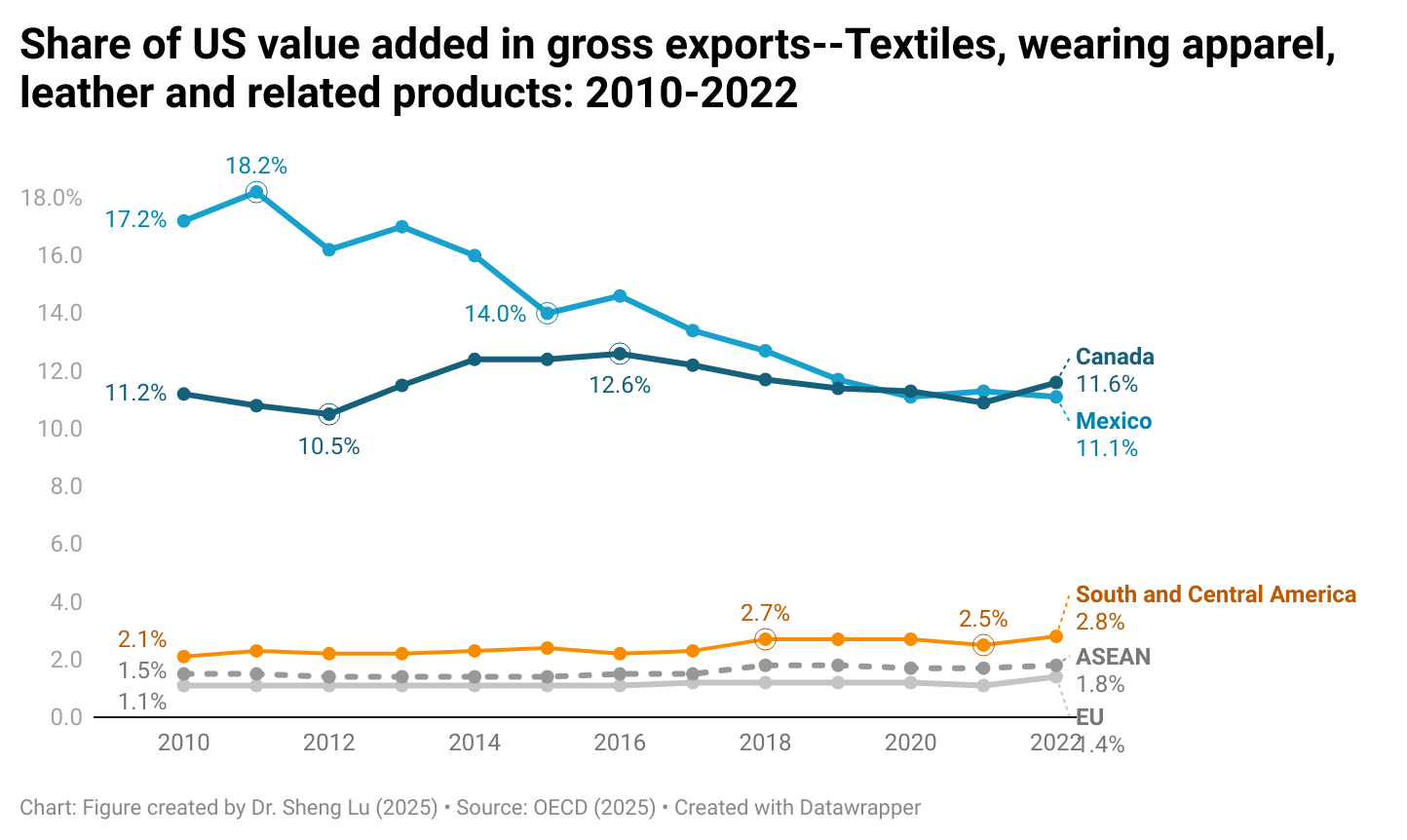

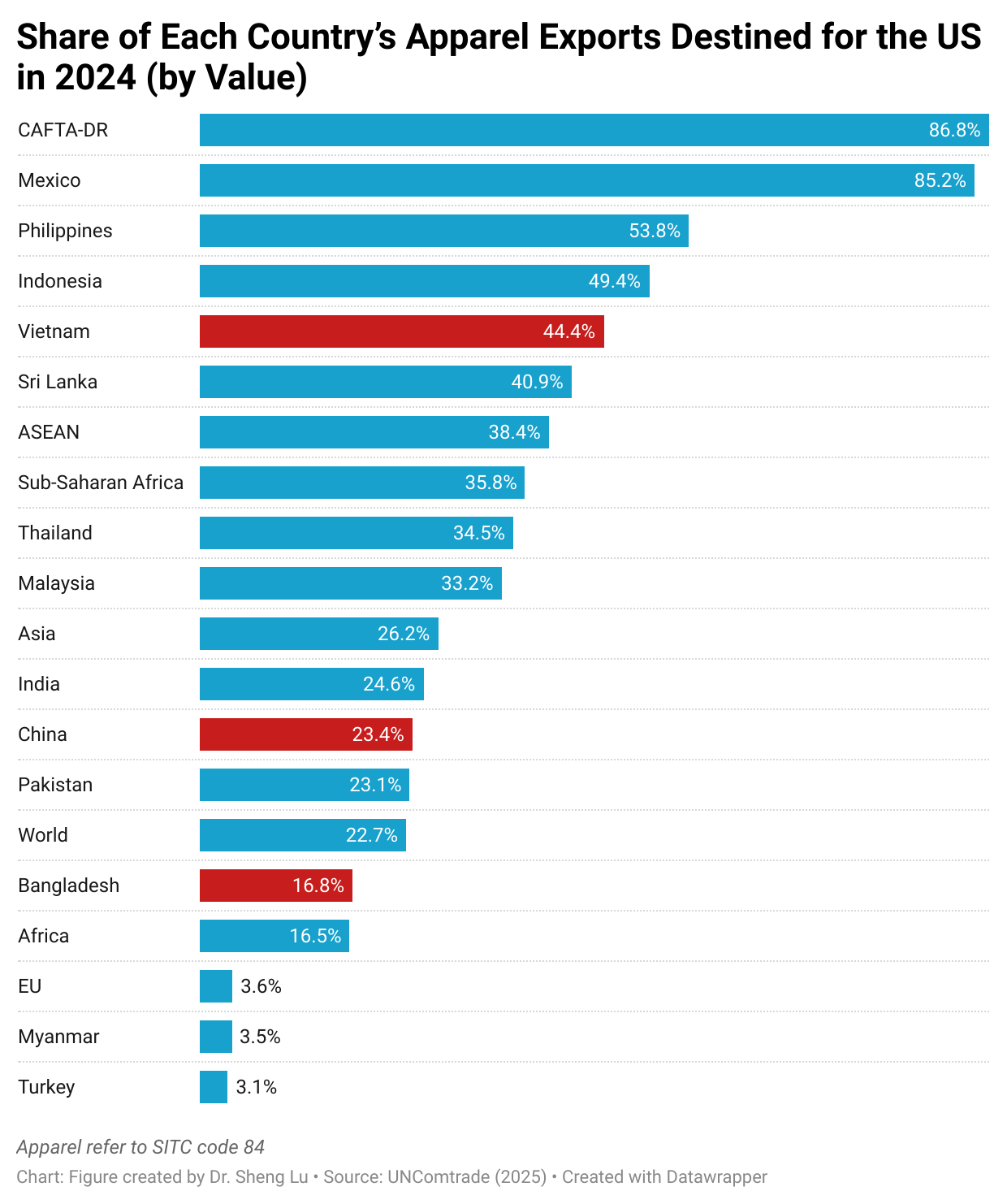

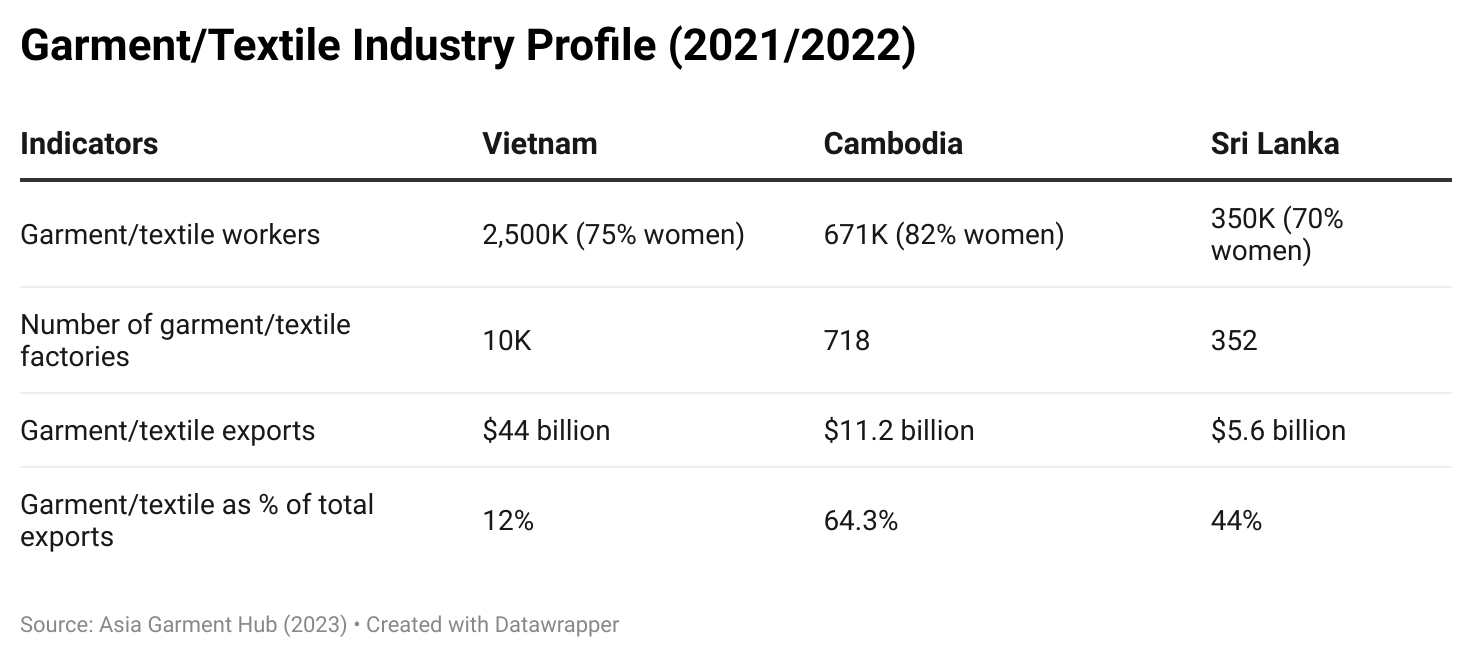

India is one of the world’s largest textile fiber producers, including regular cotton, organic cotton, silk, polyester, and viscose. India also has more advanced local textile manufacturing capabilities than most other developing apparel-exporting Asian countries, allowing it to benefit from a vertically integrated local textile and apparel supply chain. A recent U.S. International Trade Commission (USITC) study noted that more than 90 percent of India’s textile raw materials needed for its apparel production can be sourced domestically. In comparison, as the World Trade Organization (WTO) global value chain analysis estimated, more than 64 percent of Vietnam’s apparel exports in 2022 contained foreign-made content (i.e., imported yarns and fabrics), 57 percent for Cambodia, 49 percent for Indonesia, and 33 percent for Bangladesh.

India’s Apparel Export

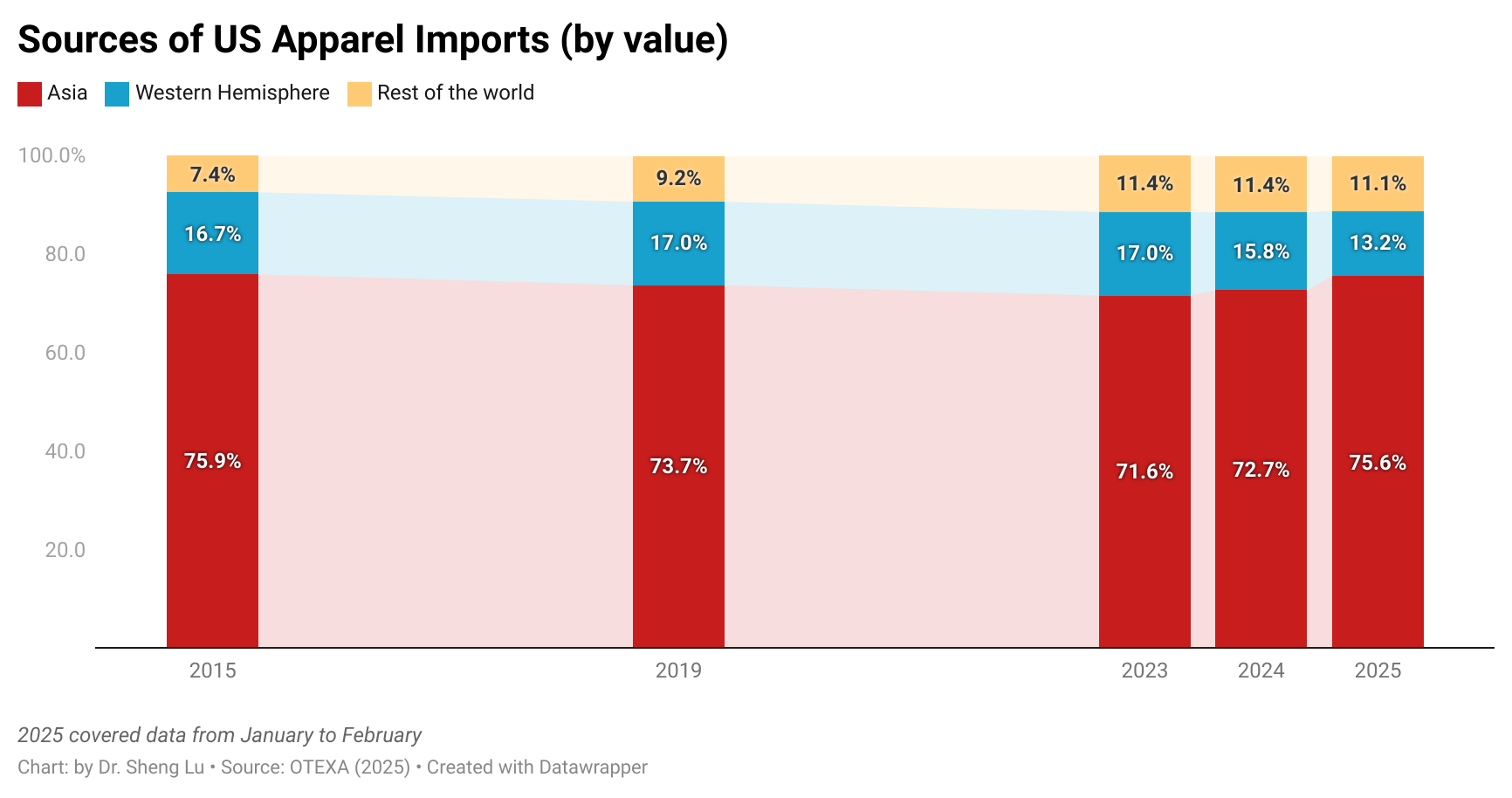

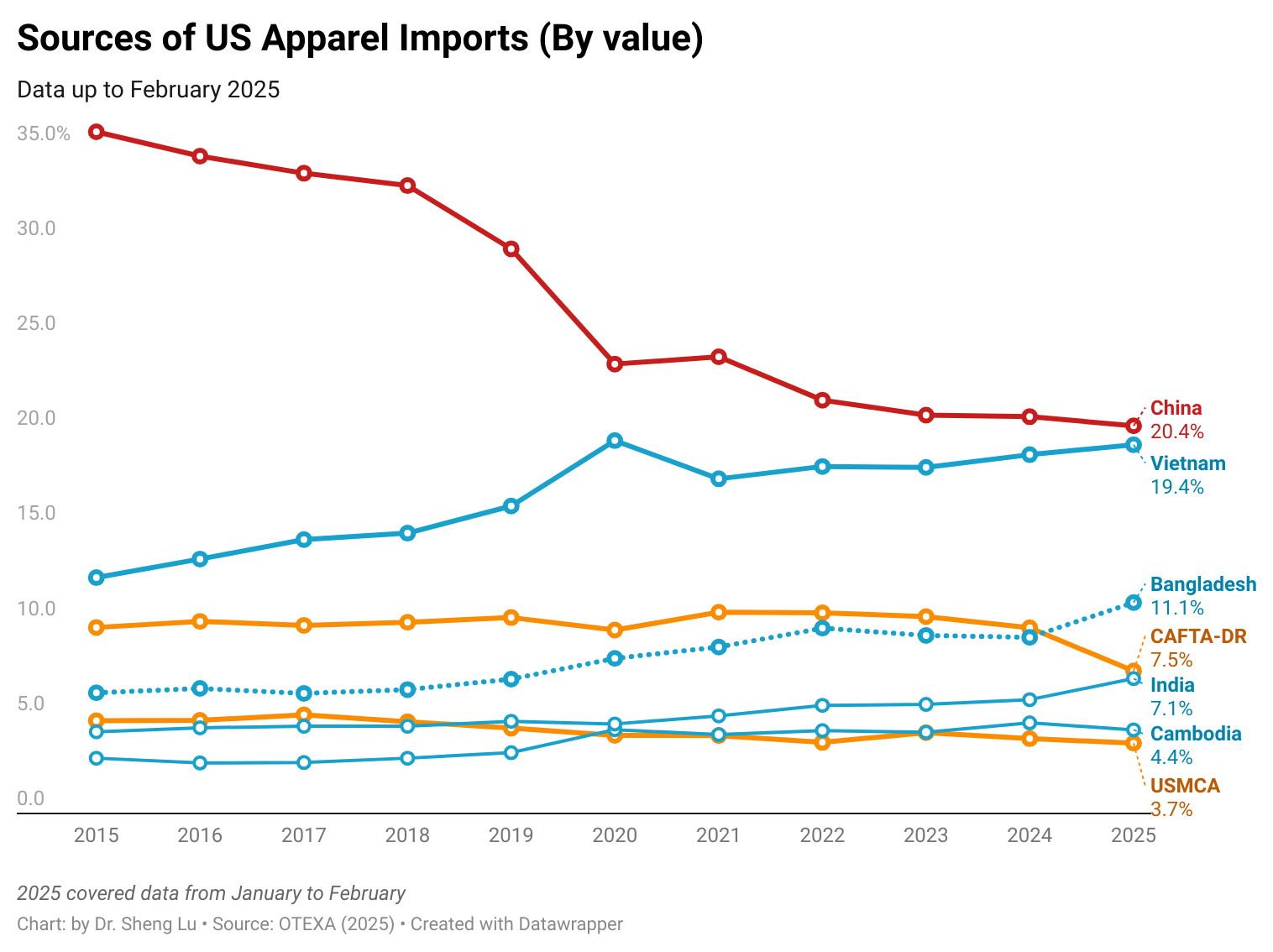

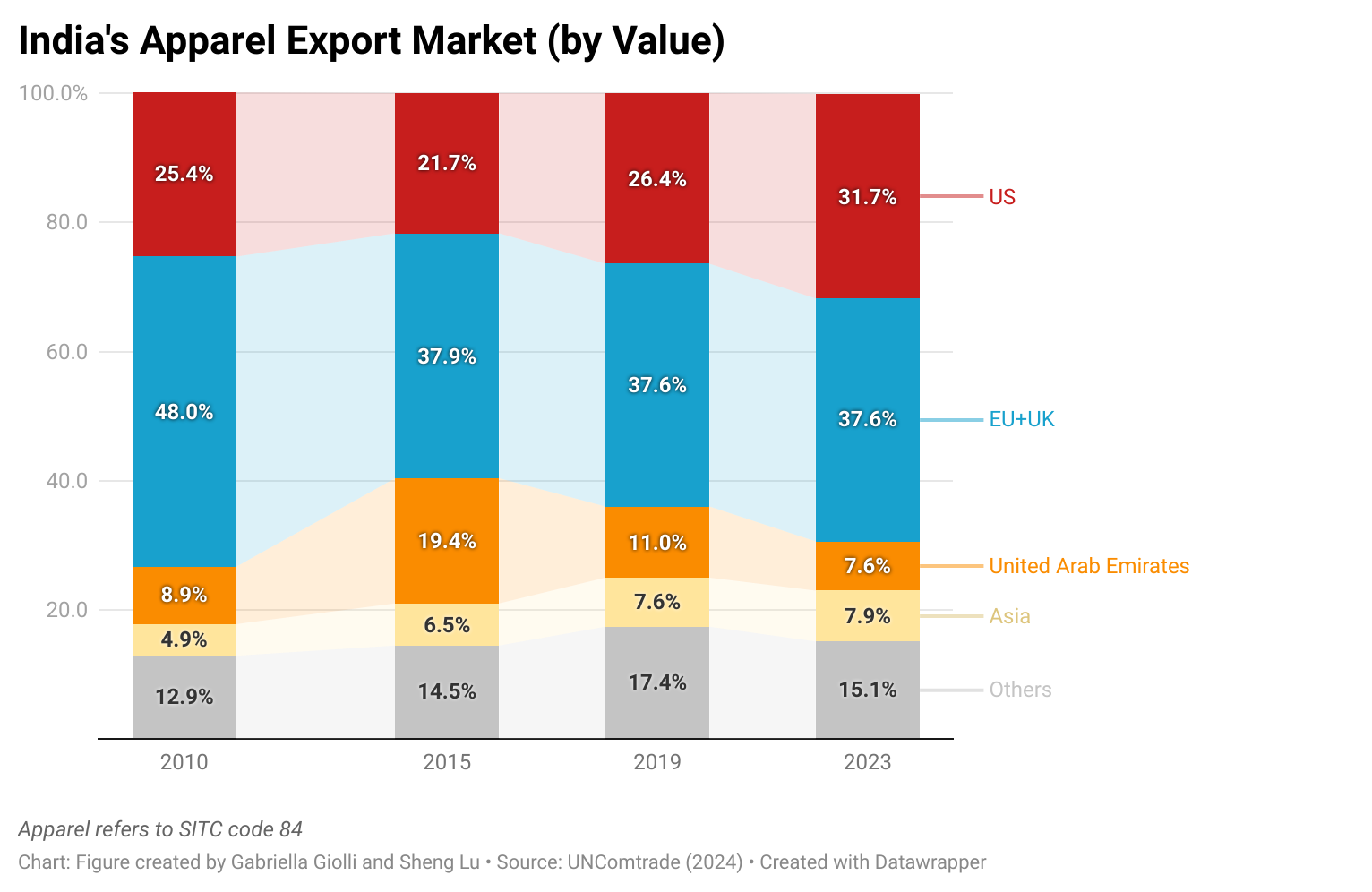

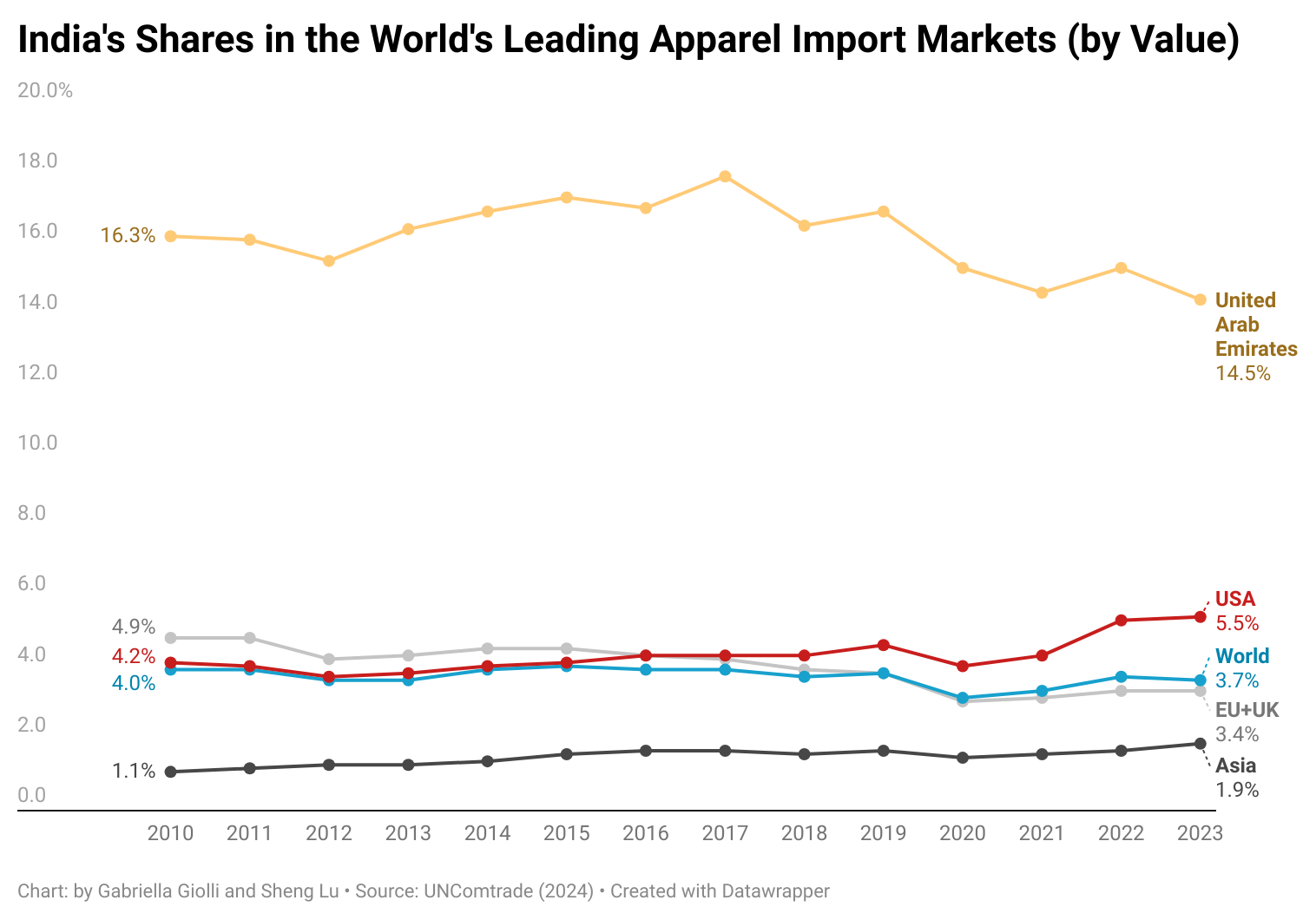

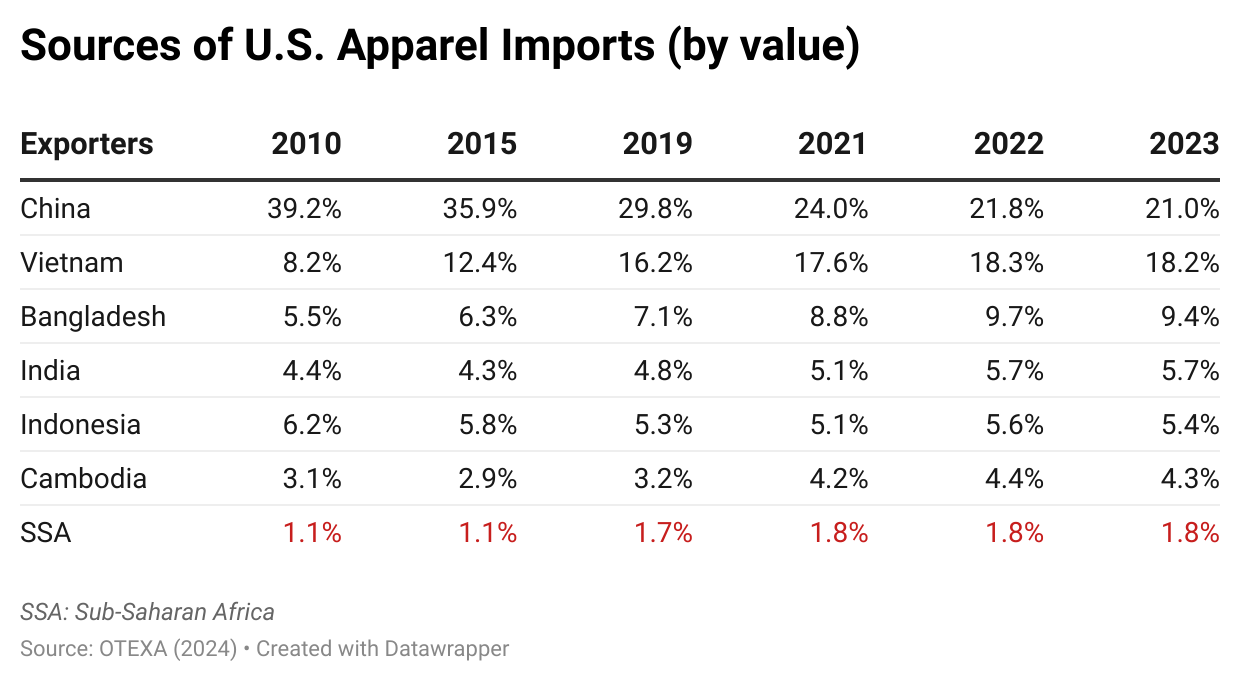

India remained a much smaller apparel exporter than China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh. According to the World Trade Organization (WTO), India exported about $15 billion in apparel in 2023, ranked the world’s sixth largestor 2.8 percent of the global total. Similarly, in 2023, India accounted for 5.5 percent of U.S. apparel imports and 3.5 percent of the EU, showing its position as a significant supplier but not among the largest. However, unlike most other developing Asian countries, India exports less than half of its apparel output due to its massive domestic market with a population of 1.43 billion. This implies that India’s substantial untapped apparel export potential should not be ignored.

Why Sourcing from India?

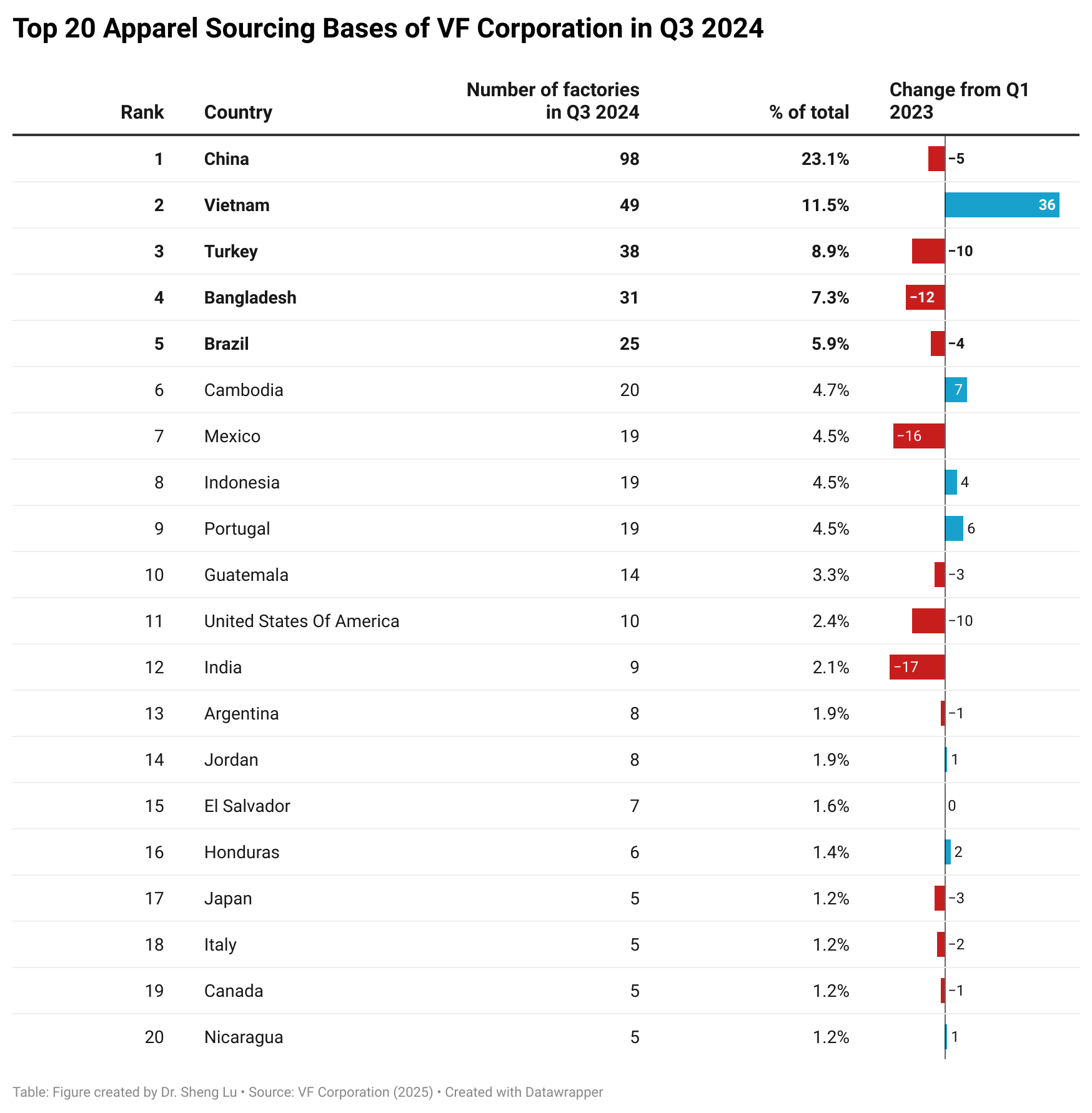

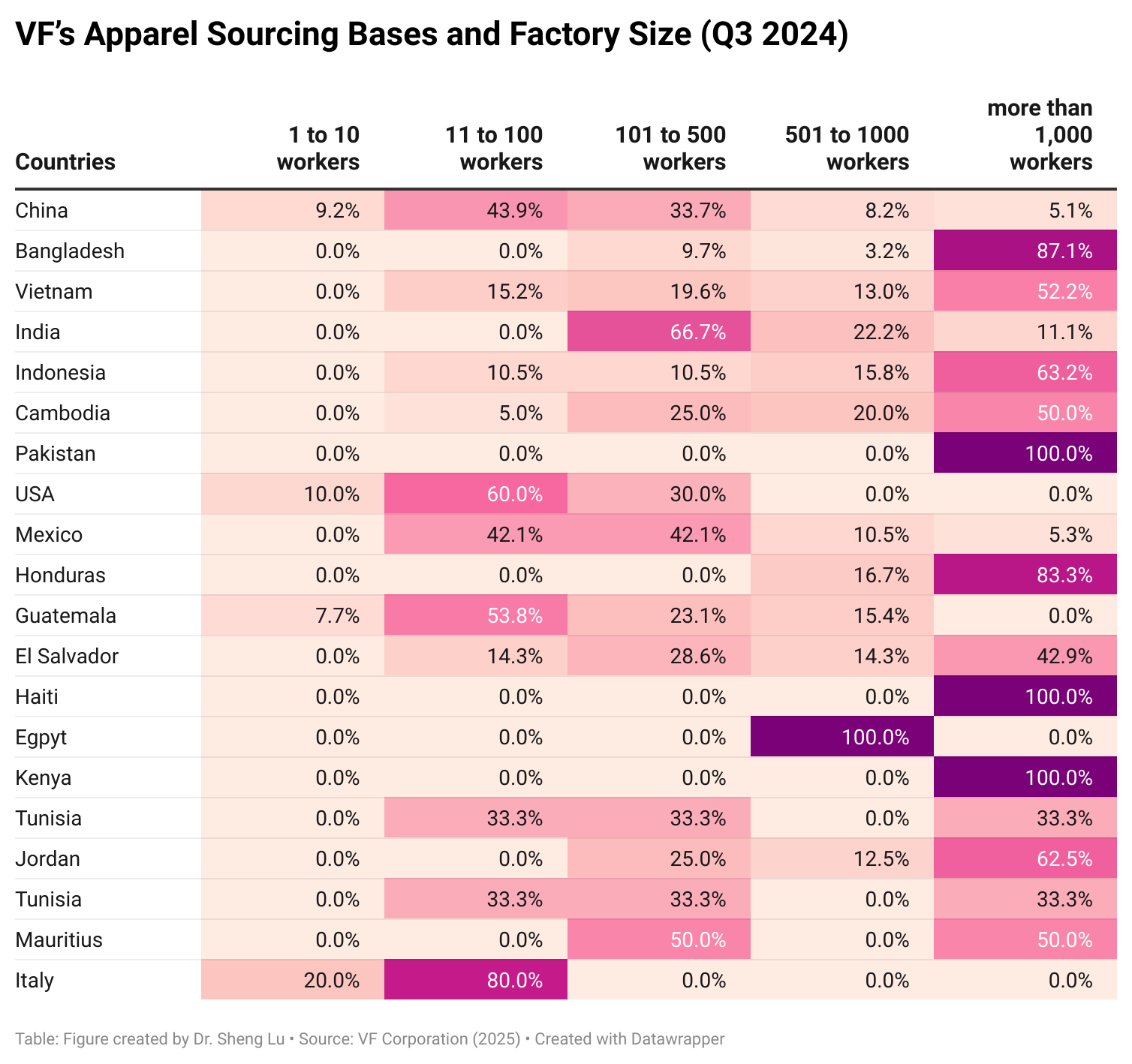

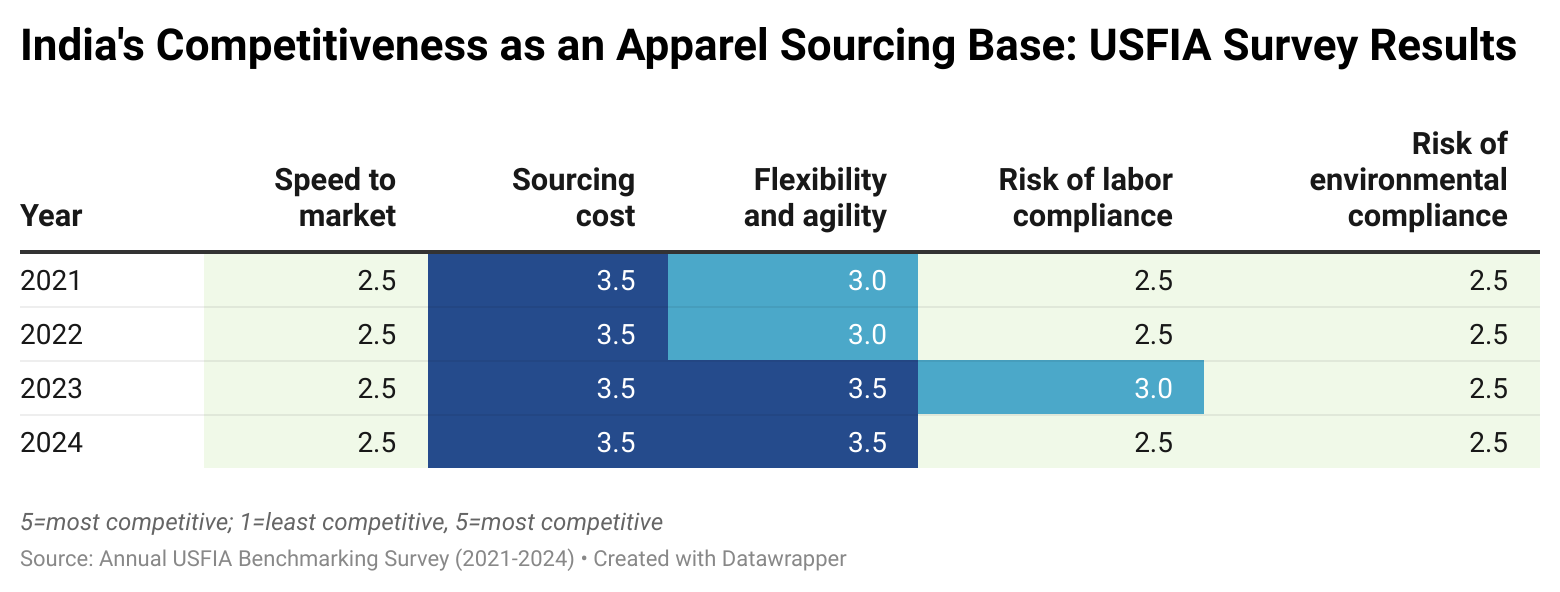

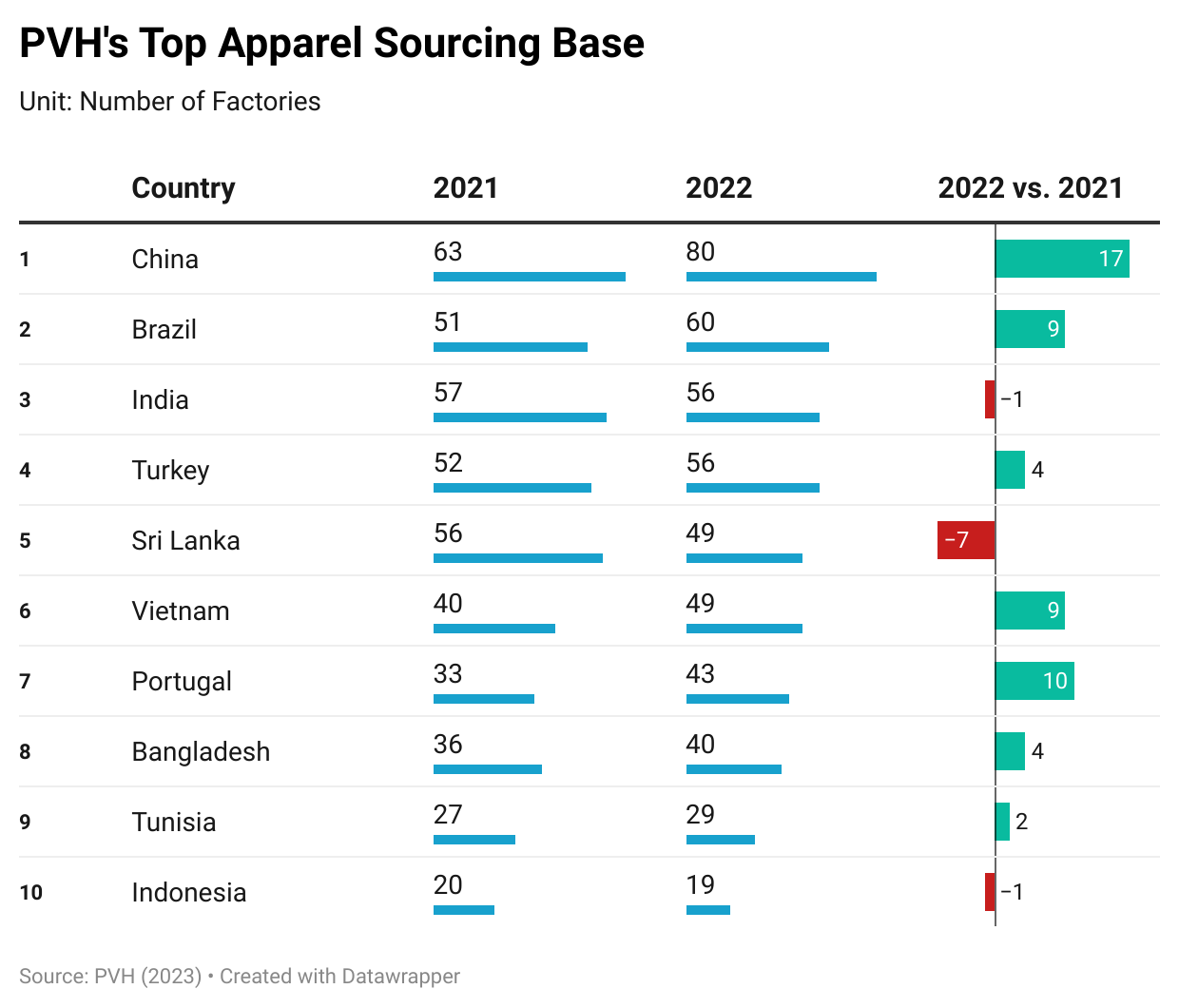

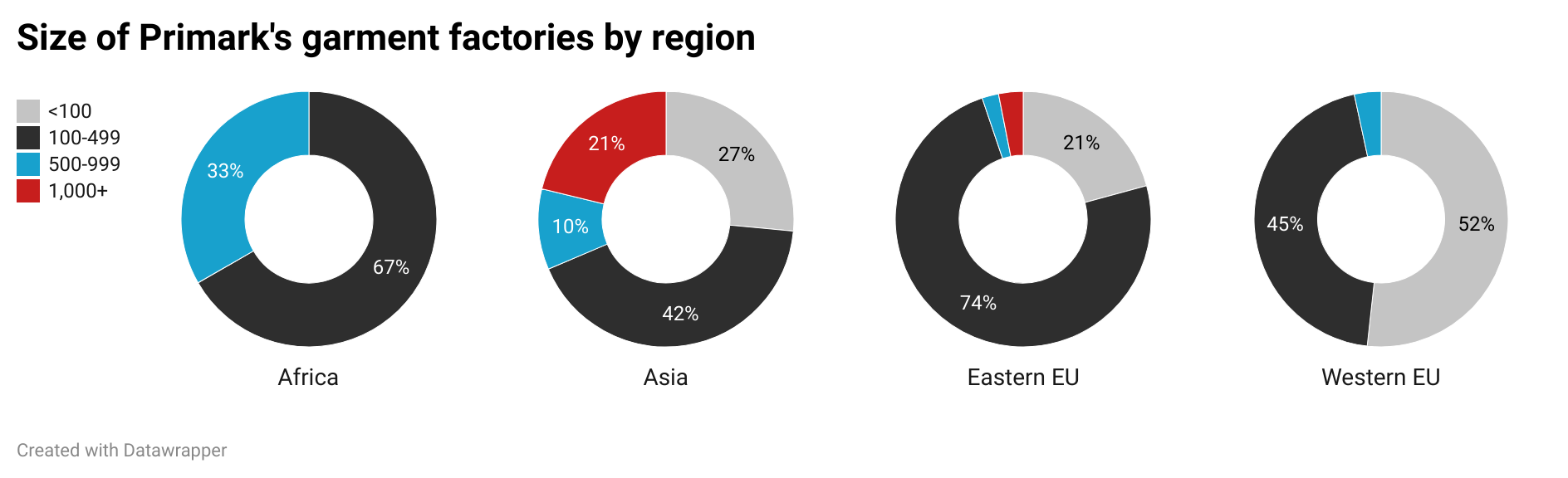

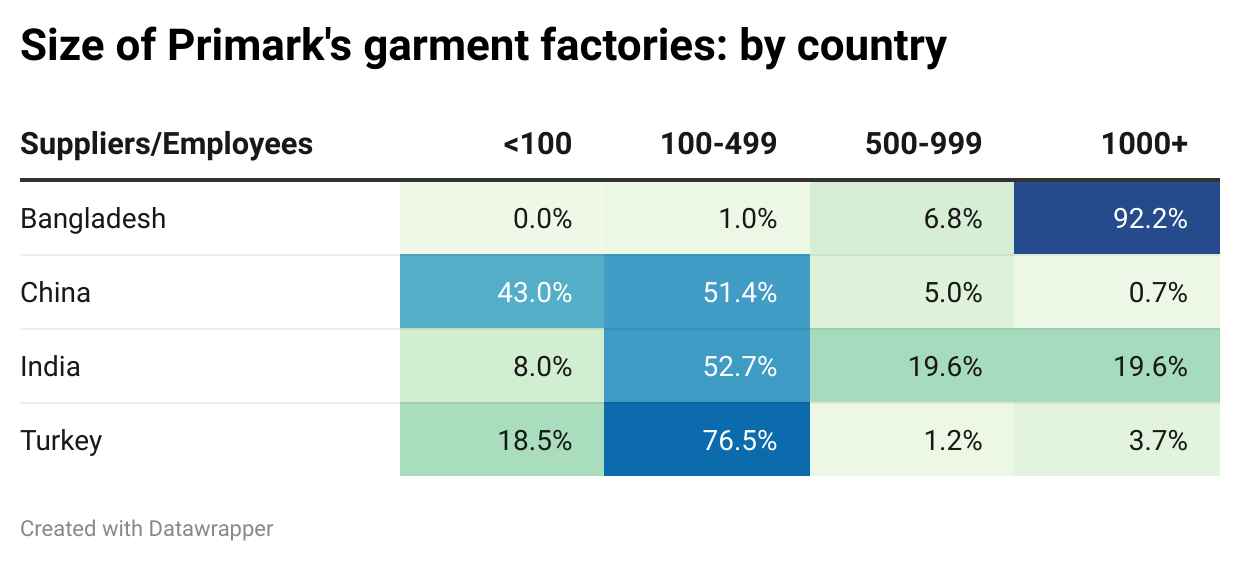

Firstly, aligned with trade statistics, many U.S. fashion companies already source from India, although in a relatively small volume. For example, the USFIA benchmarking survey respondents consistently ranked India as the 3rd or 4th most utilized apparel sourcing base from 2021 to 2024, after China and Vietnam. However, U.S. fashion companies typically place less than 10 percent of their total sourcing value or volume in India. The recent USITC study also raised concerns that India’s apparel factories were primarily small and medium-sized, which could limit their ability to fulfill large-volume sourcing orders.

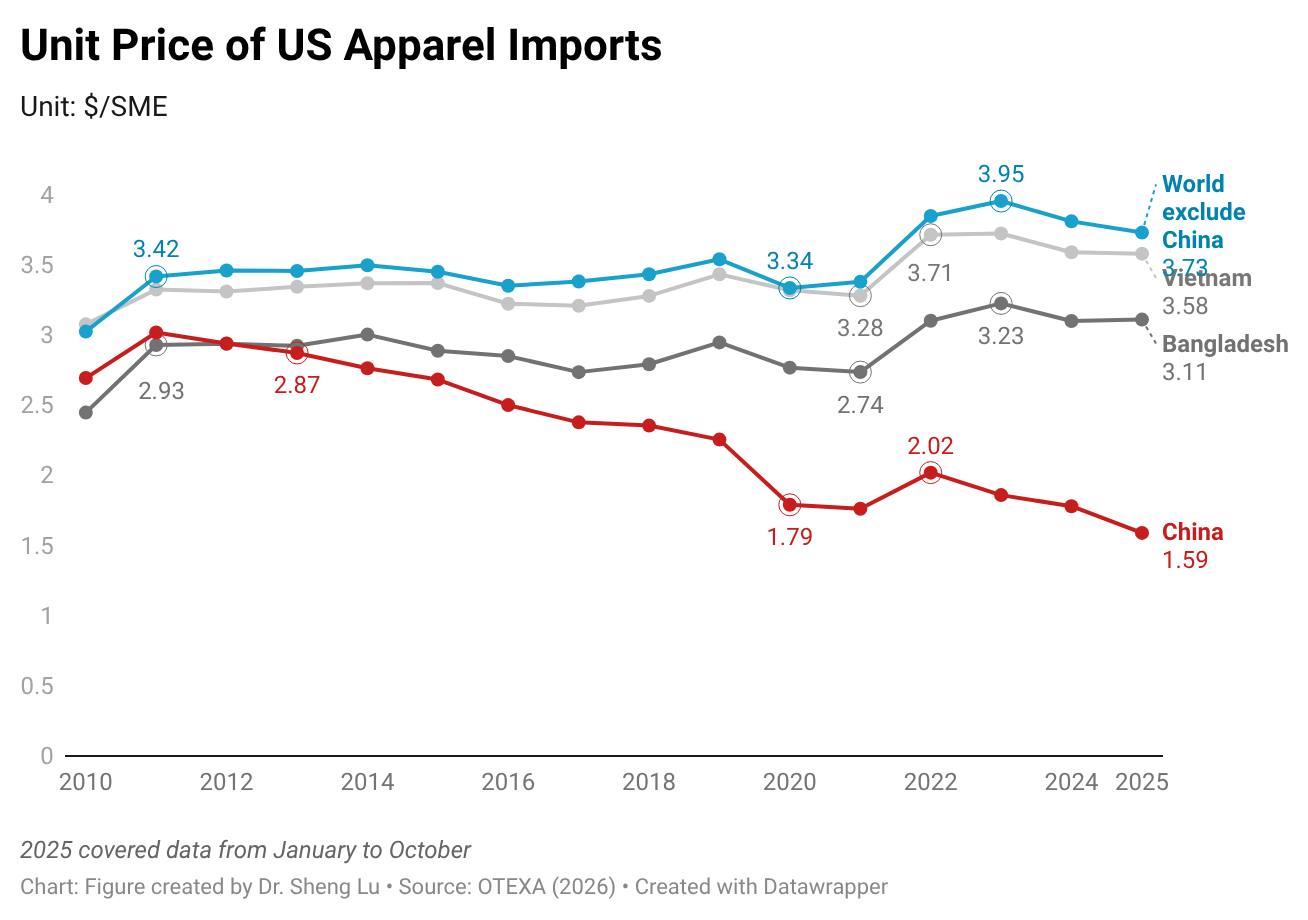

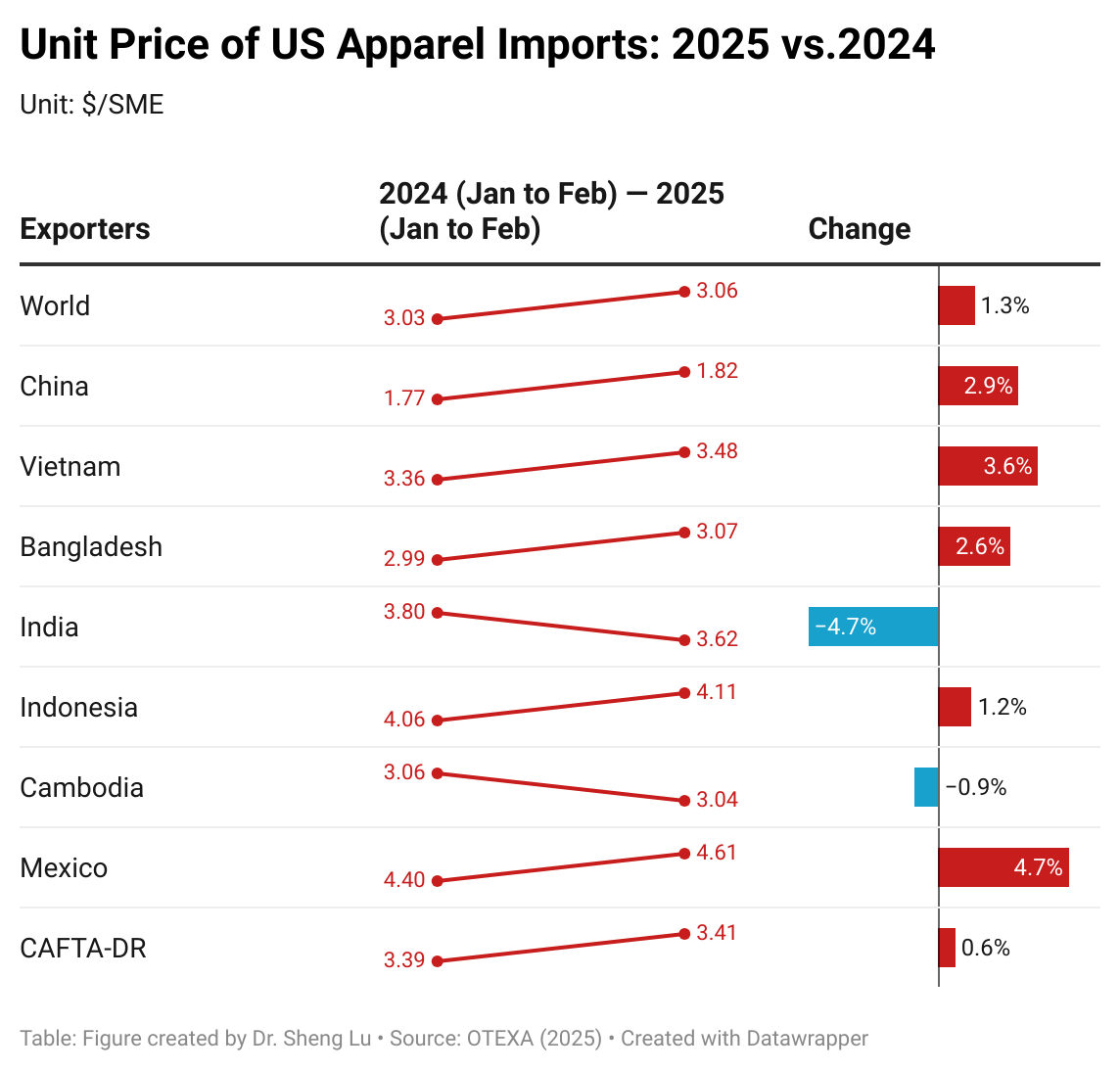

Secondly, “Made in India” clothing is not necessarily cheap but could be perceived as “worth the value.” Notably, from January to October 2024, clothing labeled “Made in India” sold in the U.S. retail market was, on average, priced much higher than imports from Bangladesh and Vietnam, particularly in the mass market segment. Meanwhile, in the premium market segment, clothing “Made in India” was, on average, priced relatively lower than “Made in China,” such as dresses, tops, and bottoms. These results suggest that U.S. fashion companies do not typically consider India a preferred sourcing base for basic and price-sensitive items. Instead, India may be seen as a more cost-effective alternative to China for high-quality, value-added clothing.

Thirdly, India has been strengthening its competitiveness in export flexibility and agility, enabling its vendors to quickly adjust the delivery, volume, and product of the sourcing order upon customers’ requests. In the latest 2024 USFIA survey, respondents rated India’s sourcing flexibility and agility second only to China, surpassing Bangladesh, Cambodia, and Central American countries. Likewise, India was regarded as one of the few Asian countries that could fulfill apparel sourcing orders with relatively low “minimum order quantity (MOQ)” requirements.

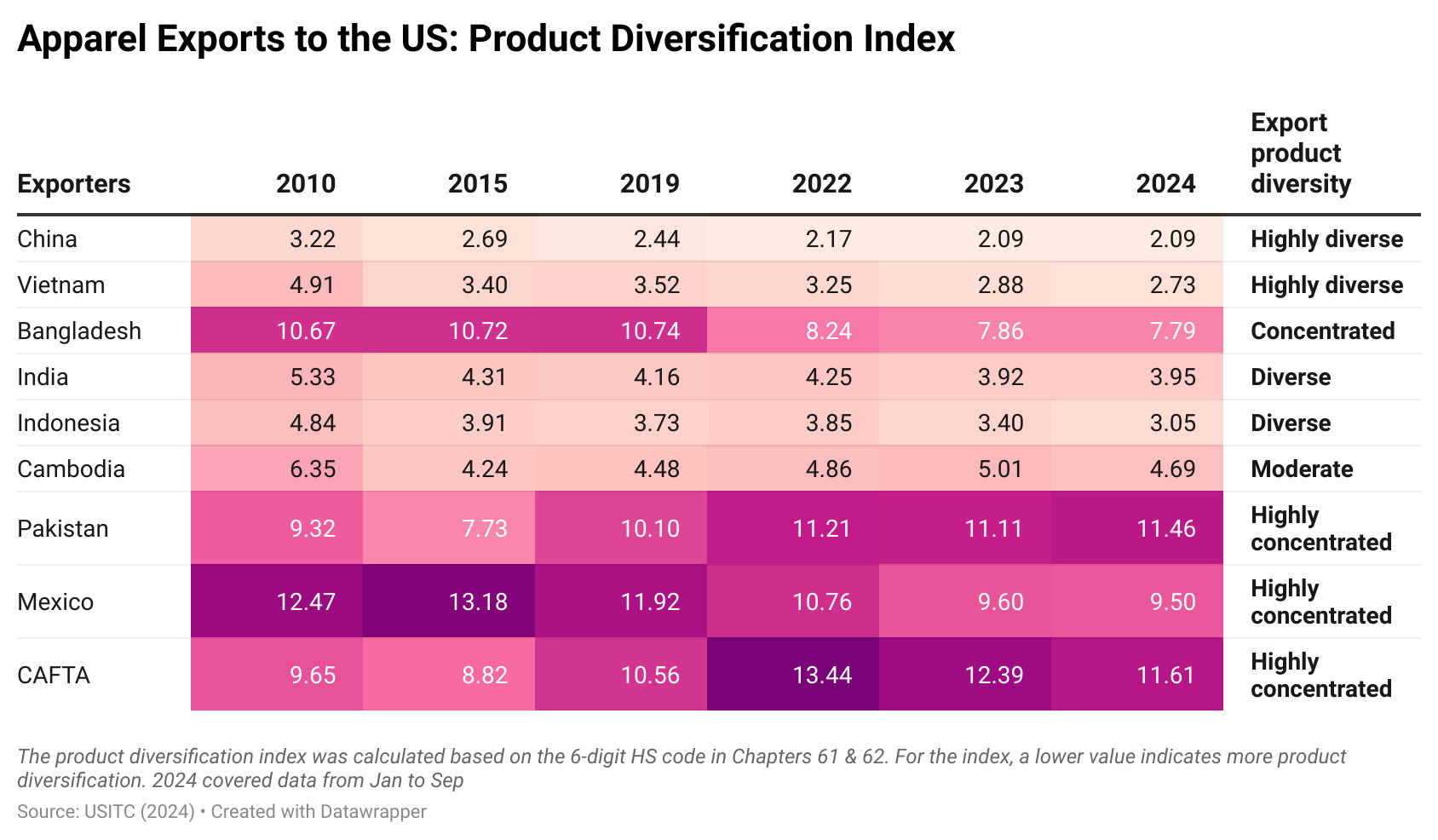

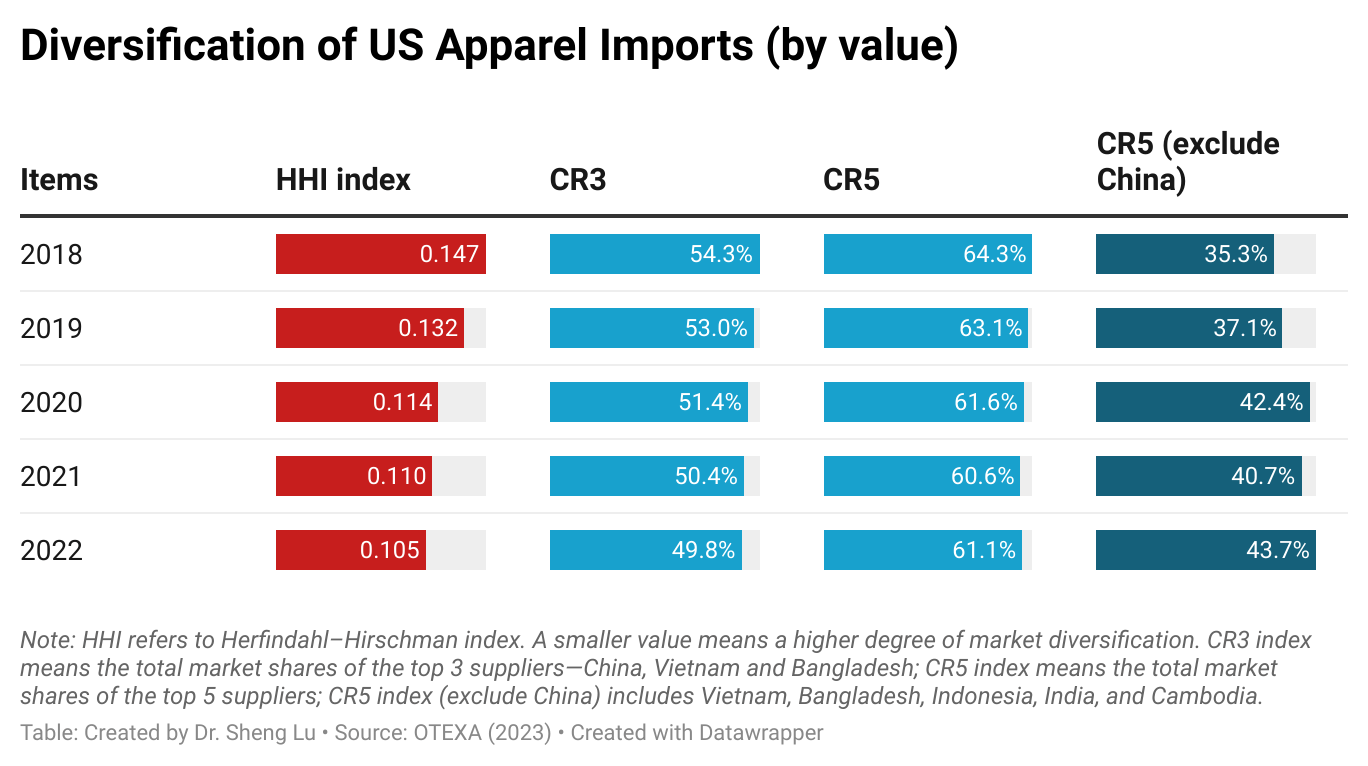

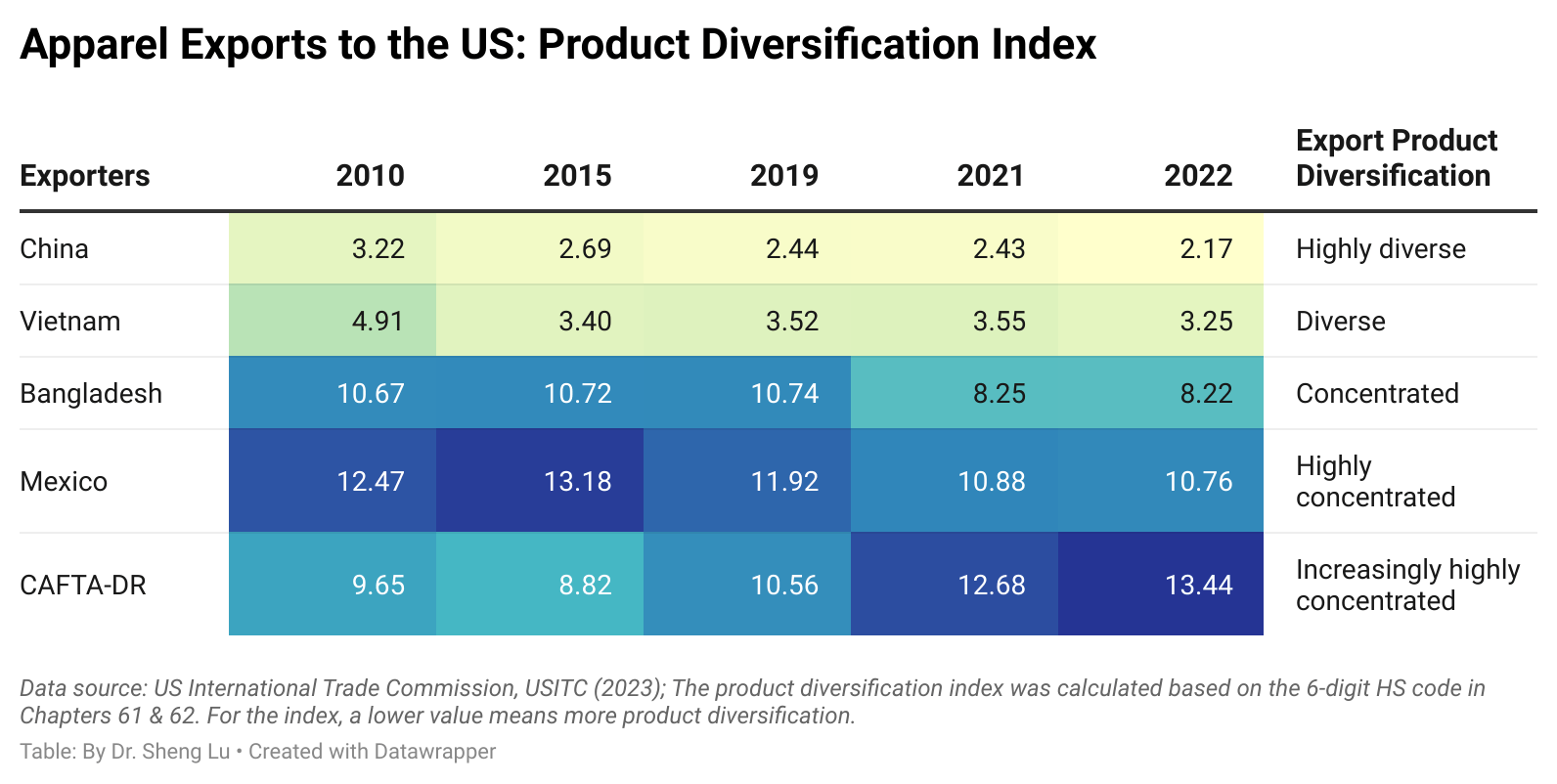

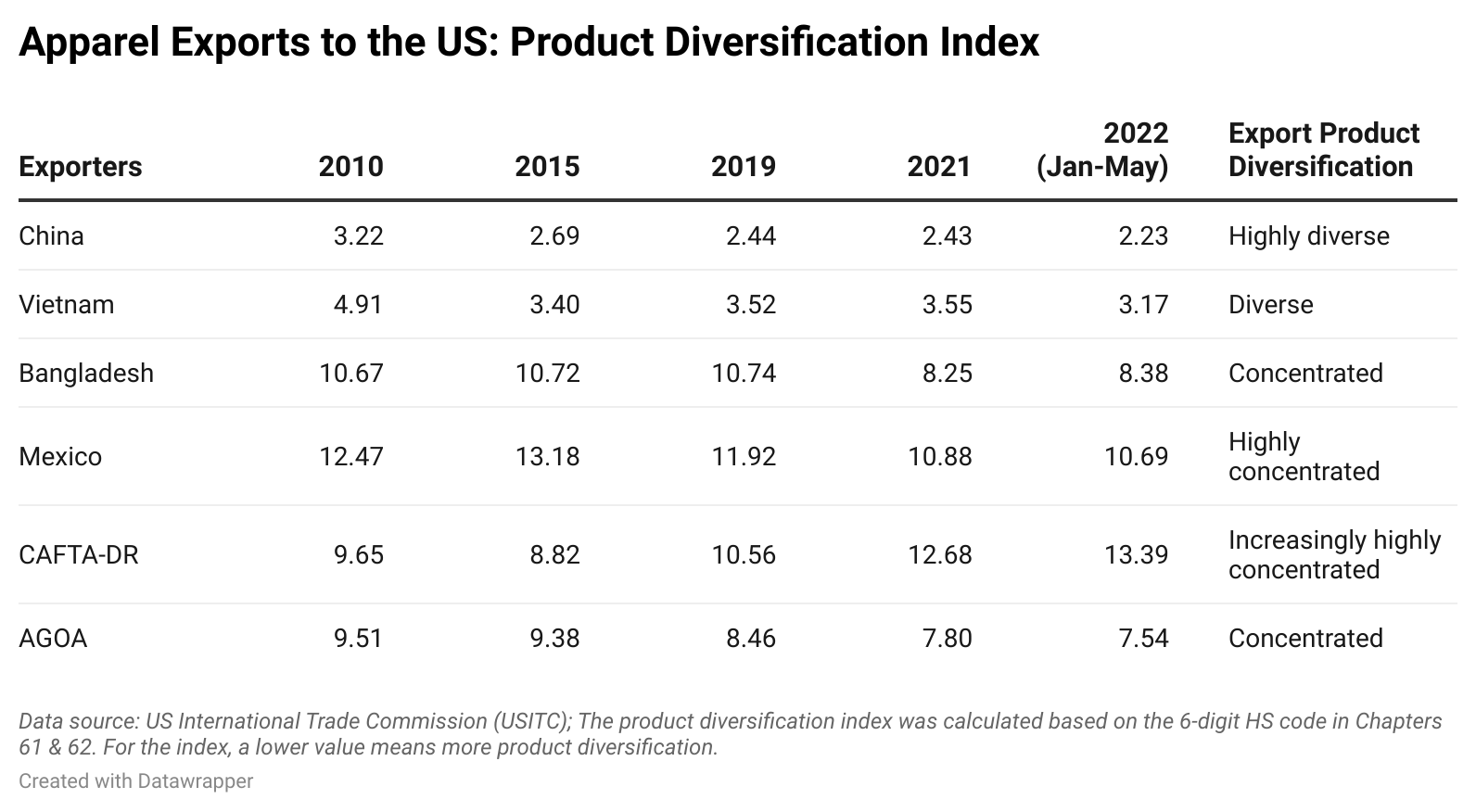

One major factor contributing to India’s perceived advantages in sourcing flexibility and agility is its ability to produce a wide range of apparel products. For example, the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) calculated using trade data at the 6-digit HS code level indicates that U.S. apparel imports from India cover more diverse product categories than most Asian countries.

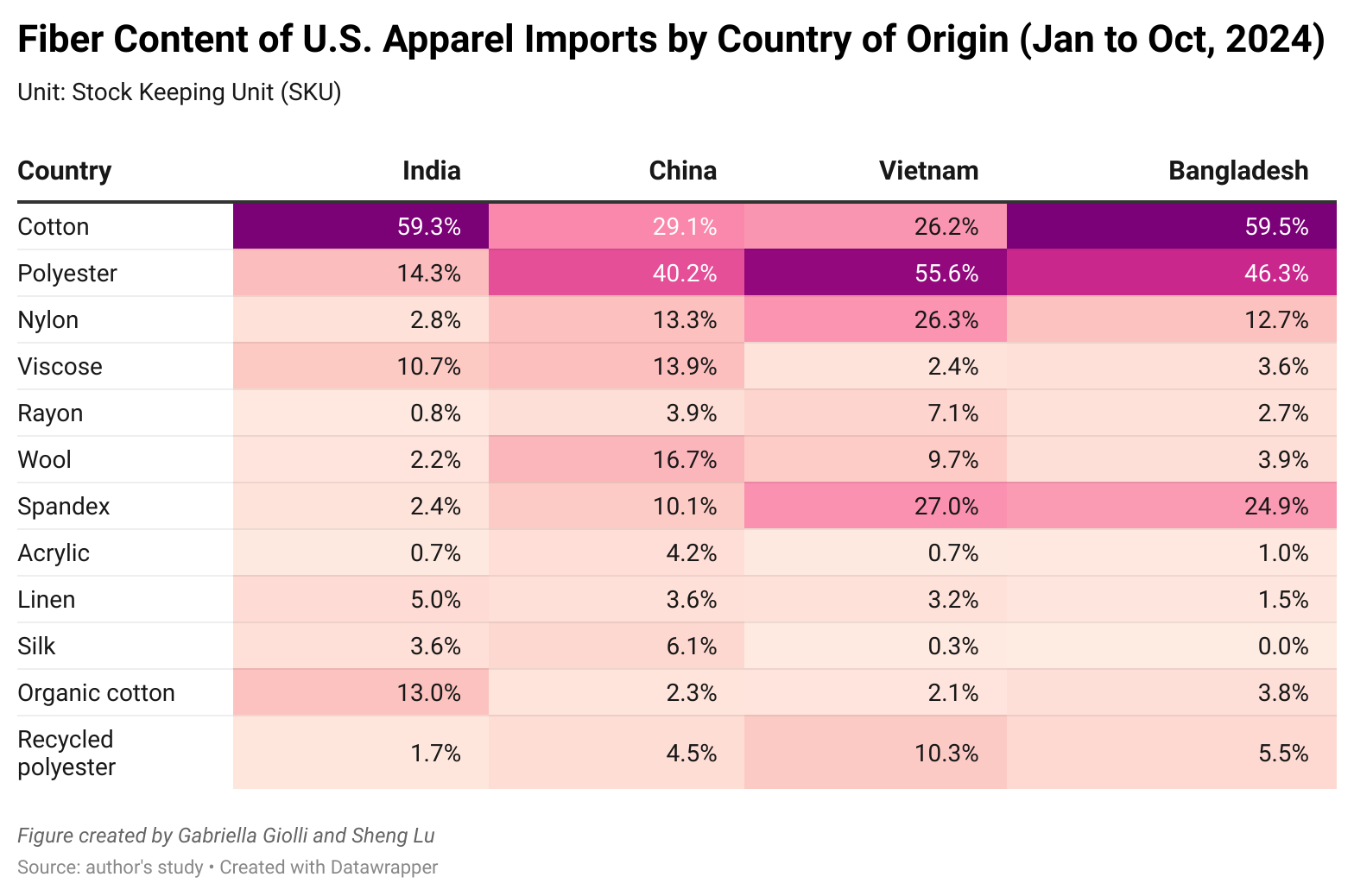

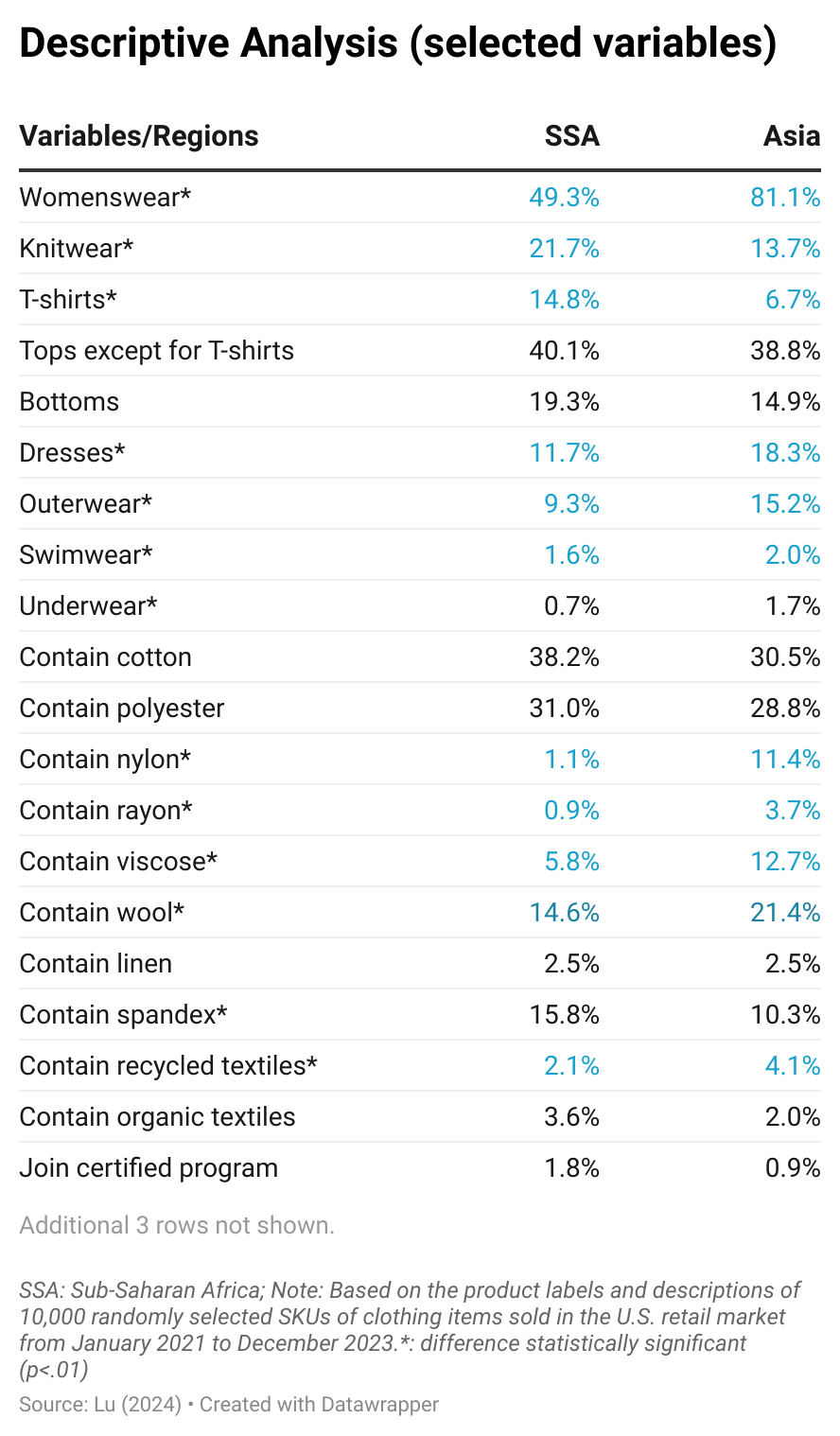

Moreover, due to India’s position as one of the world’s leading cotton producers, in the first ten months of 2024, nearly 60 percent of U.S. apparel imports from India contained cotton fibers, including 13 percent using organic cotton. This percentage was much higher than imports from other Asian suppliers such as China and Vietnam. In comparison, over the same period, U.S. apparel imports from India appear less likely to contain man-made fibers like polyester, nylon, spandex, and recycled polyester. This fiber composition explains why India has yet to become a leading supplier of certain apparel product categories, like outerwear, which more commonly uses man-made fiber than cotton.

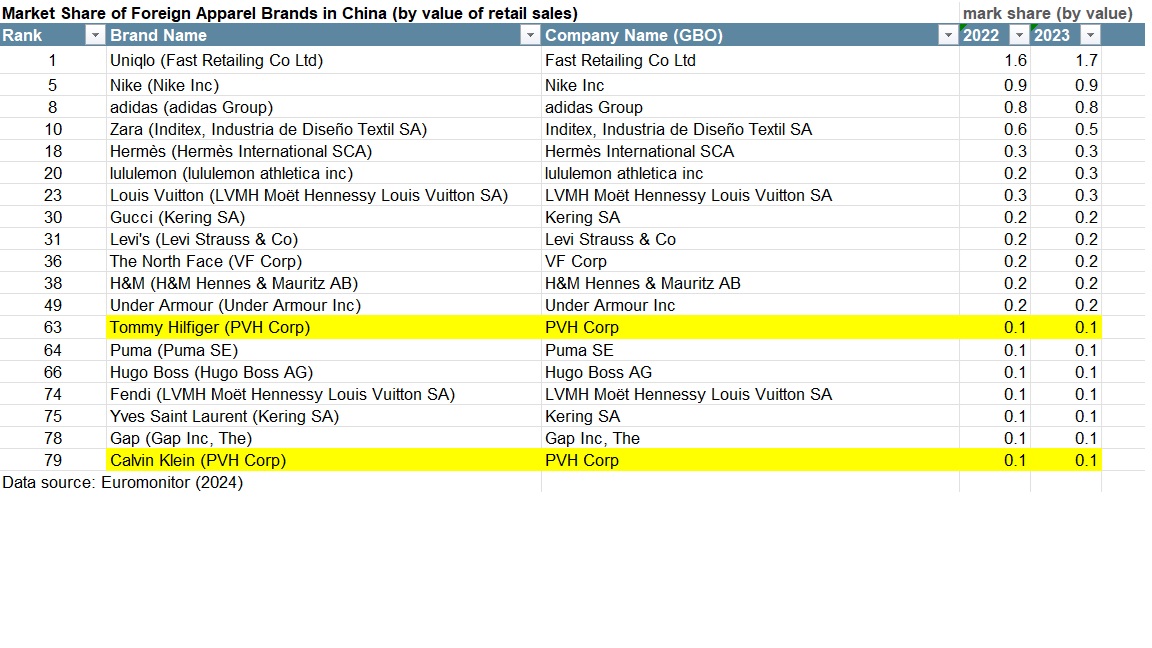

Additionally, in the first ten months of 2024, over 45 percent of India’s apparel newly introduced to the U.S. market targeted the luxury and premium segment, closely matching China’s nearly 50 percent and exceeding other Asian suppliers such as Vietnam (20 percent), Bangladesh (13 percent), Cambodia (5 percent), and Indonesia (18 percent). This result explains why U.S. fashion companies increasingly consider India a strategic alternative to sourcing from China, given the similarities in their product offerings.

Reflections

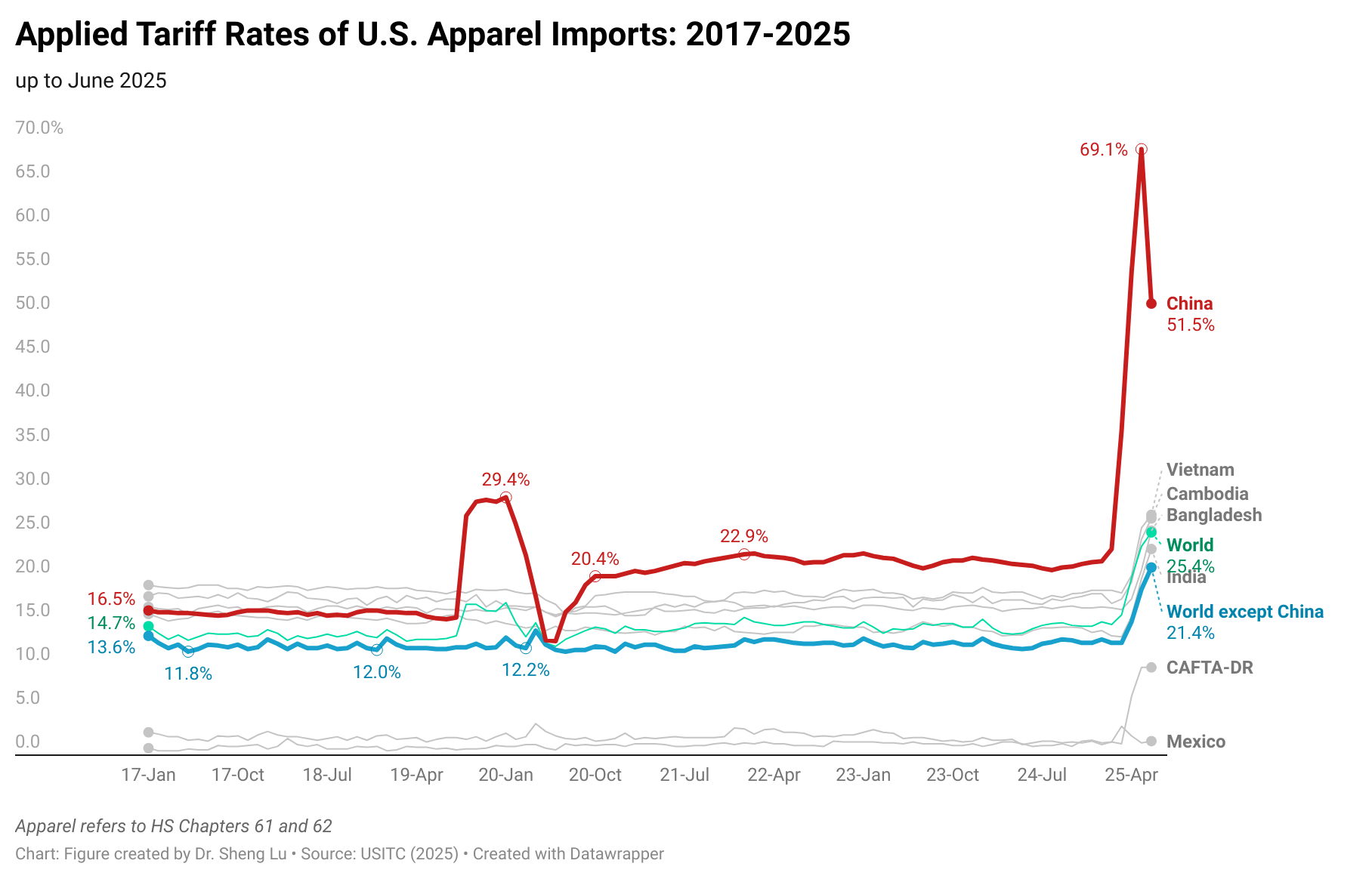

India’s large country size and population, the presence of an already highly integrated and sophisticated textile and apparel supply chain, and its ability to make a great variety of high-quality products suitable for various market segments position it well in the export competition. U.S. fashion companies’ eagerness to reduce sourcing from China due to rising geopolitical concerns and the limited sourcing capacity elsewhere created historical opportunities for India to expand its apparel exports to the U.S. market further.

Nevertheless, it remains a question mark whether India is fully committed to expanding labor-intensive apparel production and exports, given the country’s economy is moving toward more capital and technology-intensive sectors. Notably, in value, apparel only accounted for about 5.6 percent of India’s total merchandise exports in 2023, similar to China’s 5.3 percent but much lower than other lesser-developed Asian countries, including Vietnam (10 percent), Bangladesh (88 percent), and Cambodia (44 percent).

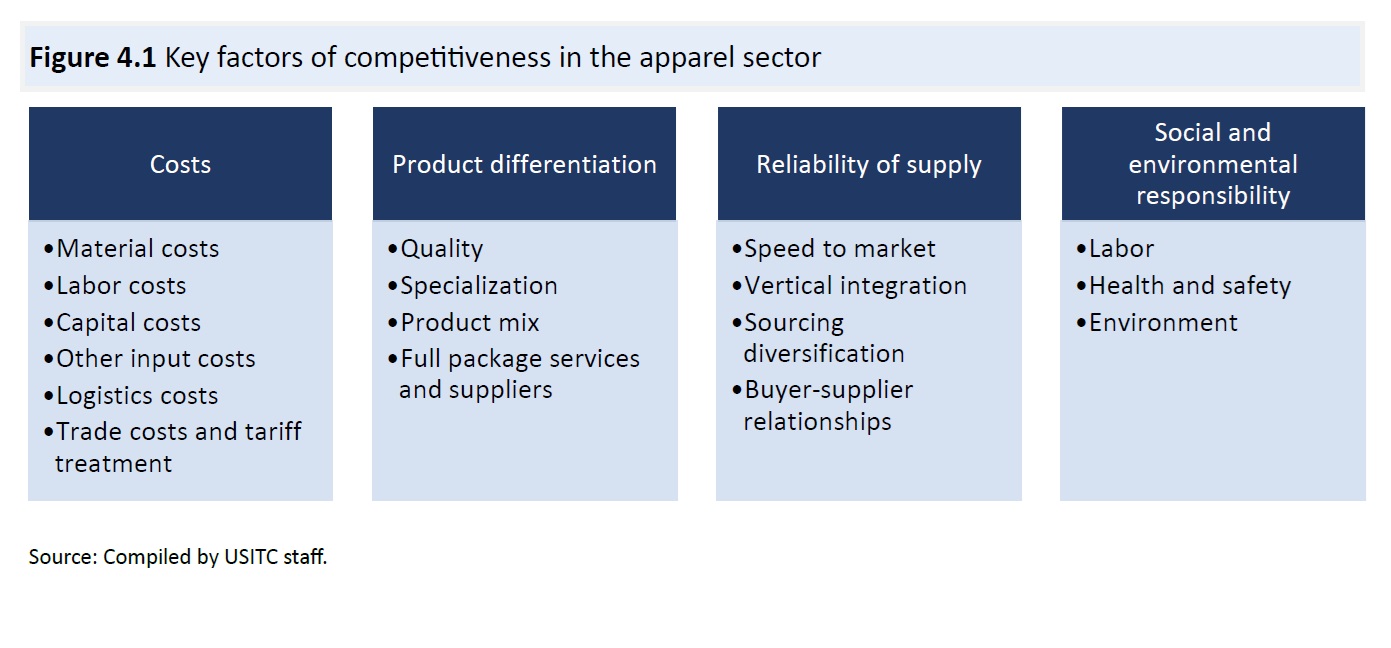

Moreover, while India is not a primary focus for compliance issues like forced labor, sourcing from the country still carries general social and environmental compliance risks similar to those in most developing countries (note: see the 2024 USITC report). It remains to be seen whether India’s textile and apparel mills are technically and financially prepared to meet more stringent social and environmental standards being adopted in the U.S. and can effectively compete in the growing market for “sustainable apparel.”

by Gabriella Giolli (Honors Marketing major & Fashion management minor, University of Delaware) and Sheng Lu