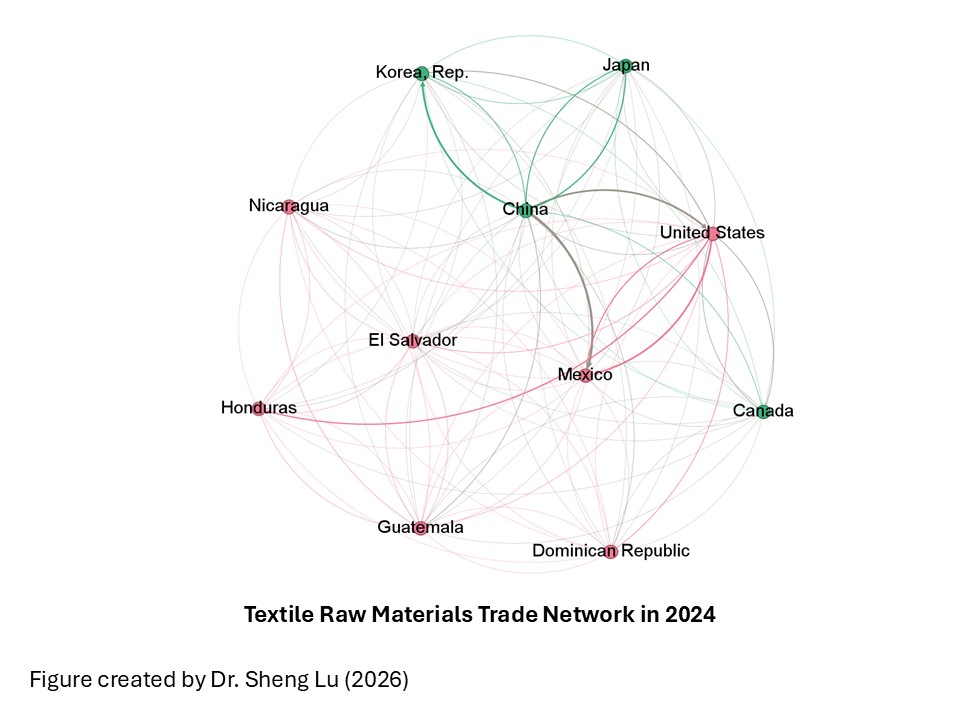

Based on data from UNComtrade, this new study analyzed the evolving patterns of trade in textile raw materials (i.e., yarns, fabrics, and textile accessories*) in the Western Hemisphere from 2010 to 2024. Note: textile raw materials included products under SITC codes 651, 652, 653, 654, 655, and 656. Below are the initial findings:

First, the value of closeness centrality (i.e., how close a country is to all others in the network) consistently exceeded 0.8 for most countries in the Western Hemisphere, including the US and other CAFTA-DR and USMCA members, from 2010 to 2024. This indicates that a highly connected regional network of trade in textile raw materials existed among Western Hemisphere countries during the examined period. However, the closeness centrality results also indicated that Nicaragua, whose closeness centrality score declined from 0.9 in 2015 to 0.83 in 2024, and Honduras, whose score declined from 0.77 in 2015 to 0.67 in 2024, appeared to be relatively “marginalized” in recent years. The result can be attributed to the political and social instability in these countries over the past few years, which has negatively impacted trade.

Second, while the U.S. has been a highly influential and well-connected hub for textile raw material trade in the Western Hemisphere, it is never a “chokepoint.” Specifically, from 2010 to 2024, the U.S. consistently held the highest eigenvector centrality score in the region, confirming its role at the center of the trade network. However, the U.S. betweenness centrality score, measuring its role as a bridge in the trade network, was always low and even declined from 0.033 in 2010 to 0.019 in 2024. Other Western Hemisphere countries showed similarly low betweenness centrality scores. This pattern indicates that CAFTA-DR and USMCA members mostly engaged in direct bilateral trade in textile raw materials rather than routing it through the U.S. as an intermediary. Thus, the U.S. functions as a central trading partner, not a bottleneck, in this regional supply chain.

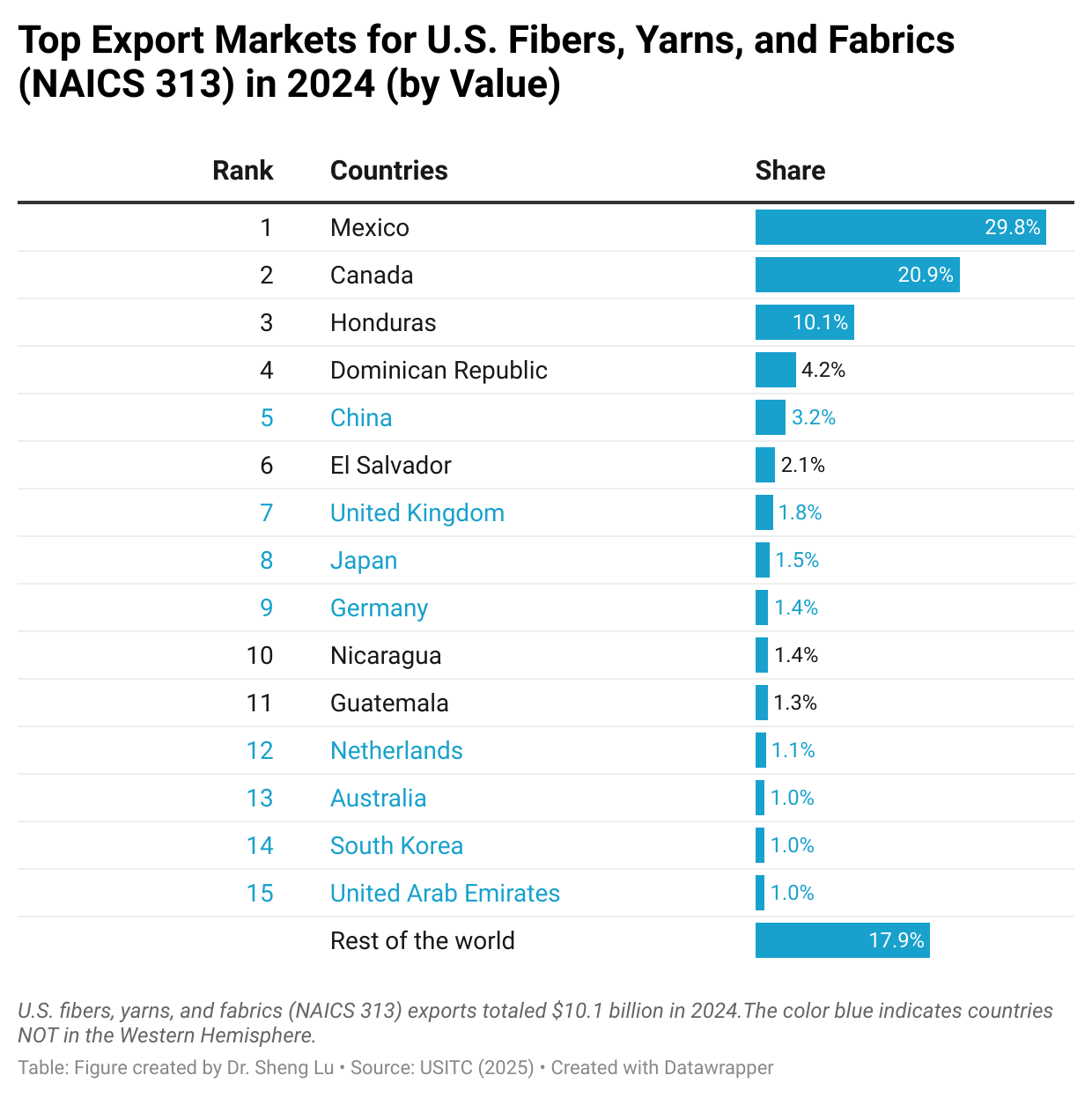

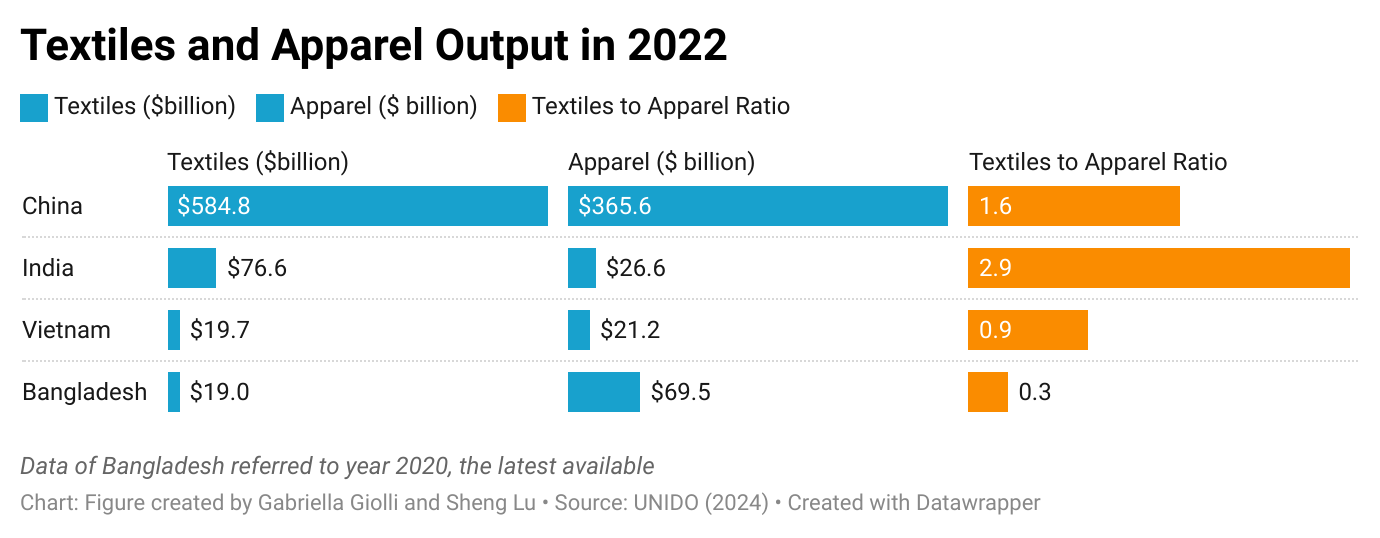

Third, the U.S. is no longer a dominant supplier of textile raw materials to the Western Hemisphere. Interestingly enough, when evaluating all major traders, including key Asian textile suppliers, namely China, South Korea, and Japan, the U.S. consistently ranked between 5th and 6th as a supplier (Hub score) and between 3rd and 6th as a receiver (Authority score) from 2010 to 2024. In contrast, Asian countries, particularly South Korea and Japan, not only achieved higher Hub scores but saw those scores gradually rise between 2015 and 2024. In other words, while the U.S. remains a major player, CAFTA-DR and USMCA members have increasingly diversified their textile import sources, including from Asian suppliers.

Additionally, the results show that the textile raw material trade network in the Western Hemisphere is highly resilient and self-reinforcing. This was demonstrated by the consistently higher PageRank scores of CAFTA-DR and USMCA members, such as Guatemala, El Salvador, Mexico, and the U.S., compared to Asian suppliers like Japan, South Korea, and China from 2010 to 2024. This pattern means that trade in textile raw materials among Western Hemisphere countries, including the U.S., operates like a closely connected “small town,” with strong, mutual internal links. Meanwhile, Asian suppliers, even though they are becoming more important sources of material, remain on the periphery as “outsiders” to this central regional network.

Overall, the results emphasize the success of a resilient regional textile raw material trade network in the Western Hemisphere, supported by regional trade agreements like the CAFTA-DR and USMCA. It can be explored further how to better balance deeper regional integration with strategic openness to improve access to textile raw materials for countries in the region.

By Sheng Lu