While the majority of apparel consumed in the United States come from overseas, “Made in the USA” is growing in popularity. According to the 2018 U.S. Fashion Industry Benchmarking Study released by the U.S. Fashion Industry Association (USFIA) in July 2018, around 46 percent of surveyed U.S. fashion brands and apparel retailers report currently sourcing “Made in the USA” products, even though local sourcing typically only account for less than 10 percent of these companies’ total sourcing value or volume. Likewise, the State of Fashion 2019 report published by Business of Fashion (BOF) and McKinsey & Company in November also forecasts that over 20 percent of U.S. fashion companies’ sourcing volume could be from nearshore by 2025, thanks to automation technology and consumers’ increasing demand for speed to market.

However, the detailed practice of the “Made in the USA” apparel sourcing strategy–including who is sourcing, what products are sourced, and what the typical price range of these products remain largely unknown.

To answer these questions, we recently analyzed the pricing, product assortment and inventory information of over 90,000 fashion retailers and 300,000,000 fashion apparel products at the Stock-Keeping Unit (SKU) level based on EDITED, a big data and business analytics tool developed for the fashion industry. For the research purpose, we selected apparel products newly launched to the U.S. market in the past twelve months (i.e., between 1 December 2017 and 30 November 2018) with “Made in the USA” explicitly mentioned in the product description. Below are the key findings:

First, “Made in the USA” apparel overall are treated as a niche product in U.S. fashion brands and retailers’ sourcing portfolio.

During the 12 months we examined (1 December 2017-30 November 2018), 94 out of the total 348 retailers (or 27 percent) sold “Made in the USA” apparel in the U.S. market. The top 10 sellers list includes BOTH retailers that focus on the value market such as Walmart and relatively high-end department stores such as Bloomingdale and Saks Fifth Avenue. However, even for these top sellers, “Made in the USA” apparel accounted for less than 8 percent of their total product offers on average.

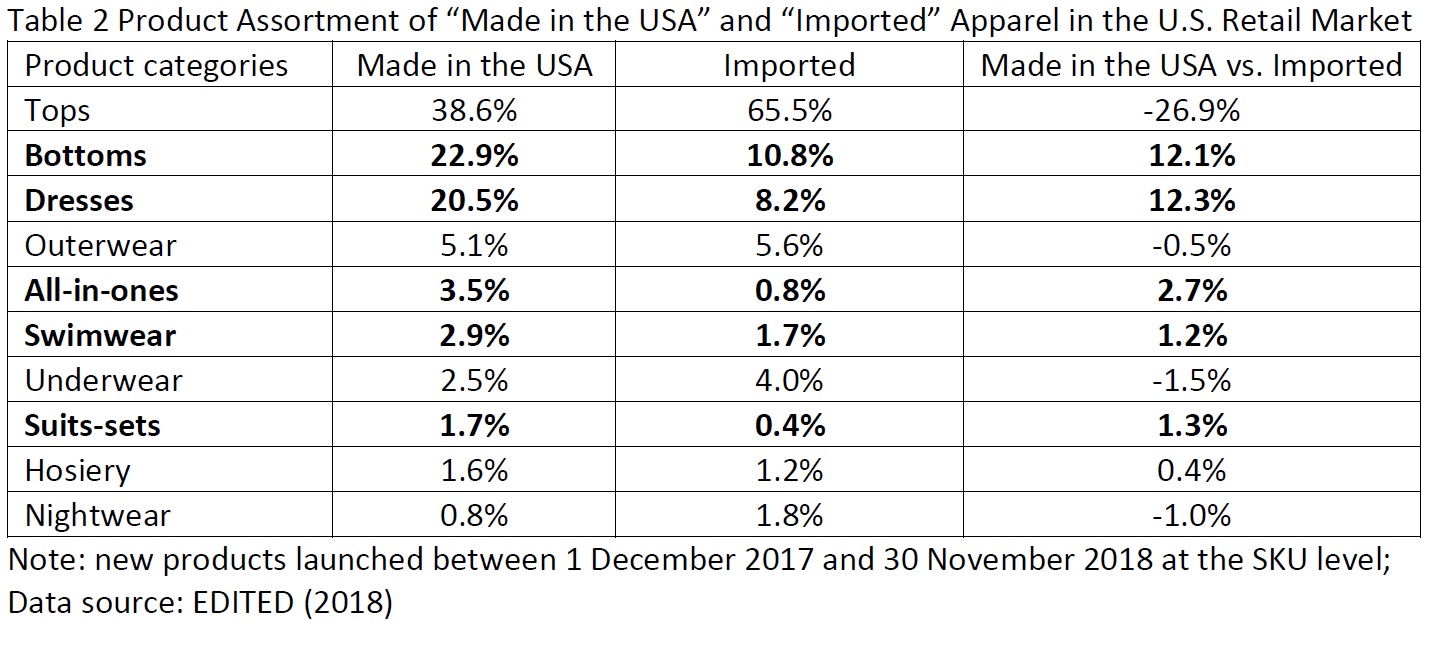

Second, U.S. fashion brands and retailers are most likely to source“Made in the USA” apparel for relatively fashion-oriented items, particularly bottoms (such as skirts, jeans, and trousers), dresses, all-in-ones (such as playsuits and dungarees), swimwear and suits-sets.

The competitive edge for these product categories in the retail market, in general, increasingly depends on unique designs, high product quality, and speed to market, which makes sourcing from the United States commercially beneficial. In comparison, imported products are more concentrated on basic fashion items often competing on price in the U.S. retail market, including tops (such as T-shirt and polo shirt), underwear, and nightwear.

It is also interesting to note that “Made in the USA” apparel were predominately women’s wear (92 percent), whereas imported clothing adopted a more balanced gender combination (63 percent women’s wear and 37 percent men’s wear). Because the fashion trends for women’s wear usually are shorter-lived and harder to predict, this result once again indicates that seeking quick response and shorter lead time for stylish and trendy items could be an important incentive for local sourcing by U.S. fashion brands and retailers.

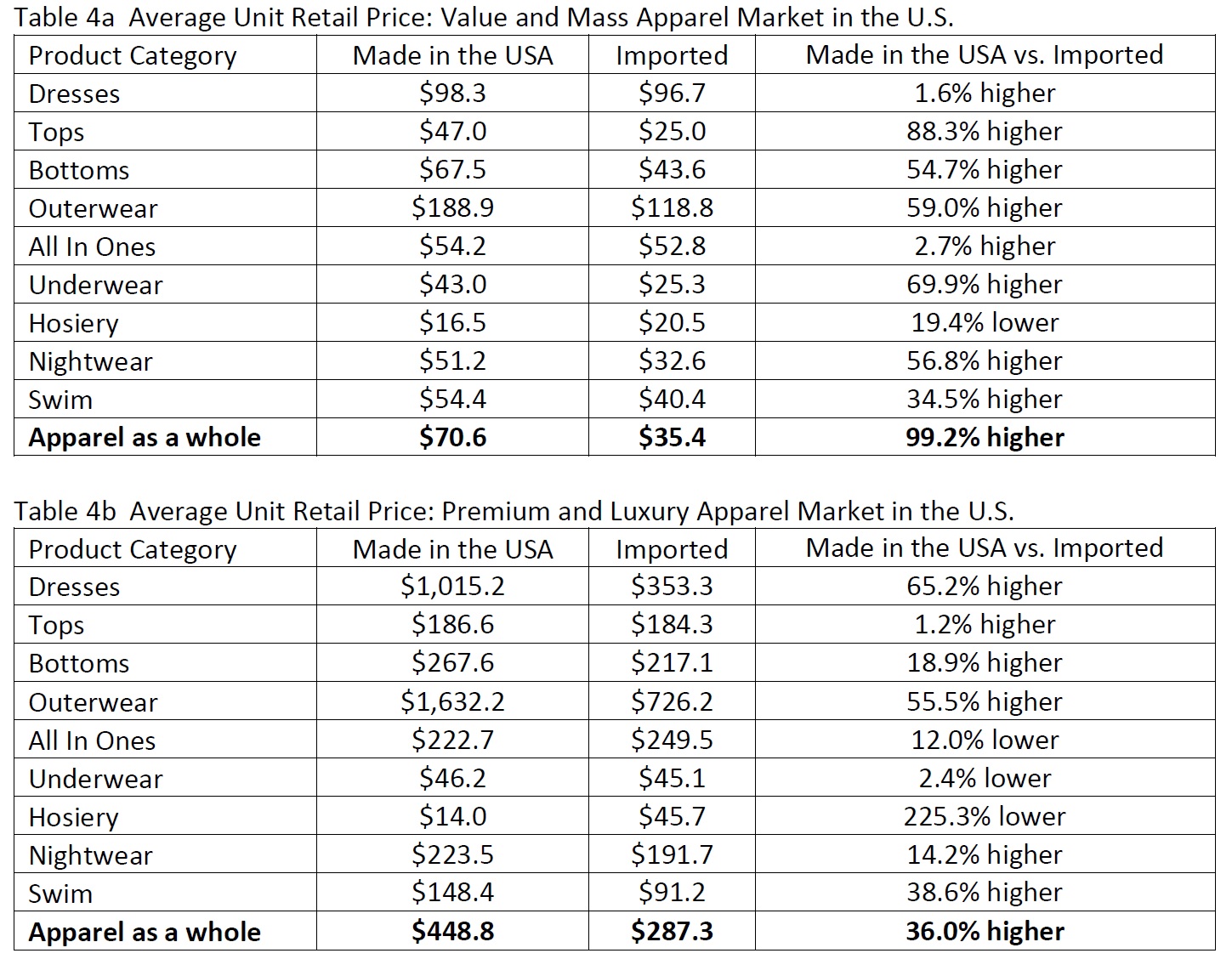

Third, consistent with the common perception, “Made in the USA” apparel overall are pricier than imported ones in the U.S. retail market.

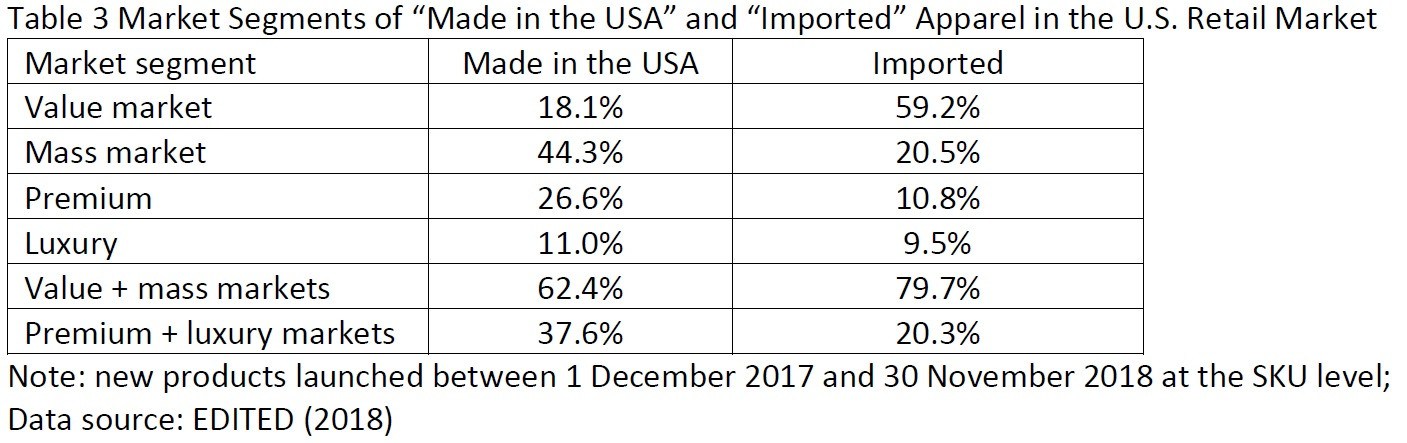

Taking the U.S. apparel retail market as a whole, close to 40 percent of “Made in the USA” offering in the past 12 months targeted the premium or luxury market, compared with only 20 percent of imported products. In contrast, as few as 18 percent of “Made in the USA” offering were in the value market, which, however, accounted for approximately 60 percent of all imported apparel sold in the U.S. market. In totality, it seems U.S. fashion brands and retailers are purposefully targeting “Made in the USA” apparel for less price-sensitive segments of the market to balance the high domestic production cost.

On the other hand, when examining U.S. fashion brands and retailers’ pricing strategy at the product level, “Made in the USA” clothing was still priced much higher than imported ones for almost all major apparel categories, except hosiery. Notably, in the past 12 months, the average unit retail price of “Made in the USA” clothing was 99.2 percent higher than imported ones in the value and mass market and 36.0 percent higher in the premium and luxury market. This interesting phenomenon supports the arguments that U.S. consumers somehow are willing to pay a premium price for products with the “Made in the USA” label.

Additionally, during the past 12 months, around 46.3 percent of “Made in the USA” apparel were sold at a discount compared with more than 54.6 percent of imported ones. The advantage of proximity to the market, which makes speedy replenishment for in-season items possible, is an important factor behind the more successful control of markdowns for “Made in the USA” products. For example, data shows that U.S. fashion brands and retailers replenished approximately 12.7 percent of their “Made in the USA” offering in the past 12 months but only 2.8 percent of imported clothing.

In conclusion, the findings of this study concur with the view that “Made in the USA” apparel are still relevant today. Meanwhile, it does not seem to be the case that “Made in the USA” apparel and imported ones are necessarily competing with each other in the U.S. retail market. With apparel sourcing increasingly requiring striking a balance among various factors ranging from cost, flexibility, compliance to speed to market, it is hopeful that “Made in the USA” apparel will continue to have its unique role to play in U.S. fashion brands and retailers’ merchandising and sourcing strategies.

By Sheng Lu