About Natalie Kaucic

Natalie Kaucic is a Merchandising professional currently in the role of Global Merchant for Dockers Men’s Tops at Levi Strauss & Co. She graduated from the University of Delaware in 2019 with a Fashion Merchandising Degree and Business Admin minor. During her studies, she was awarded the Fashion Scholarship Fund scholarship, studied at John Cabot in Rome, participated in the Disney College Program, and was a leader for the Delaware Diplomats. Natalie’s research on the global market for sustainable apparel was published in Just-style, a leading fashion industry trade publication. Post university, Natalie started as an assistant at Minted as a Merchandiser, where she worked in the Wedding category and faced the adverse challenges of the wedding industry during COVID-19. Levi’s was her next endeavor where she started as an assistant, and has since been promoted to run the Dockers Men’s Tops Category for the Globe.

Disclaimer: The comments and opinions expressed below are solely my own and do not reflect the views or opinions of any company.

Sheng: What are your primary job responsibilities as a global merchant? What does a typical day or week look like for you? Which part of the job do you find most exciting? Were there any aspects of the position that surprised you after you started?

Natalie: My primary responsibility is to create a brand-right and consumer-focused product assortment. Under the covers, this looks like a vast variety of tasks that I do on a seasonal basis. I regularly listen and work with regional merchandising to understand their regional specific needs, collaborate with design on new product ideas and fabrics, and meet with product development to work on new fabric innovations and product costing. Every week looks dramatically different for me in my work. Sometimes, I’m heads down in assortment strategy; other weeks, I work on creating templates and calendars for process improvement.

What I find most exciting is seeing the product in person. Most Dockers Tops are not sold domestically, so it’s really fun to see a product you worked on in the wild! I am also grateful to be able to manage an assistant. Seeing things click for her and watching her succeed is incredibly motivating.

What surprised me the most was the number of different teams I work with, including planning, regional merchants, product development, marketing, styling, design, garment/fit development, copy, IT, analytics, sales, business operations, and e-commerce. Learning what everyone does and who to go to was the most significant learning curve and the biggest shock coming into my role.

Sheng: Based on your observation and experience, how do the merchandising, product development, and sourcing teams collaborate in a fashion apparel company? Could you explain their respective responsibilities and how they support one another?

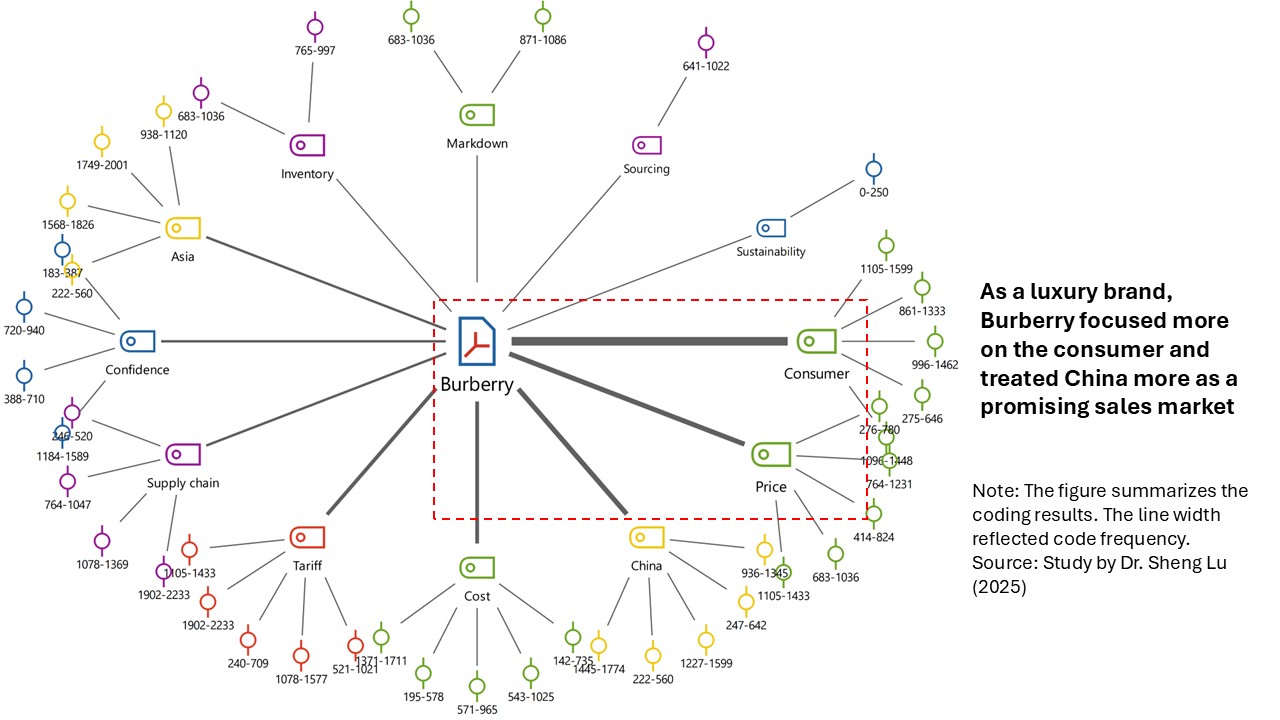

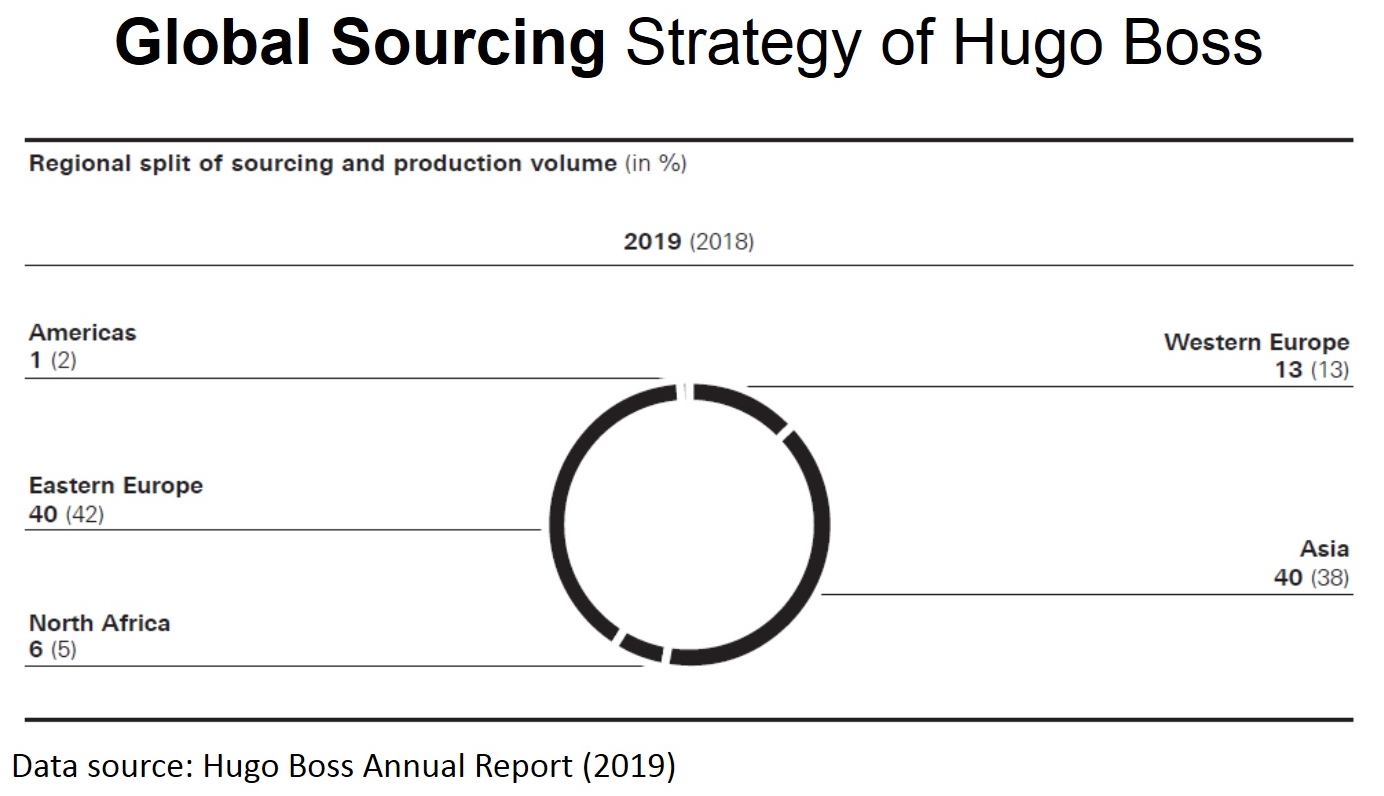

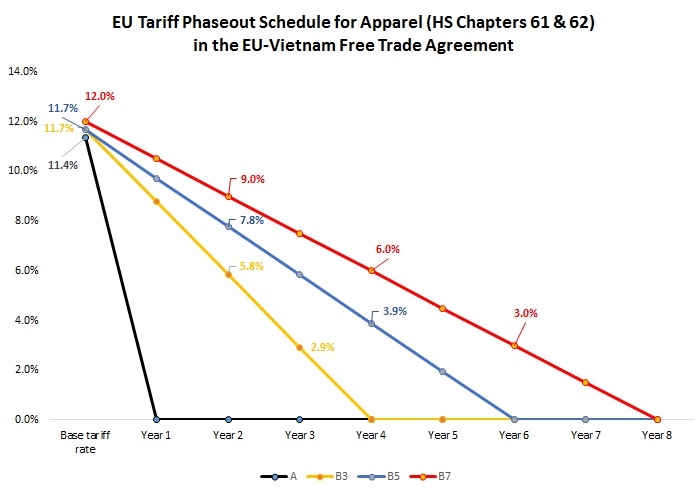

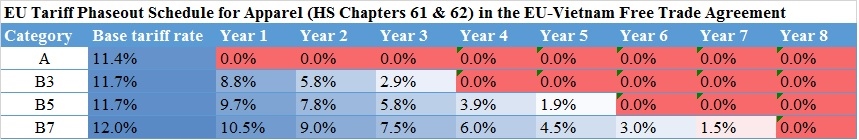

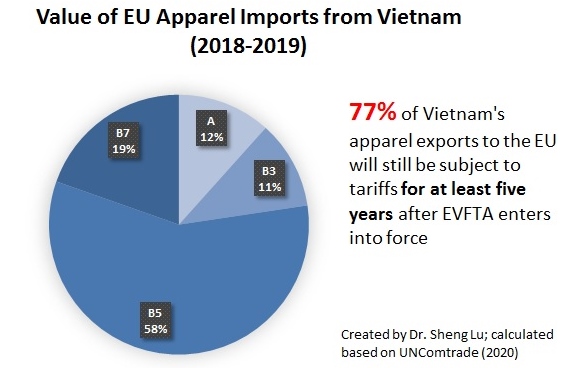

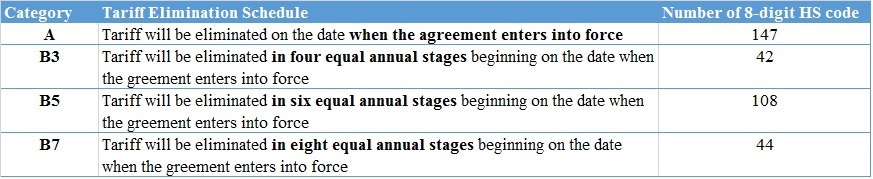

Natalie: In my role, I have more direct contact with our product development team than the sourcing team. I work very closely with product development as they are the team that helps produce our product. They manage fabric & garment development, costing negotiations, and innovation development/testing. They also work through some more micro-sourcing strategies, for example, moving the production from one factory to another to get better duty rates. As a hypothetical example, we sell a poplin shirt primarily in Europe. Pretend we produce the shirt in India at a cost of $10/each. However, shipping it to Europe incurs a 40% import duty, bringing the cost of goods sold (COGS) to $14. If we could produce the shirt in Mexico, where the duty rate to Europe is only 5%, even if the production cost is higher—say $12—the overall cost to Europe would still be lower. There are endless complexities to this that I’m sure you will learn more from FASH455—topics like free trade agreements, yarn forward rules of origin, etc.

Sheng: Fashion companies need to balance various factors such as cost, quality, speed to market, and compliance risks when deciding where to source their apparel products. Could you share your experiences and reflections on managing these challenges in the real world?

Natalie: Below is an example of natural fibers and the cost challenge with cotton-forward apparel products.

Currently, linen is in high demand, but there isn’t enough crop to meet industry needs—it’s a classic case of supply and demand. Not only does this drive up costs (COGS), but it also complicates the process of securing raw materials. It’s easy to overlook that the apparel industry is fundamentally tied to agriculture, making it vulnerable to factors like bad weather, natural disasters, and inaccurate demand forecasting. These challenges force us to make critical decisions. With rising garment costs, should the company absorb the expense to keep prices steady for consumers? Our product development team might ask if we need to pre-book fibers to lock in pricing—when is the right time to do that, and how much should we purchase?

This isn’t a new challenge. For example, cotton, our primary raw material for clothing, fluctuates in price like oil, making agility in sourcing essential!

Sheng: Studies show that consumers want to see more “sustainable apparel products” in stores. How are fashion companies responding to this demand? What opportunities and challenges does this trend present for fashion companies’ business operations, especially in merchandising, supply chain, and sourcing?

Natalie: This is such a complicated question. I think about this often as I am personally really passionate about this topic!

In my day-to-day work, I focus on sustainable fibers, as the fabric content of a garment is something I can directly influence. Working on a global scale, I collaborate with regions worldwide, each of which—along with their retailers—has different values regarding sustainable products. Europe, for instance, is relatively ahead of the US in sustainability and often requires a certain percentage of sustainable fibers (e.g., organic cotton, recycled cotton) in our products. In Europe, items using 100% organic cotton hold significant value and can command a higher price in stores such as Galeries Lafayette or Zalando. However, not all retailers and consumers globally share the same commitment to sustainability. In some cases, we may need to use synthetics for functional purposes, such as in activewear. In those instances, we prioritize using recycled polyester or nylon to meet our sustainability goals. Regardless of the consumer or price point, our goal is to integrate sustainability at every level and for every product.

One challenge I find particularly interesting is working with “recycled cotton.” As you may know, recycling cotton typically involves breaking down the fibers, which shortens and weakens them. Because of this, there’s usually a limit to how much recycled cotton can be used before fabric quality is affected. That’s why you often see recycled cotton blended with virgin cotton in the same garment. However, newer recycling methods that aim to preserve the staple length are emerging, offering hope for improvements as the technology becomes more mature and accessible.

Ultimately, heavy consumption, regardless of the fabric being recycled or organic, isn’t truly sustainable. The focus should be on choosing pieces you love and investing in items that are made to last.

Sheng: Are there any other major trends in the fashion industry that we should closely monitor in the next 1-3 years?

Natalie: In the next 1-3 years, I’m eager to see what AI-driven tools will be introduced to assist merchants in making smarter, data-backed decisions. In merchandising, we are constantly trying to predict the future. A lot of research and data analysis go into decision making, but also a big handful of going with your gut. Will AI be able to help us find trends in the past that can better help us make decisions for the future?

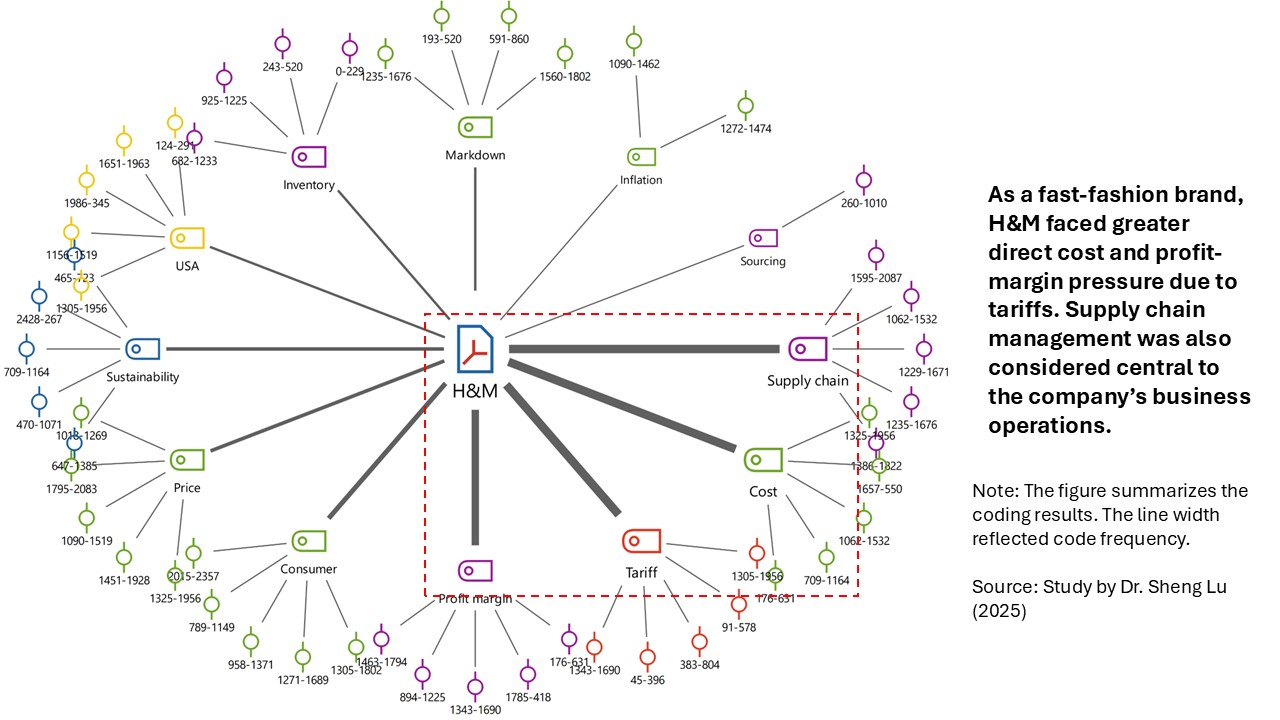

It’s not exactly a trend, but I’m really curious about the future of fast fashion giants over the next decade. With growing interest in sustainability and new regulations emerging from Europe, will we eventually see a decline in these dominant players, or will demand for fast, cheap apparel always persist?

Sheng: Last but not least, is there anything you learned from FASH455 or other FASH courses that you find particularly relevant and helpful in your career? What advice would you offer current students preparing for a career in the fashion apparel industry?

Natalie: I felt really prepared coming out of the FASH program for my corporate job. I picked this degree, as I’m sure many have because it combined the necessary key concepts of a business degree with the skills and knowledge to build a career in apparel. I think the classes I reference the most in my day-to-day life are product development classes, textile classes, and apparel buying. As a merchant, I need to be able to talk about fabric types with designers, cost engineering with product developers, and financial metrics with planners. FASH455 was one of my favorite classes because sourcing, trade, geopolitics, and policy constantly pull the strings behind the scenes in the apparel sector. FASH455 gives you insight into how these factors create ripples in the apparel sector.

When it comes to advice, it’s tried and true: network! Talk to teachers, reach out to alumni, sign up for the UD Job Shadow Program, and talk to the career center. There are so many services to take advantage of while at UD. Other than networking, I would highly recommend steering the subjects of your papers to companies and topics you are interested in. I worked on a few reports about Levi Strauss & Co., which confirmed it as a target company for me and helped me succeed in the interview process.

Lastly, be flexible! You might come in, as I did, thinking you want to be a buyer, only to realize it’s not the best fit. Or, you could start with greeting cards and stationery merchandising and pivot to apparel. Or even move out of apparel entirely! Nothing is set in stone, and that’s both the most stressful yet reassuring lesson I’ve learned since graduating.

–The End–