The original interview (in Spanish) is available HERE. Below is the translated version.

Question: Is there a reversal in the globalization of fashion?

Sheng Lu: The fashion industry is becoming more global AND regional — the making and selling of a garment “travel” through more and more countries. Just look at the label of a Gap sweatshirt: it is an American clothing brand, but the product is “Made in Vietnam,” and the label includes the size standards in six different countries. The business model of the fashion industry today is “making anywhere in the world and selling anywhere in the world.”

Q .: What do you mean the industry is becoming more “regional”?

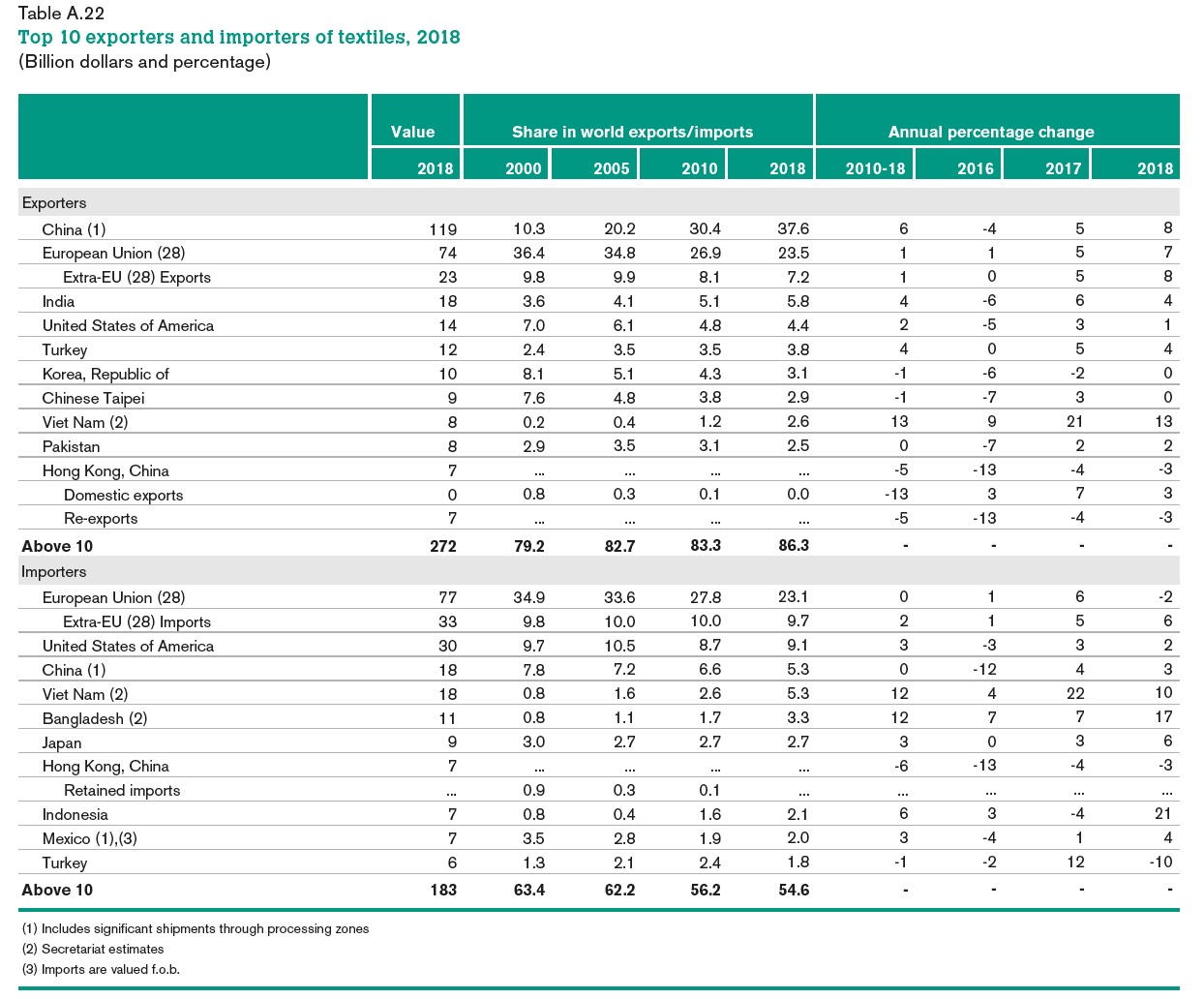

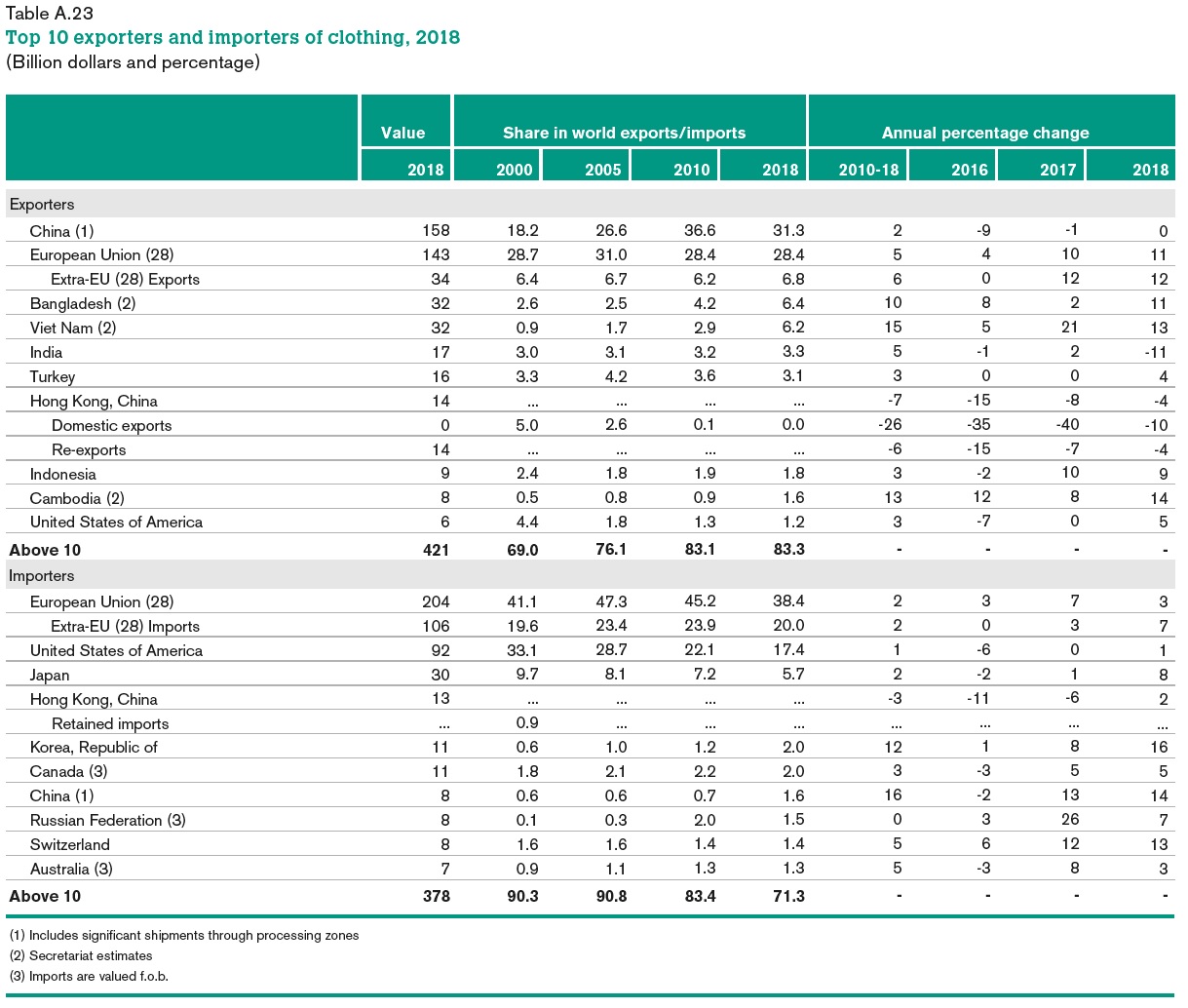

Sheng Lu: The trade flows of textiles and apparel today are heavily influenced by regional free trade agreements (FTAs). For example, while China is known as the world’s largest apparel producer and exporter, nearly 50% of the clothing consumed by European consumers are still produced by EU countries themselves. Notably, consumers have different expectations for clothing: many are price-sensitive, but others prefer more trendy items, which requires “near sourcing”—this explains why fashion companies have to adopt a more balanced sourcing portfolio.

Q .: Is the price still the most important factor in fashion companies’ sourcing decisions?

Sheng Lu: Sourcing is far more than just about chasing for the lowest cost. Sourcing decisions today have to consider a mix of factors, ranging from flexibility, speed to market, sustainability, to compliance risks. In fact, few companies “put all eggs in one basket.” My recent studies show that both in the United States and the EU, fashion companies with more than 1,000 employees, typically sourced from more than twenty different countries—sometimes even exceed forty. Behind such a diversified sourcing practice is the necessity to strike a balance between so many different sourcing factors.

Q .: Is apparel sourcing becoming more diversified today than a decade ago?

Sheng Lu: From my observations, fashion companies are souring from more countries and regions than a decade ago, but not in terms of producers. Especially in the last two or three years, I see some large companies are consolidating their supplier base to build a closer relationship with key vendors. The reason is the same as mentioned earlier: a very competitive price is not enough for apparel sourcing today.

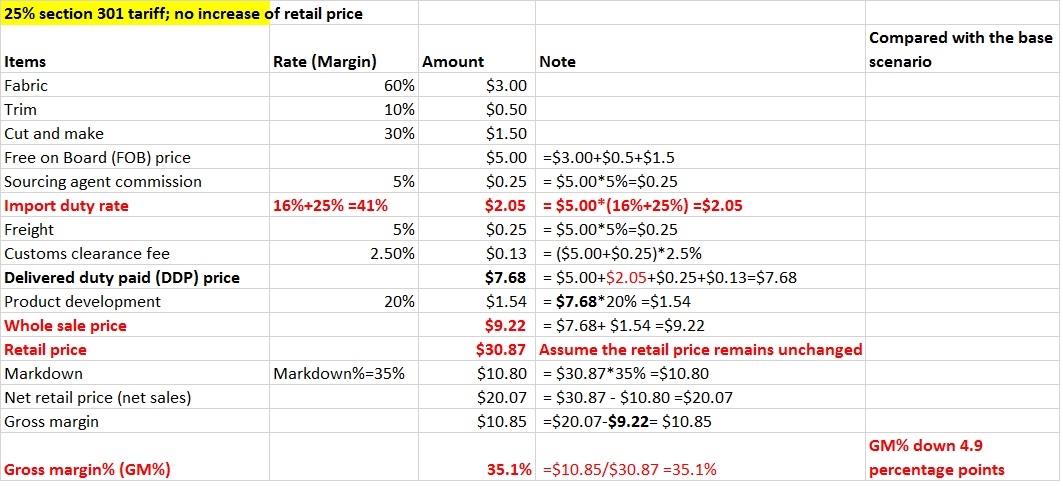

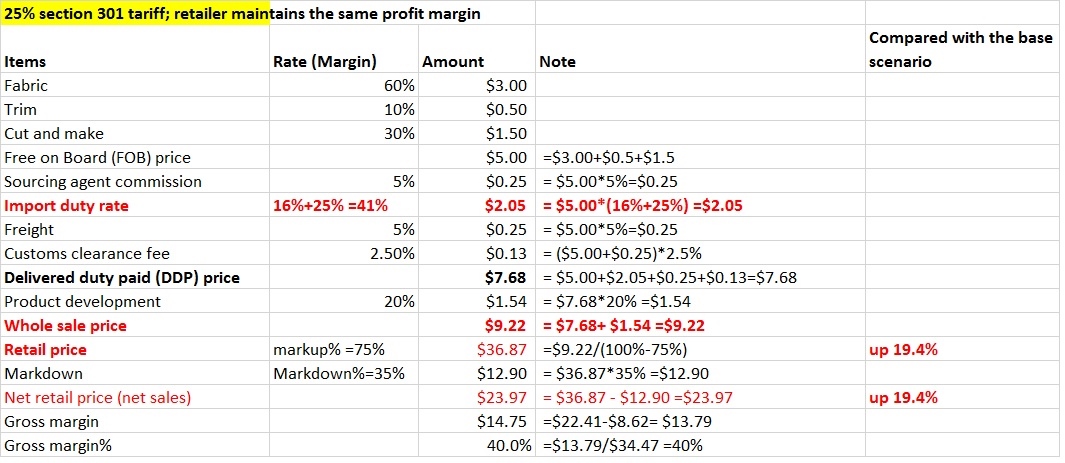

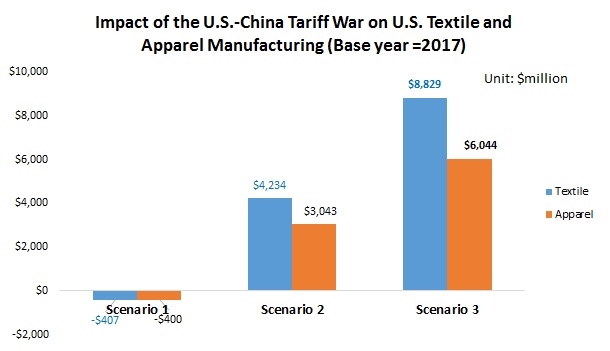

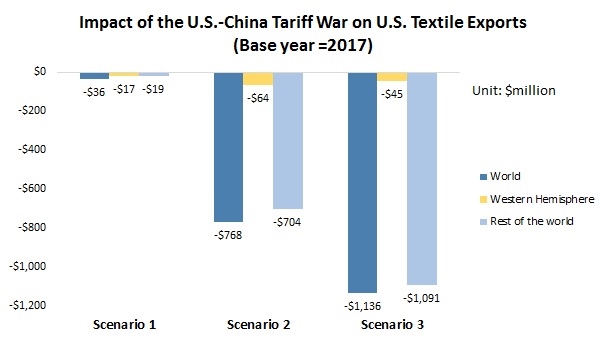

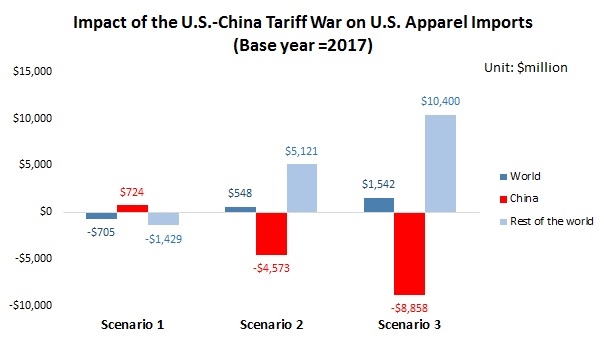

Q .: How has the tariff war between the United States and China affected apparel sourcing?

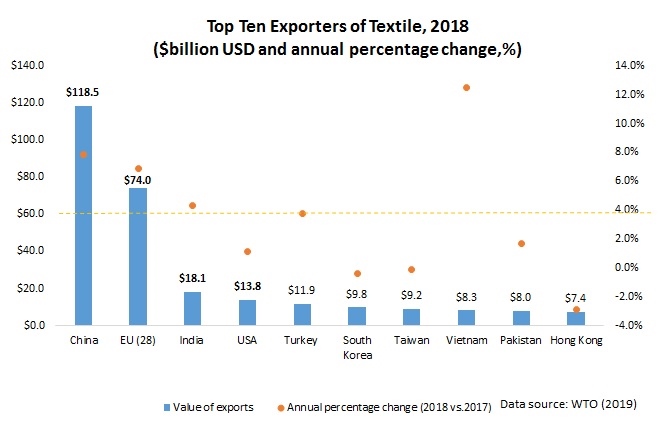

Sheng Lu: The trade war between the United States and China is having big impacts on apparel sourcing that go beyond the two countries. Notably, American fashion brands and retailers are moving sourcing orders from China to other Asian countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh. However, finding China’s alternatives is anything but easy. Despite the tariff war, China remains a competitive player in apparel sourcing. The unparalleled production capacity that can fulfill orders nearly for any products in any quantity, and the ability to comply with complex sustainability and social responsibility regulations are among China’s unique competitive advantages. Understandably, companies are not giving up sourcing from China, as there are few other “balanced” sourcing destinations in the world. That being said, it is important to recognize that the big landscape of apparel sourcing is evolving. Even in Europe, which is not having a trade war with China, apparel “Made in China” is seeing a notable decline in its market share.

Q .: How is China adapting?

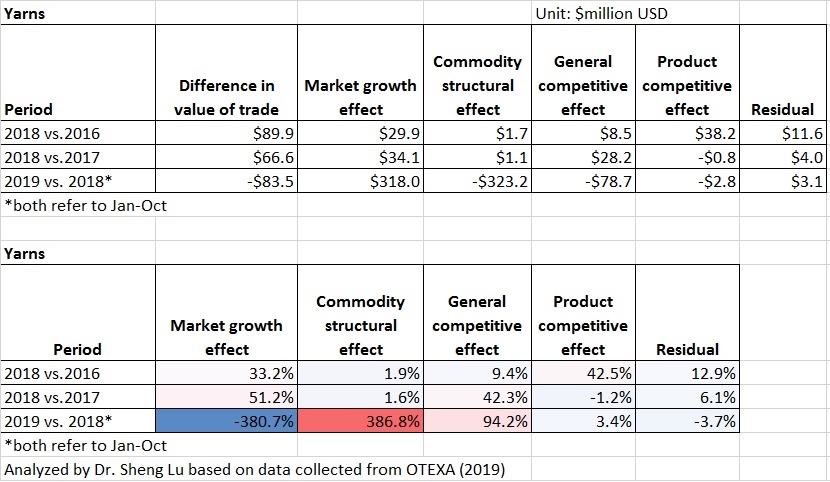

Sheng Lu: The textile and apparel industry in China is undergoing a structural change. Partially caused by the tariff war, apparel producers in China are increasingly moving their factories to nearby Asian countries (especially for big-volume and/or relatively low value-added product categories). Meanwhile, China itself is changing from an apparel producer to become a leading textile supplier for other apparel-exporting countries in Asia. This is NOT a temporary move, but a permanent transition, which has happened in many industrialized economies in history. Somehow, the tariff war has accelerated the adjustment process, however.

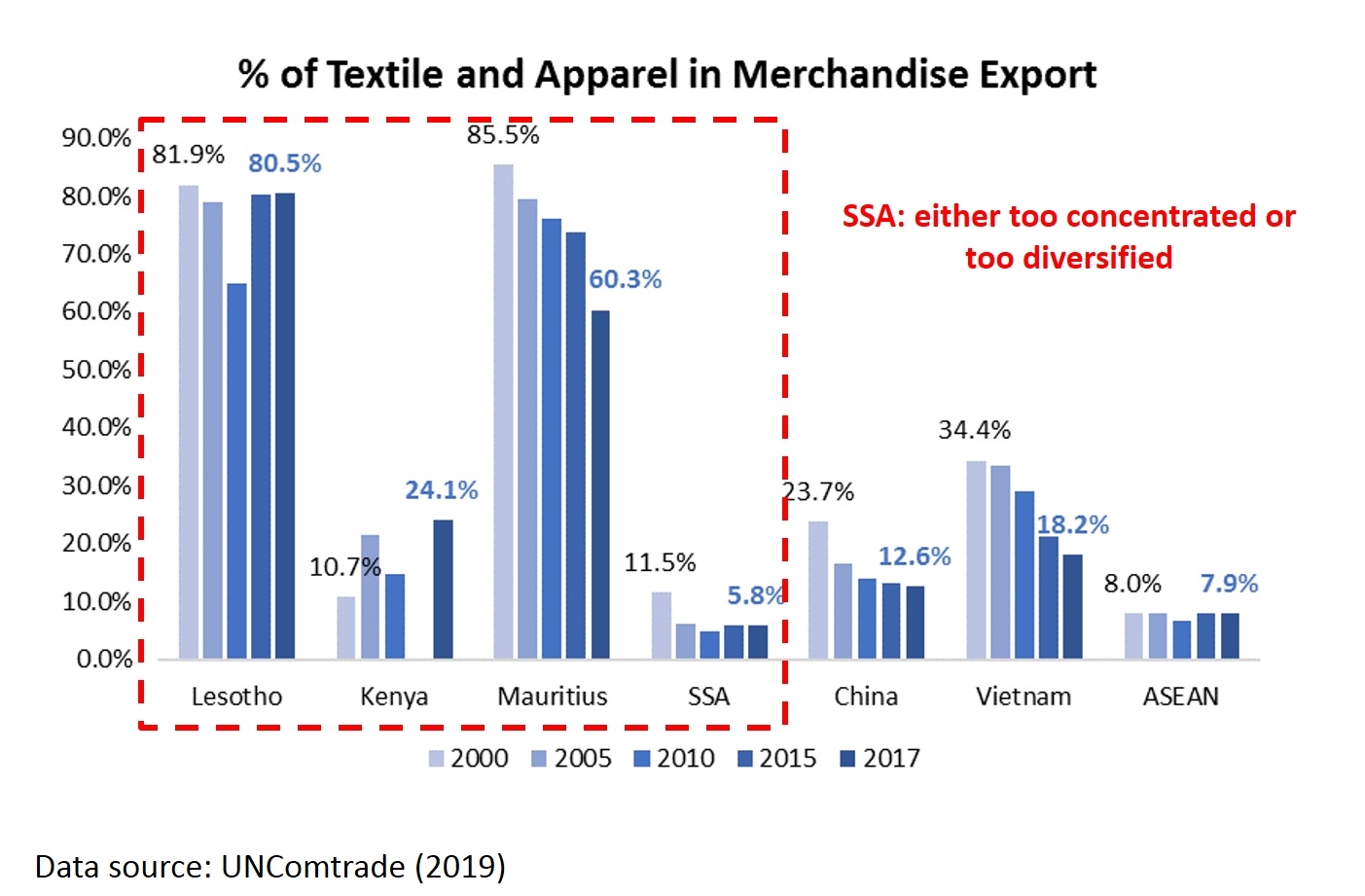

Q .: Will Africa be the next hub for apparel sourcing in the near future?

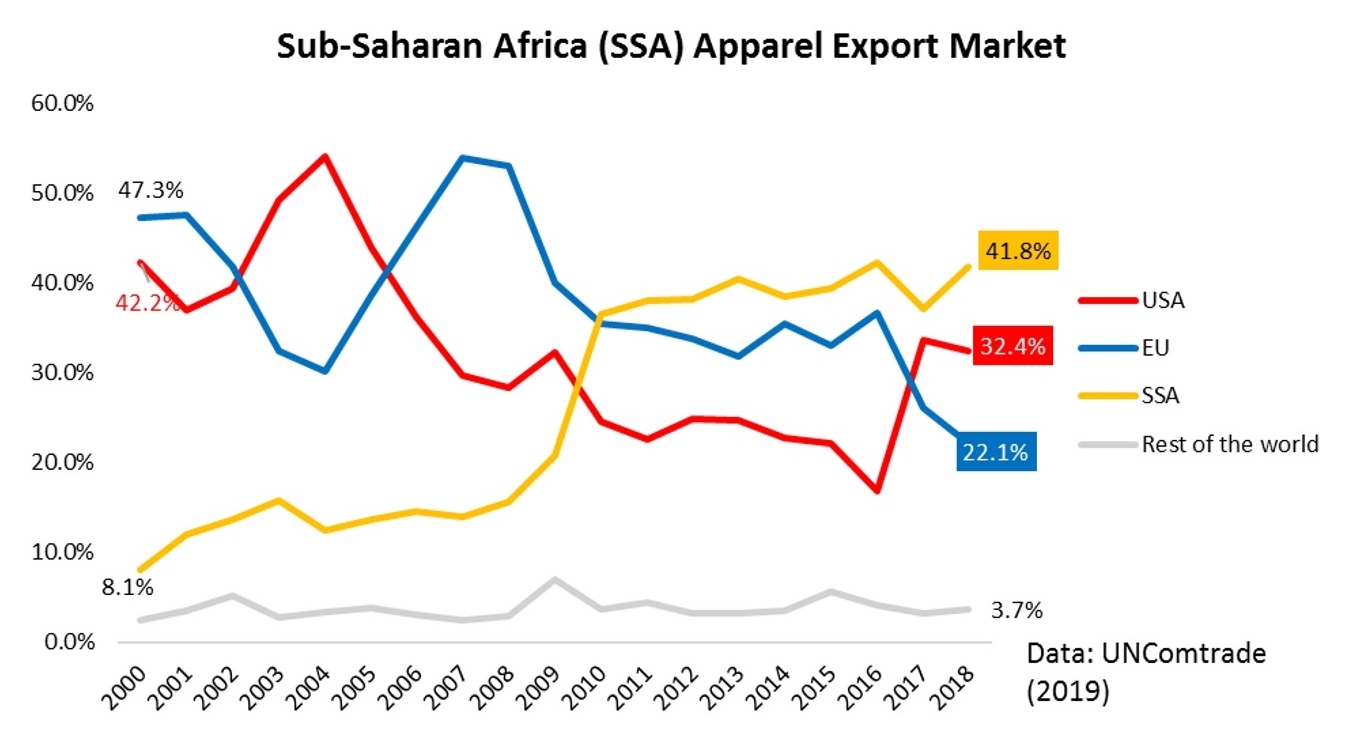

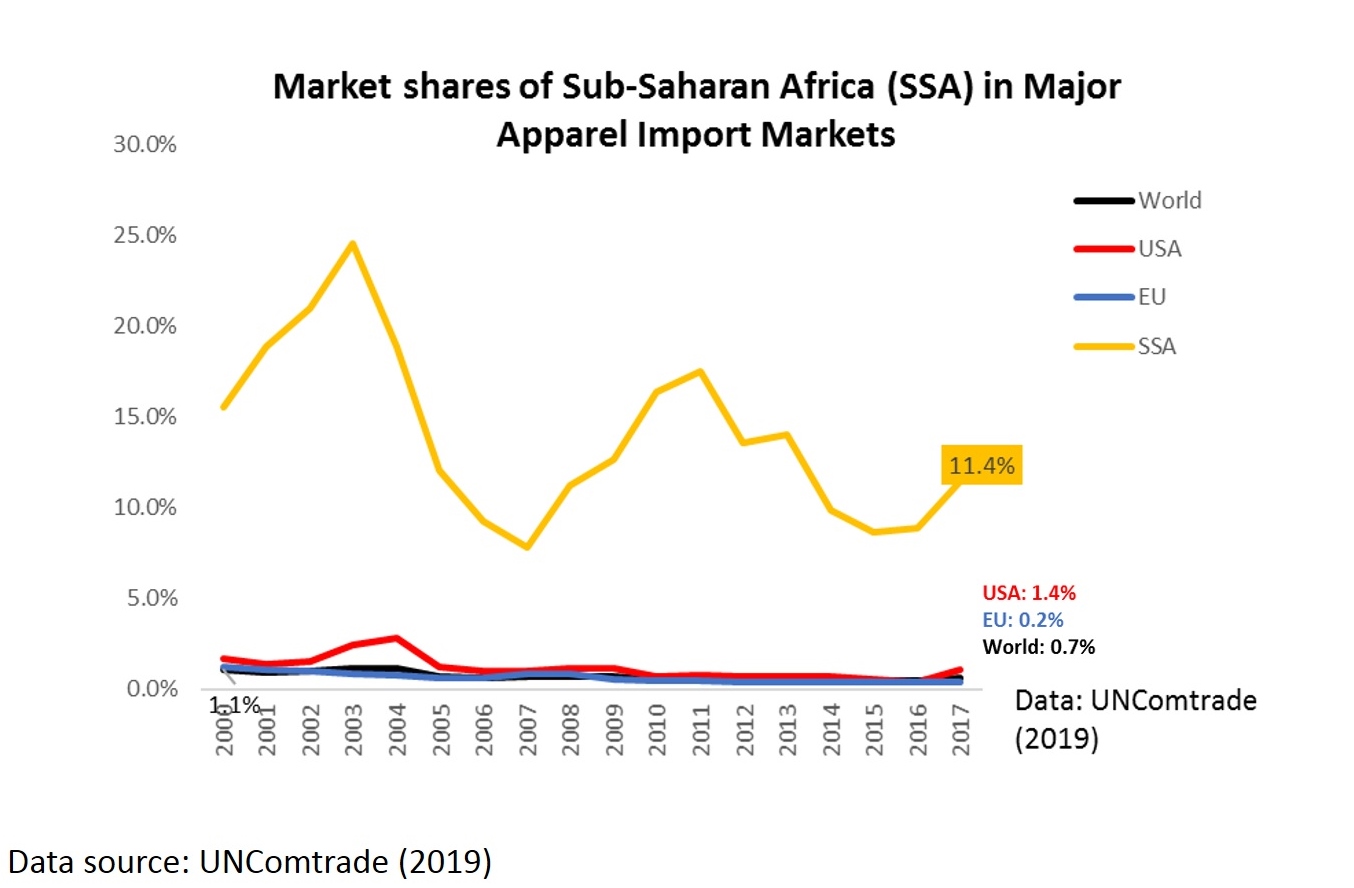

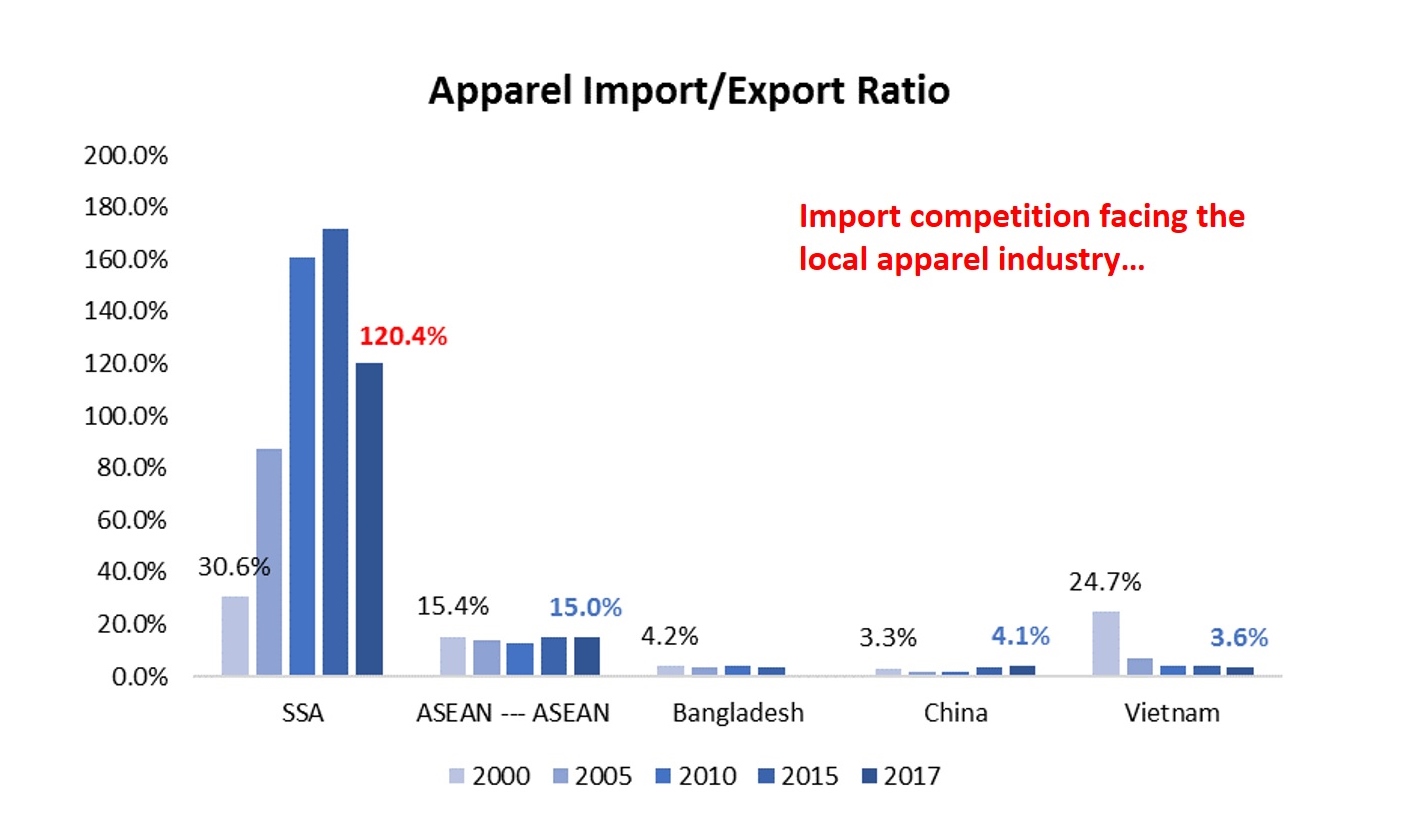

Sheng Lu: As textile and clothing trade is turning more regional-based, Africa is facing significant challenges to become an attractive tier-1 sourcing base for Western fashion brands and apparel retailers.

Q .: Why is that?

Sheng Lu: In general, there are three primary apparel import markets in the world: the United States, the European Union, and Japan—as of 2018, these three regions altogether still accounted for as many as 70% of the world apparel imports. Surely, Asian countries are important apparel suppliers for all these three regions. However, each of these three markets also has its respective regional suppliers—Mexico and Central & South American countries for the United States, China, and a few Southeast Asian countries for Japan and Eastern European countries for the EU market. Other than geographic proximity, often, these regional suppliers also enjoy preferential market access to the US, EU, and Japan provided by regional free trade agreements.

Africa, on the other hand, is not close to any of these three major apparel import markets geographically. Why would fashion companies in the United States, Japan, or the EU have to source from Africa when there are so many other options available?

Q .: For price?

Sheng Lu: Several trade preference programs currently offer apparel exporters in African countries preferential or duty-free market access to the United States, the EU, and Japan (such as the African Growth Opportunity Act and the EU and Japan Generalized System of Preferences programs). However, sourcing from Africa will entail other extra costs—for example, the raw material cost will be higher as yarns and fabrics have to be imported from Asia first, and the transportation bill could be costly due to the poor infrastructure. Further, not like their counterpart in Asia, the apparel industry is not regarded as a development priority in many African countries, which continue to rely heavily on the export of raw materials instead. Manufacturing for the local market is also complicated—apparel producers in Africa are struggling with both the cheap clothing imported from Asia and the mounting used clothing sent from the West.

Q .: It is said that fashion might be the most regulated sector in international trade other than agriculture. How to explain this?

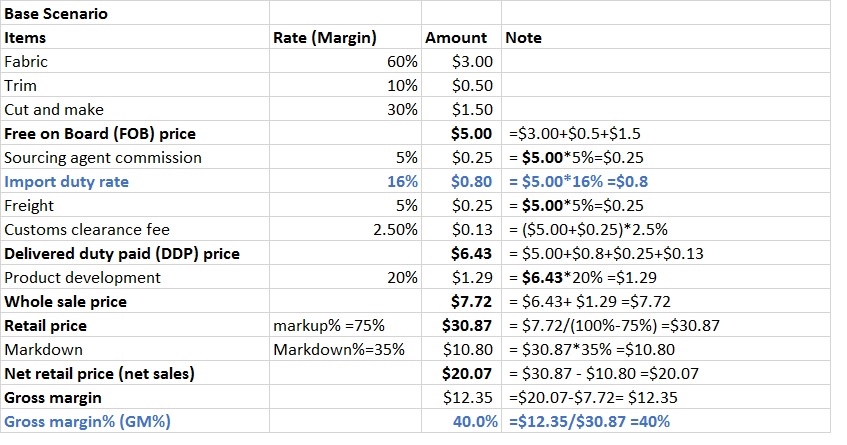

Sheng Lu: I think we need some changes here. For example, in 2018, textiles and apparel accounted for only 5% of the total U.S. merchandise imports but contributed nearly 40% of the tariff revenue collected. This phenomenon, which makes no sense economically, is the result of the industry lobby—trying to protect domestic manufacturers from import competition.

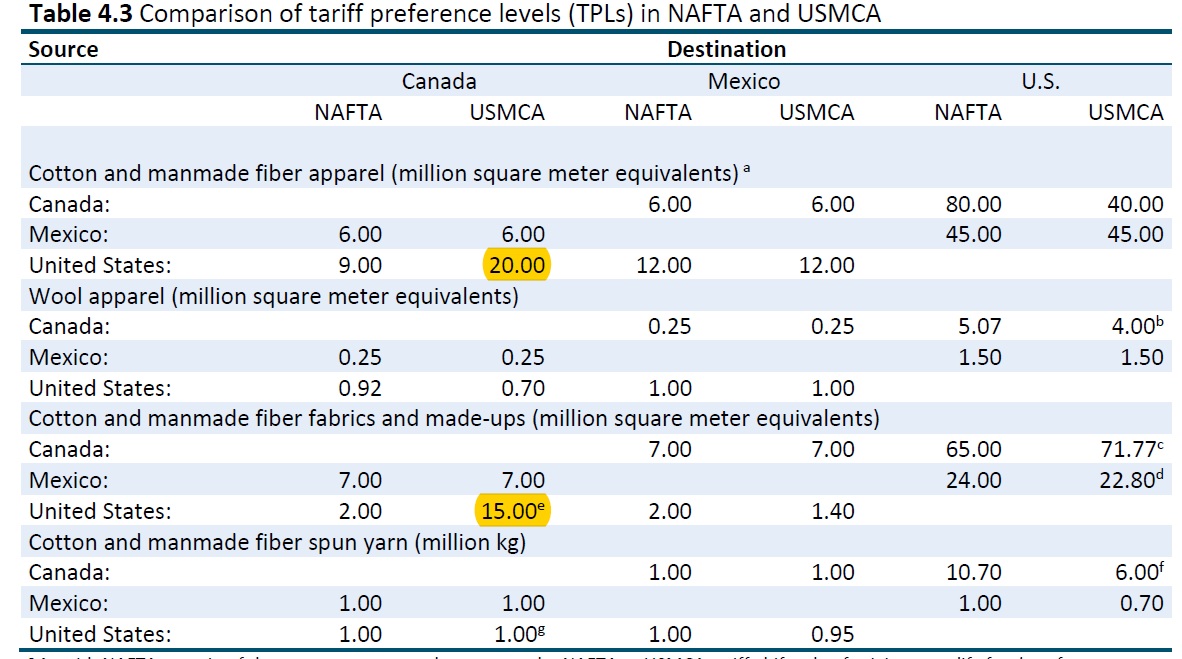

As another example, around 15%-17% of Mexico’s clothing exports to the United States do not claim the duty-free benefits provided by the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), as the NAFTA rules of origin strictly require the using of regional yarns and fabrics for qualified apparel items. In the end, companies prefer bigger savings on the raw material cost than claiming the NAFTA duty-saving benefits. We should think about how to modernize these trade rules and make them more supply-chain friendly in the 21st century.

Meanwhile, policymakers are developing new regulations to address some emerging areas in international trade, such as E-commerce, labor standards and environmental protection. Increasingly, trade policy is moving from “measures at the border” to “measures behind the borders.”