Category: FASH455 course material

ModCloth Sourcing and Supply Chain Strategies during the Pandemic

Speaker: Linda Ollmann, Director – Sourcing Operations, ModCloth

Event summary

ModCloth is a womenswear company that strives to empower women along every step of their manufacturing process. The customer loves the clothing and the pieces can be utilized in many different ways throughout many different seasons.

As of right now, ModCloth does most of their sourcing partnerships with vendors in China, largely because vendors in China were able to give ModCloth the most efficient price point at the shortest lead time. However, ModCloth did start to look for vendors outside of China in countries such as Vietnam, Sri Lanka, and India, but they found that the lead times were still the shortest when they sourced with vendors in China.

While ModCloth wants to continue having short lead times to satisfy their customer, they have some new sourcing strategies that they are going to be implementing in the near future. One thing they are going to do is find the best suppliers possible to get their fabric from so that their customers are happy and can even possibly love the company even more than they already do. In addition to this, ModCloth is dedicated to pursuing sustainable practices and this includes within the factories that they partner with. They also want to find a way to continue having a shorter lead time from the time customers order a garment to the time it gets delivered at their doorstep, all while having a low carbon footprint and being as environmentally conscious as possible.

Just like every other company in the world, ModCloth was impacted by COVID-19. However, since ModCloth started out as an entirely ecommerce brand they were able to adapt to the new virtual norm very well. They decided that with the pandemic slowing everything down, it was important that they focus on improving the company from the inside out. This helped them become more stable internally so they could inevitably build the brand up again on the outside. People have been primarily shopping online due to the closure of brick and mortar stores, so ModCloth did not see too much of a dip in their sales.

ModCloth is very interested in what their customers want and need. Their customers have expressed a need for more sustainable clothing and fabrics and this is exactly what ModCloth wants to give to them. It was mentioned in the webinar that it is easy to put information about the sustainability of a garment in the product description on their website which helps the customer really understand where the piece of clothing they are about to purchase is coming from. This will help customers remain faithful in the brand as well as help the customer feel connected to the brand

Summarized by Lexi Dembo (FASH455 spring 2021)

The Future of Asia as a Textile and Apparel Sourcing Base—Discussion Questions from Students in FASH455

#1: How to explain the phenomenon that US fashion companies are diversifying apparel sourcing from China, but not so much from the Asia region? For example, as of 2020, still, around 75% of US apparel imports came from Asian countries.

#2: From the readings and your observation, to which extent will automation challenge the conclusions of the “flying geese model” and the evolution pattern of Asian countries’ textile and apparel industry over the past decades?

#3: It could be a crazy idea, but given the current business environment, what would the textile and apparel supply chain in Asia look like without “Made in China”? What would be the implications for US fashion companies sourcing strategies?

#4: RCEP members are with a diverse competitiveness in textile and apparel production and exports. Several leading Asian apparel-exporting countries are not RCEP members (such as Bangladesh). Is it unavoidable that RCEP will create BOTH winners and losers for textile and apparel trade? How so?

#5: Is the growth model and development path of Asian countries’ textile and apparel industry an exception—meaning it is challenging to apply it to the rest of the world, such as the Western Hemisphere and Africa? What is your view?

#6: What is your outlook of Asia as a textile and apparel-sourcing base in the post-Covid world? Why?

(Welcome to our online discussion. For students in FASH455, please address at least two questions and mention the question number (#) in your reply)

How Is the Pandemic Changing the Global Fashion Industry?

Related readings

FASH455 Interview Series—QVC Global Sourcing Internship (Guest: Lora Merryman)

About Lora Merryman

Lora Merryman is a Master of Science student in Fashion and Apparel Studies at the University of Delaware (class of 2021). She also graduated from the UD with a Bachelor’s Science in Fashion Merchandising in 2020. She currently works for QVC as a global sourcing intern.

Lora was selected as a 2020 University of Delaware summer scholar. She also served as a graduate teaching assistant for FASH455 in Fall 2020 and Winter 2021. Lora is the author of a recent research publication on data science education for fashion majors, featured by Just-Style and several other industry news outlets.

US-China Tariff War During COVID-19—Discussion Questions from Students in FASH455

#1 Studies show that the Section 301 punitive tariff on imports from China hurts both US fashion retailers and ordinary consumers. But why doesn’t President Biden announce to remove the tariffs and stop the trade war?

#2 It doesn’t seem the tariff war with China has brought more apparel manufacturing back to the US. Is this result expected or surprising? How does the outcome of the trade war support or challenge the trade theories we learned in the class (e.g., mercantilism, absolute advantage, comparative advantage, and factor proportion theories)?

#3 The U.S.-China tariff war continues during the pandemic, resulting in higher sourcing costs for US fashion brands and retailers, which have been struggling hard financially. In such a case, if you were the CEO of a leading US fashion brand, why or why not would you pass the tariff burden to consumers, i.e., ask consumers to pay a higher price?

#4 Why or why not do you think the tariff war with China has fundamentally shifted US fashion companies’ sourcing strategy?

#5 What’s your take on “tariff engineering” adopted by fashion companies? A smart idea? Loophole? Controversial? Need to be encouraged/discouraged? And Why?

#6 Any reflections on the video discussion (above) regarding the US apparel industry’s view on the impact of the tariff war during the pandemic?

(Welcome to our online discussion. For students in FASH455, please address at least two questions and mention the question number (#) in your reply)

[Discussion is closed]

Globalization and Its Implications for the Fashion Industry—Discussion Questions from Students in FASH455

#1 Why or why not do you think VF Corporation should de-globalize its supply chain—for example, bringing more sourcing and production back to the United States?

#2 Given such a globalized operation, should we still call VF Corporation an American company? Also, does the label “Made in ___” still matter today?

#3 Is the sole benefit of globalization helping us get cheaper products? How to convince US garment workers who lost their jobs because of increased import competition that they benefit from globalization also?

#4 How has COVID-19 changed your understanding of the benefits, costs, and debates on globalization? Do we still need globalization in a post-COVID world? Why?

#5 Throughout history, globalization has been viewed as a two-sided debate with social groups weighing its benefits and negative costs. With the emergence of COVID-19, how do you think certain social groups’ opinions towards globalization will change?

(Welcome to our online discussion. For students in FASH455, please address at least two questions and mention the question number (#) in your reply)

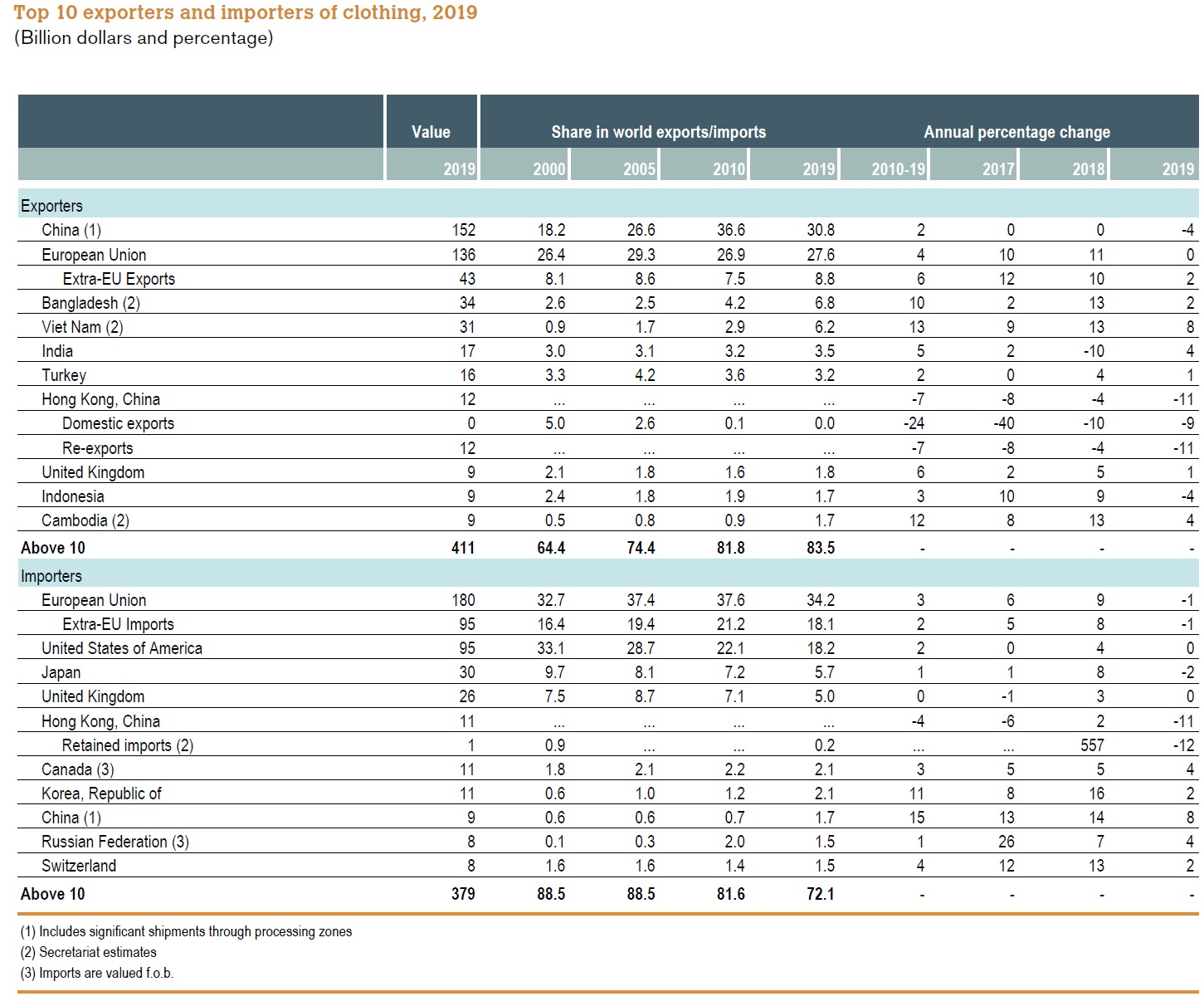

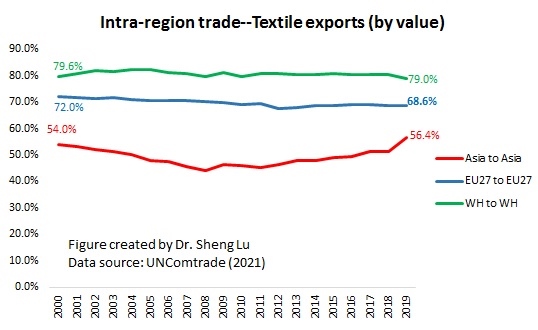

Which Apparel Sourcing Factors Matter?

Key findings:

The apparel sourcing formula is getting ever more sophisticated today. US fashion brands and retailers consider a wide range of factors when deciding where to source their products. The long list of sourcing factors includes #1 Capacity, #2 Price & tariff, #3 Stability, #4 Sustainability, and #5 Quality (see the table below).

When evaluating the world’s top 27 largest apparel supplying countries’ performance, no souring destination appears to be perfect. In general, fashion brands and retailers have many choices for sourcing destinations that can meet their demand for production capacity, price point, and quality. However, fashion companies face much more limited options when seeking an apparel sourcing destination with a stable financial and political environment and a strong sustainability record.

When we compare the trade volume and the performance against the five primary sourcing factors:

- Apparel sourcing today is no longer a “winner takes all” game. Notably, the factor “Capacity” is suggested to have limited impacts on the value of apparel imports from a particular sourcing destination.

- Apparel sourcing is not merely about “competing on price” either--the impact of the factor “Price & tariff” on the pattern of apparel imports statistically is not significant.

- Improving financial and political stability as well as product quality can help a country enhance its attractiveness as an apparel sourcing base. In particular, American and Asia-based fashion companies seem to give substantial weight to the factors of “Stability” and “Product quality” in their sourcing decisions.

- Fashion companies’ current sourcing model does not always provide strong financial rewards for sustainability. Interestingly, the result indicates that a higher score for the factor “sustainability” does NOT result in more sourcing orders at the country level. Behind the result, fashion companies today likely consider sustainability and compliance at the vendor level rather than at the country level in their sourcing decisions. It is also likely that sustainability and compliance are treated more as pre-requisite or “bottom-line” criteria instead of a factor to determine the volume of the sourcing orders.

In conclusion, fashion companies’ sourcing decisions seem to be more complicated and subtle than what is often described in public.

By Emma Davis and Sheng Lu

Further reading: Emma Davis & Sheng Lu (2021). Which apparel sourcing factors matter the most?. Just-Style.

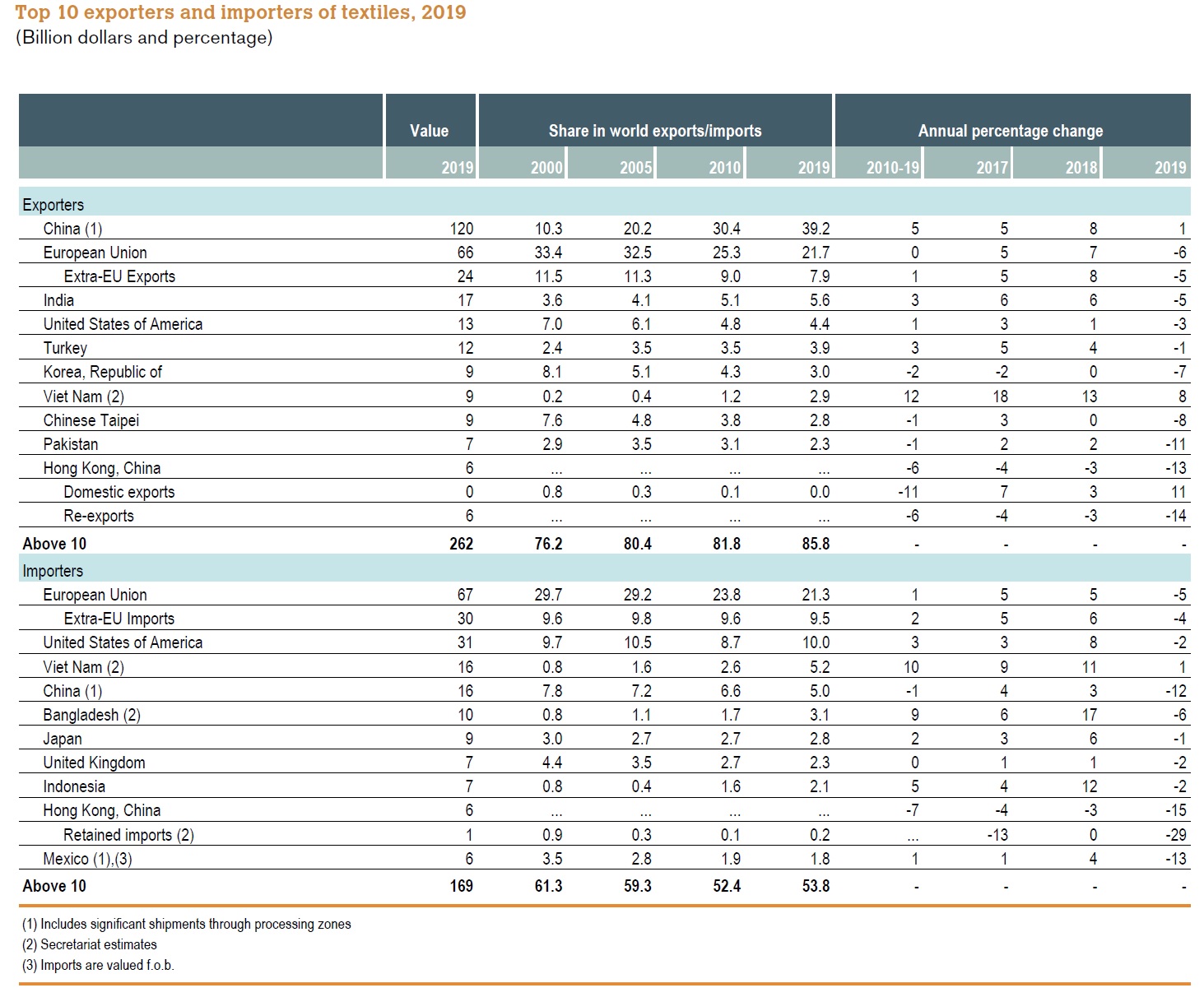

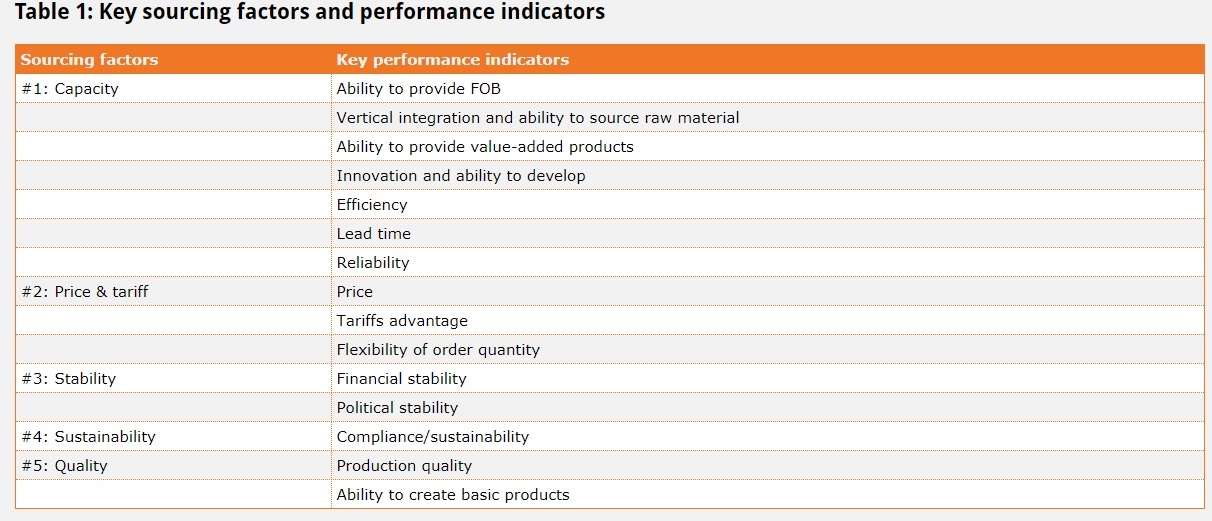

Regional Supply Chain Remains a Key Feature of World Textile and Apparel Trade

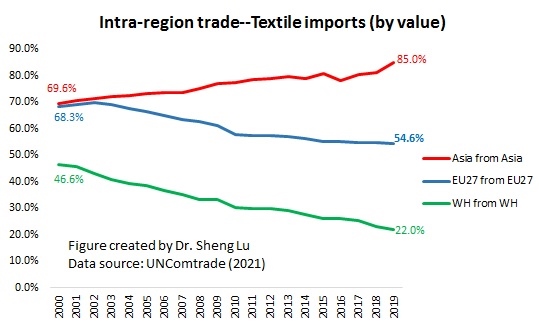

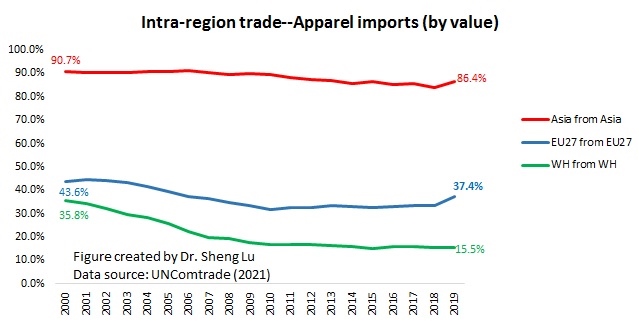

While textile and apparel is well-known as a global sector, the latest statistics show that world textile and apparel trade patterns remain largely regional-based. Three particular regional textile and apparel trade flows are critical to watch:

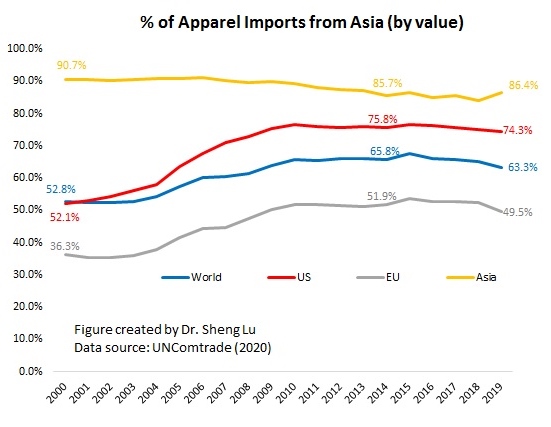

First, Asian countries are increasingly sourcing textile raw material from within the region. As much as 85% of Asian countries’ textile imports came from other Asian countries in 2019, a substantial increase from only 70% in the 2000s. This result reflects the formation of an ever more integrated regional textile and apparel supply chain in Asia. However, as Asian countries become more economically integrated, textile and apparel producers in other parts of the world could find it more challenging to get involved in the region. With the recent reaching of several mega free trade agreements among countries in the Asia-Pacific region, such as the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the pattern of “Made in Asia for Asia” is likely to strengthen further.

Second, the EU intra-region trade pattern for textile and apparel stays relatively strong and stable. Intra-region trade refers to trade flows between EU members. Statistics show that 54.6% of EU(27) members’ textile imports and 37.4% of their apparel imports came from within the EU(27) region in 2019. This pattern only slightly changed over the past decade. In other words, despite the reported increasing competition from Asian suppliers, many of which even enjoy duty-free market access to the EU market (such as through the EU Everything But Arms program), a substantial share of apparel sold in the EU markets are still locally made.

EU consumers’ preferences for “slow fashion” (i.e., purchasing less but for more durable products with higher quality) may contribute to the stable EU intra-region trade pattern. Many EU consumers also see textile and apparel as cultural products and do NOT shop simply for the price. This explains why Western EU countries such as Italy, Germany, and France rank the top apparel producers and exporters in the EU region despite their high wage and production costs.

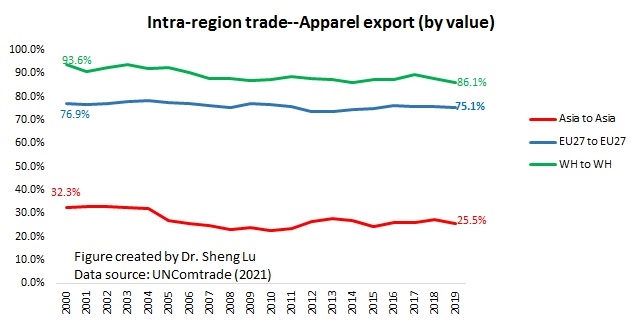

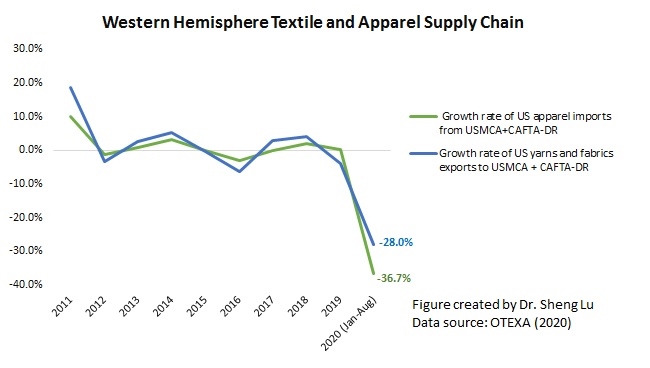

Third, the Western Hemisphere (WH) supply chain faces significant challenges despite the seemingly growing popularity of “near-sourcing.” On the one hand, textile and apparel exporters in the Western-Hemisphere still rely heavily on the regional market. In 2019, respectively, as much as 79% of textiles and 86% of apparel exports from countries in the Western Hemisphere went to the same region.

However, on the other hand, the Western-Hemisphere supply chain is facing increasing competition from Asian suppliers. For example, in 2019, only 22% of North, South, and Central American countries’ textile imports and 15% of their apparel imports came from within the Western Hemisphere, a new record low in ten years. Similarly, in the first eleven months of 2020, only 15.7% of US apparel imports came from the Western Hemisphere, down from 17.1% in 2019 before the pandemic. The limited local textile production capacity and the high production cost are the two notable factors that discourage US fashion brands and retailers from committing to more “near-sourcing” from the Western Hemisphere.

In comparison, Asian countries supplied a new record high of 62.2% of textiles and 75% apparel to countries in the Western Hemisphere in 2019, up from 49.1% and 71.1% ten years ago. This trend suggests that as the competitiveness of “Factory Asia” continues to improve, even regional trade agreements (such as USMCA and CAFTA-DR) and their restrictive “yarn-forward” rules of origin have limits to protect the Western Hemisphere supply chain.

In comparison, Asian countries supplied a new record high of 62.2% of textiles and 75% apparel to countries in the Western Hemisphere in 2019, up from 49.1% and 71.1% ten years ago. This trend suggests that as the competitiveness of “Factory Asia” continues to improve, even regional trade agreements (such as USMCA and CAFTA-DR) and their restrictive “yarn-forward” rules of origin have limits to protect the Western Hemisphere supply chain.

Additionally, many say that the reaching of RCEP creates new pressure for the new Biden administration to consider joining the CPTPP and strengthening economic ties with countries in the Asia-Pacific region. Notably, several USMCA and CAFTA-DR members, such as Mexico, also have RCEP or CPTPP membership. Apparel producers in these Western Hemisphere countries may find it more rewarding to access the cheaper textile raw material from Asia through CPTPP or RCEP rather than claiming the duty-saving benefits for finished garments under USMCA or CAFTA-DR. Like it or not, the Biden administration’s inaction will also have consequences.

by Sheng Lu

Further reading: Lu, Sheng. (2021). Regional supply chains still shape textile and apparel trade. Just-Style

US Apparel Sourcing Trends to Watch in 2021

Key points:

- Key themes in 2021: COVID-19+ trade policy

- U.S. apparel imports continue to rebound, but uncertainty remains

- Asia will remain the dominant apparel sourcing base

- U.S. fashion companies are NOT giving up China as one of their essential apparel-sourcing bases, although companies continue to reduce their “China exposure” overall. Meanwhile, do NOT underestimate the impact of non-economic factors on sourcing.

- No clear evidence suggests near sourcing from the Western Hemisphere is happening in a large scale

- Watch Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) and Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP). These two mega-free trade agreements could shape new textile and apparel supply chains in the Asia-Pacific region.

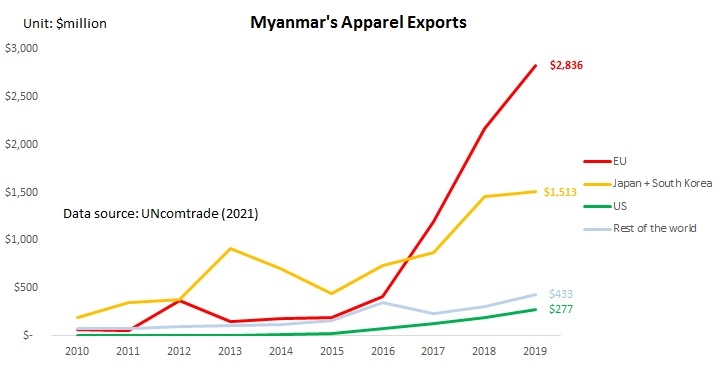

A Snapshot of Myanmar’s Apparel Industry and Export

See updated data: What’s Happening with Myanmar’s Apparel Exports (Updated August 2022)

First, the textile and apparel industry plays a significant role in Myanmar’s economy, particularly the export sector. Data from the UNComtrade shows that textile and apparel accounted for nearly 30% of Myanmar’s total merchandise exports in 2019, followed by footwear and luggage. Industry data also indicates that the textile, apparel, and footwear industry employed more than 1.1 million workers in Myanmar in 2018, up from only 0.3 million in 2016.

On the other hand, as a developing country, Myanmar highly depends on the imported textile raw material. As of 2019, nearly 83% of Myanmar’s textile imports came from China.

Second, since the United States lifted the import ban on Myanmar and the EU reinstated the Everything But Arms (EBA) trade preferences for the country in 2013, Myanmar has been one of the most popular emerging apparel sourcing bases among fashion companies. From 2015 to 2019, Myanmar’s apparel exports to the world enjoyed an impressive 57% annual growth. Myanmar’s apparel exports to the EU (97% annual growth) and the United States (78% annual growth) have been growing particularly fast.

From 2019 to 2020, some of the top fashion brands that carry apparel items “Made in Myanmar” include United Colors of Benetton, Next, Only, Guess, Jack & Jones, and Mango.

Second, the reasons why fashion companies source apparel from Myanmar are multiple:

- Thanks to foreign investment (e.g., nearly half of Myanmar’s garment factories are foreign-owned), Myanmar specializes in making relatively higher-quality functional/technical clothing (i.e., outwear like jackets and coats). This is different from many other apparel exporting countries like Bangladesh, Vietnam, and Cambodia, mostly exporting low-cost tops and bottoms.

- Myanmar’s apparel exports were able to enjoy duty-free market access in the EU, Japan, and South Korea. Myanmar was also a beneficiary of the US Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) program. This explains why Myanmar’s apparel exports mostly go to the EU (56%), Japan and South Korea (30%), and the US (5.5%).

- Relatively low production cost—garment workers earn around $85/month in 2019.

However, Myanmar still accounts for a tiny share in fashion companies’ total sourcing portfolio because of the size effect. For example, as of 2019, less than 0.1% of US and EU countries’ apparel imports came from Myanmar.

Third, western fashion brands could reevaluate their sourcing strategy from Myanmar because of its recent coup. Notably, in a new study, we find that apparel sourcing is not merely about “competing on price.” Instead, fashion companies give substantial weight to the factors of “political stability” and “financial stability” in their sourcing decisions—reputation risk matters. The country’s latest political instability will hurt Myanmar’s attractiveness as an apparel sourcing base, given many other alternatives out there.

Further, the international community, including the US and the EU, is considering new sanctions against Myanmar. Should Myanmar lose its EU’s EBA eligibility or no longer enjoy duty-free access to its key apparel export markets, the country’s apparel exports could be among the biggest losers. Notably, it could be challenging for Myanmar to find an alternative apparel export market during the pandemic. (for example, only 1.3% of Myanmar’s apparel exports went to China in 2019).

By Sheng Lu

Further reading:

- Myanmar’s Garment Factories Suffer One-Two Punch of Covid and Coup (Wall Street Journal)

- Myanmar coup clouds future of country’s crucial garment industry (Nikkei Asia Review)

Bangladesh Garments Manufacturer and Exporter Association (BGMEA) 2020 Sustainability Report

The full report is available HERE

Key findings:

The ready-made garment industry (RMG) is critical to Bangladesh economically. In 2018, RMG accounted for 84% of the country’s total exports and 11% of Bangladesh’s gross domestic product (GDP). The RMG industry supports about 4.1 million workers (including 65% female) in Bangladesh directly and additional 40 million workers through backward and forward linkage industries. North America and Europe are the two major destinations of RMG exports from Bangladesh.

Led by BGMEA, the Bangladeshi RMG industry has made efforts to improve in its social responsibility and environmental sustainability practices.

- Specific initiatives include regularly monitoring workplace safety & compliance, providing social standards training for factories, offering guidance for sustainable use of natural resources and green buildings, and improving workers’ various benefits (such as fair wage, skill development, gender equality and better working condition).

- The gender wage gap in Bangladesh was 2.2%, much lower than the 21.2% of the world average.

- The Bangladeshi RMG industry has also made efforts to promote freedom of association and collective bargaining, an important aspect of human rights for workers defined by the International Labor Organization (ILO). The number of trade unions in the RMG industry has increased from 138 in 2012 to around 800 in 2020.

The Bangladeshi RMG industry still faces several major challenges that need to be addressed. For example:

- A lack of skilled labor force and skill development opportunities. In some cases, the RMG factory owners have to pay more costs than they assume due to the fact that unskilled workers need more working hours than skilled workers.

- Pressure from competition and production cost. While RMG factories have to spend more on remediation and compliance investment, they are facing a declining selling price of their products. As a result, factories are struggling to maintain their social and environmental compliance while sustaining the business.

- Looking into the future, international buyers sourcing apparel from Bangladesh care most about the country’s safe working conditions, fair wages to the workers, no use of forced or child labor, social and environmental sustainability, and good business environment. In comparison, workers in the Bangladeshi garment industry care most about fair wages, bonuses on due time, a safe working environment, overtime, and job security.

Summarzied by Hailey Levin

Outlook 2021– Key Issues to Shape Apparel Sourcing

In January 2021, Just-Style consulted a panel of industry leaders and scholars in its Outlook 2021–Key Issues to Shape Apparel Sourcing Management Briefing. Below is my contribution to the report. All comments and suggestions are more than welcome!

What do you see as the biggest challenges – and opportunities – facing the apparel industry in 2021?

I see COVID-19 and market uncertainties caused by the contentious US-China relations as the two most significant challenges facing the apparel industry in 2021.

The difficulties imposed by COVID-19 on fashion businesses are twofold. First, with the resurgence of COVID cases worldwide, when and how quickly apparel consumption can rebound to the pre-COVID level remain hard to tell, particularly in leading consumption markets, including the United States and Europe. As the apparel business is buyer-driven, the industry’s full recovery is impossible without a strong return of consumers’ demand. Numerous studies also show that switching to making and selling PPE won’t be sufficient to make up for losses from regular businesses for most fashion companies.

Second, COVID-19 will also continue to post tremendous pressures on the supply side. In the 2020 Fashion Industry Benchmarking Study, which I conducted in collaboration with the US Fashion Industry Association (USFIA), the surveyed sourcing executives reported severe supply chain disruption during the pandemic. These disruptions come from multiple aspects, ranging from a labor shortage, a lack of textile raw materials, and a substantial cost increase in shipping and logistics. Even more concerning, many small and medium-sized (SME) vendors, particularly in the developing countries, are near the tipping point of bankruptcy after months of struggle with the order cancellation, mandatory lockdown measures, and a lack of financial support. The post-covid recovery of the apparel business relies on a capable, stable, and efficient textile and apparel supply chain, in which these SME vendors play a critical role.

In 2021, fashion companies also have to continue to deal with the ramifications of contentious US-China relations. On the one hand, the chance is slim that the punitive tariffs imposed on Chinese products, which affect most textiles and apparel, will soon go away. On the other hand, we cannot rule out the possibility that the US-China commercial relationship will deteriorate further in 2021, as more sensitive, complicated, and structural issues began to get involved, such as national security, forced labor, and human rights. Compared with President Trump’s unilateral trade actions, the new Biden administration may adopt a multilateral approach to pressure China. However, it also means more countries could be “dragged into” the US-China trade tensions, making it even more challenging for fashion companies to mitigate the trade war’s supply chain impacts.

Meanwhile, I see digitalization as a big opportunity for the apparel industry, not only in 2021 but also in the years to come. Fashion brands and retailers will increasingly find digitalization ubiquitous to their businesses—like air and electricity. In 2021, I expect fashion companies will make more efforts to creatively use digital technologies to interact with consumers, make transactions, develop products, and improve consumers’ online shopping experiences. Thanks to the adoption of digital tools, apparel companies may also find new opportunities to improve sustainability, better understand their customers through leveraging data science, and develop a more agile and nimble supply chain.

What’s happening with supply chains? How is the sourcing landscape likely to shift in 2021, and what can apparel firms and their suppliers do to stay ahead, remain competitive and build resilience for the future?

Apparel companies’ sourcing and supply chain strategies will continue to evolve in response to consumers’ shifting demand, COVID-19, and the new policy environment. Several trends are worth watching in 2021:

First, fashion companies’ sourcing bases at the country level will stay relatively stable in 2021 overall. For example, although it sounds a little contradictory, fashion companies will continue to treat China as an essential sourcing base and reduce their “China exposure” further, a process that has started years before the tariff war. Most apparel sourcing orders left China will go to China’s competitors in Asia, such as Vietnam, Bangladesh, and Cambodia. This also means that Asia, as a whole, will remain the single largest source of apparel imports, particularly for US and Asia-based fashion companies. In comparison, still, “near-sourcing” is NOT likely to happen on a large scale, mainly because “near-sourcing” requires enormous new investments to rebuild the supply chain, and most fashion companies do not have the resources to do so during the pandemic.

Second, sourcing diversification is slowing down at the firm level, and more apparel companies are switching to consolidate their existing sourcing base. For example, as the 2020 USFIA benchmarking study found, close to half of the respondents say they plan to “source from the same number of countries, but work with fewer vendors” through 2022. Another 20 percent of respondents say they would “source from fewer countries and work with fewer vendors.” The results are understandable– competition in the apparel industry is becoming supply chain-based. Building a strategic partnership with high-quality vendors will play an ever more critical role in supporting fashion brands and retailers’ efforts to achieve speed to market, flexibility and agility, sourcing cost control, and low compliance risk. Thus, apparel companies find it more urgent and rewarding to consolidate the existing sourcing base and resources and strengthen their key vendors’ relations.

Third, apparel sourcing executives still need to keep a close watch on trade policy in 2021. However, we may see fewer news headlines about trade and more “behind the door” advocacy and diplomacy. Specifically:

- US Section 301 actions: While the punitive tariffs on Chinese goods may not go away anytime soon, there could be a fight over whether the new Biden administration should continue granting certain companies exclusions from those tariffs. Further, in October 2020, the Trump Administration launched two new Section 301 investigations on Vietnam regarding its import and use of timber and reported “undervaluation currency.” The case is pending, but the stakes are high for fashion companies —Vietnam is often treated as the best alternative to sourcing from China and already accounting for nearly 20% of total US apparel imports.

- The US-China relationship: We all know the relationship is at its low-point, but the fact is many US fashion companies still treat China as one of their most promising markets to explore. China continues to expand its role in the Asia-based textile and apparel supply chain also. In a nutshell, more than ever, apparel executives need to care about what is going on in geopolitics. Hopefully, “tough times can breed positive outcomes.”

- CPTPP and RCEP: With the reaching of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) in November 2020, there are growing calls for the new Biden administration to consider rejoining the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) in some format to showcase the US presence in the Asia-Pacific region. To make the situation even more complicated, China has openly expressed its interest in joining the Comprehensive Progressive Agreement of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), commonly known as “the TPP without the US.” 2021 will be a critical time window for all stakeholders, including the apparel sector, to debate various trade policy options that could shape the future trade architecture in the Asia-Pacific region.

- Brexit: Brexit will enter a new phase in 2021 as the transition period ends on 31 December 2020. On the positive side, we have a playbook to follow—the UK has announced its new tariff schedules for various scenarios, which provide critical market predictability. We might also see the reaching of a new US-UK free trade agreement in the first half of the year, which will be exciting news for the apparel sector, particularly those in the luxury segment. However, as the US Trade Promotion Authority (TPA) is set to expire in July 2021, when and how soon such an agreement will enter into force will be another story. By no means trade policy in 2021 will go boring.

by Sheng Lu

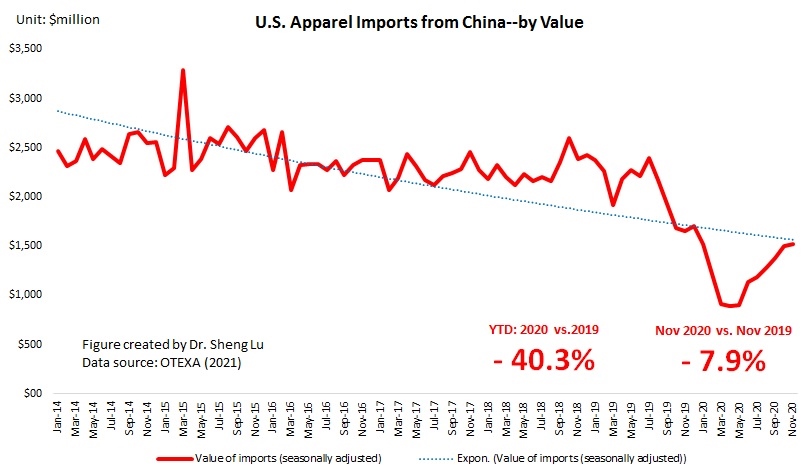

COVID-19 and U.S. Apparel Imports: Key Trends (Updated: January 2021)

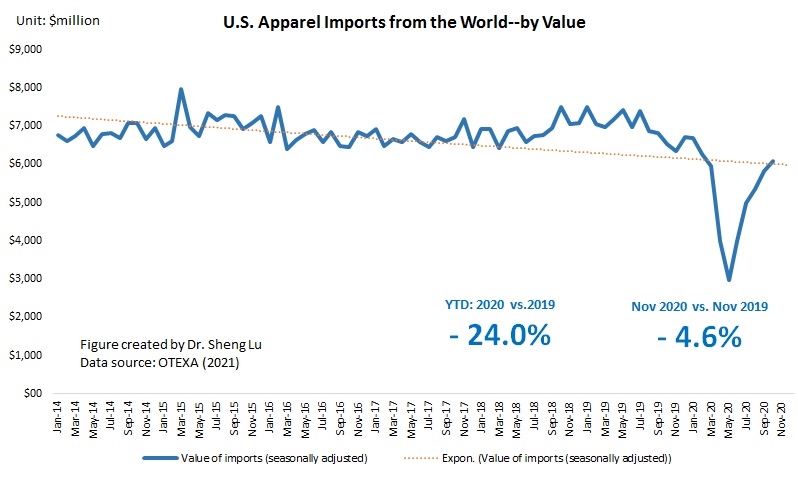

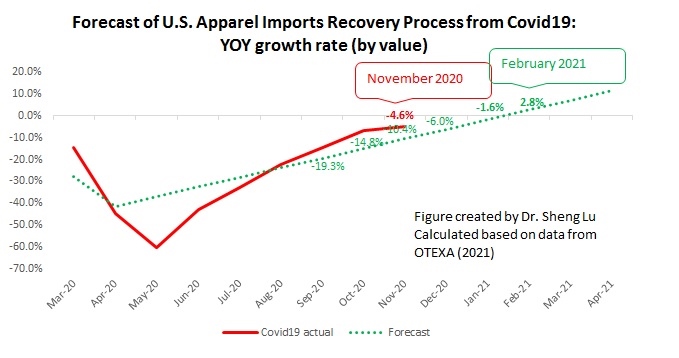

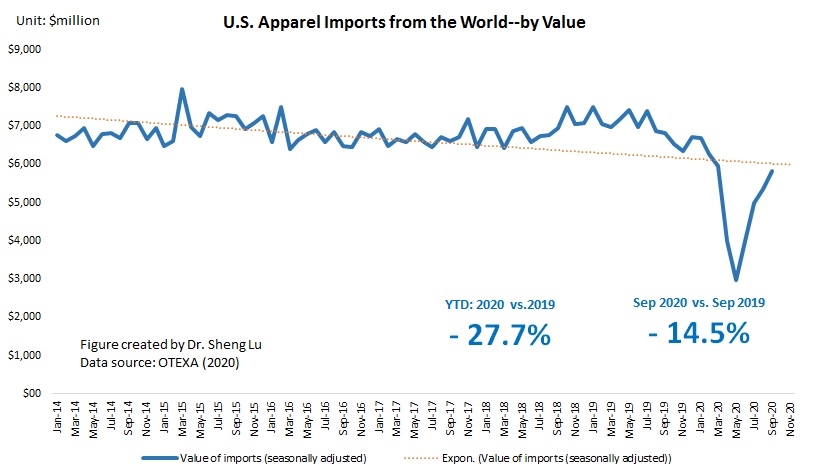

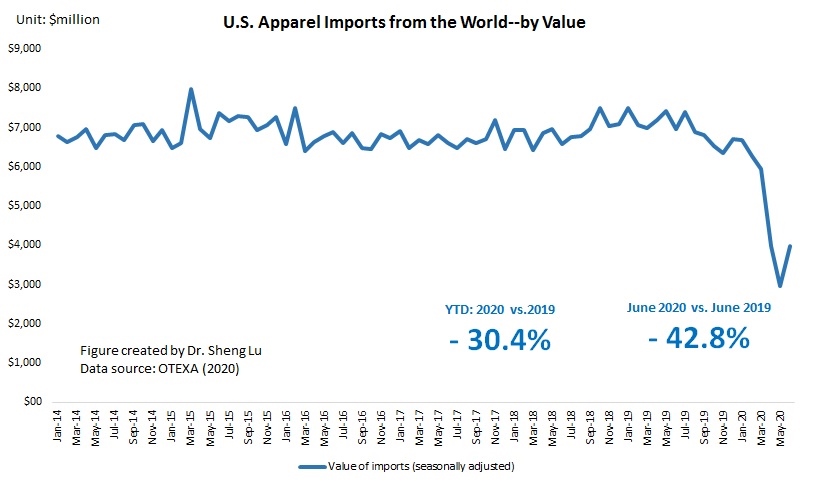

First, U.S. apparel imports continue to rebound thanks to consumers’ robust demand. However, the speed of recovery slowed. Specifically, The value of U.S. apparel imports in November 2020 marginally went down by 0.3% from October 2020 (seasonally adjusted), compared with an 8.8% growth from Aug to September and a 4.6% growth from September to October (seasonally adjusted).

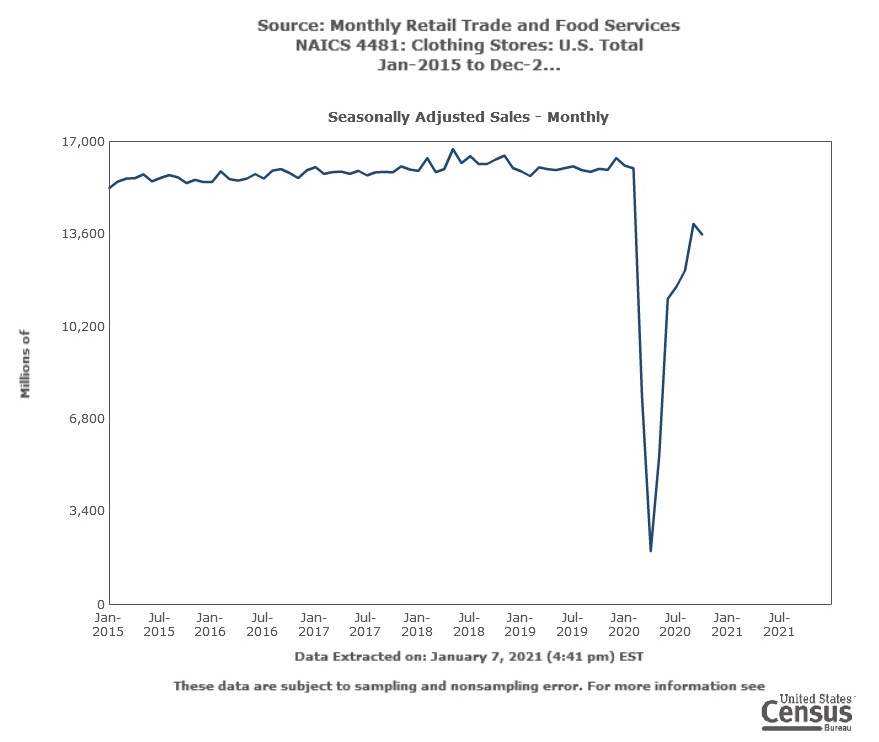

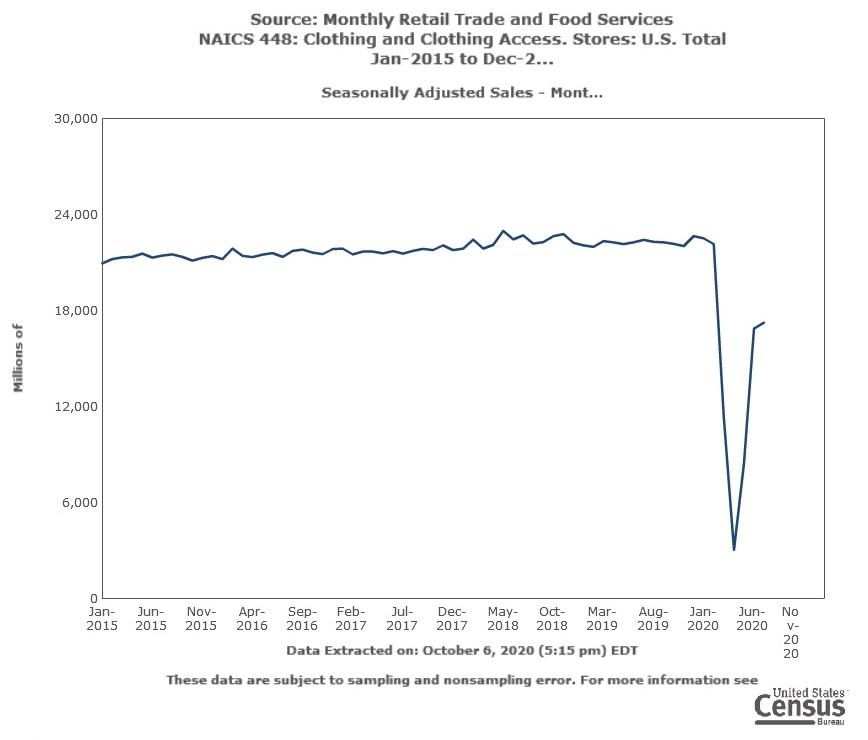

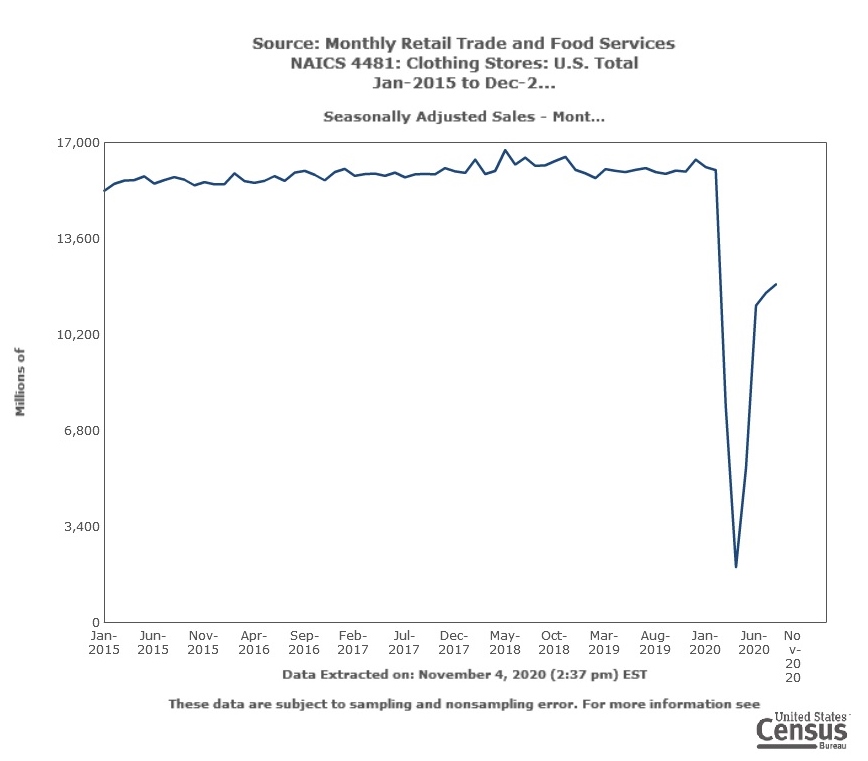

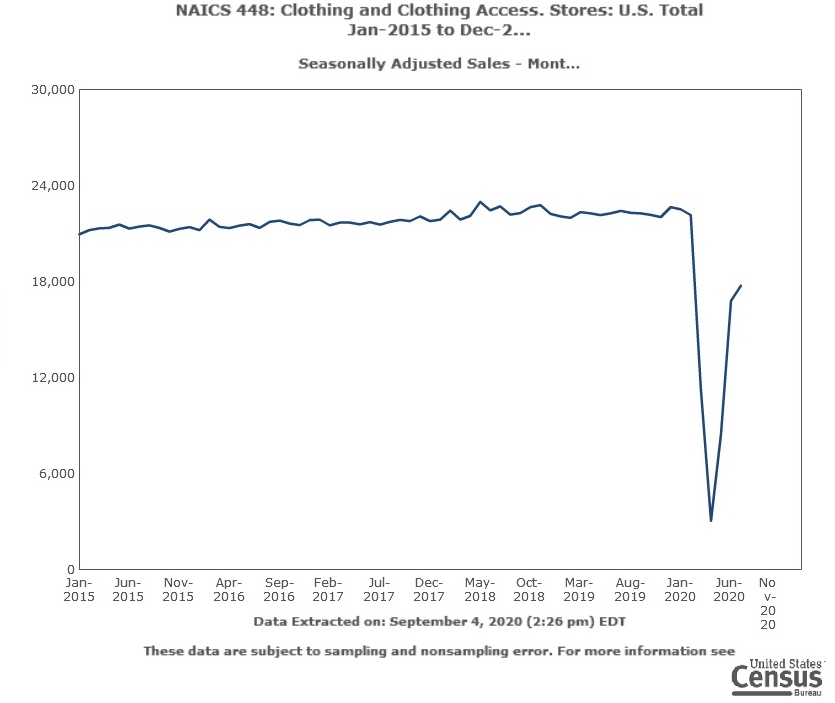

As of November 2020, the volume of U.S. apparel imports has recovered to around 85-90% of the pre-coronavirus level. This result echoes the trend of U.S. apparel retail sales (NAICS 4481), which also indicates a “V-shape” rebound since May 2020.

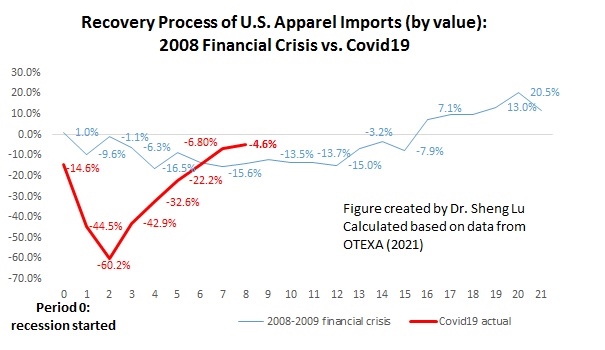

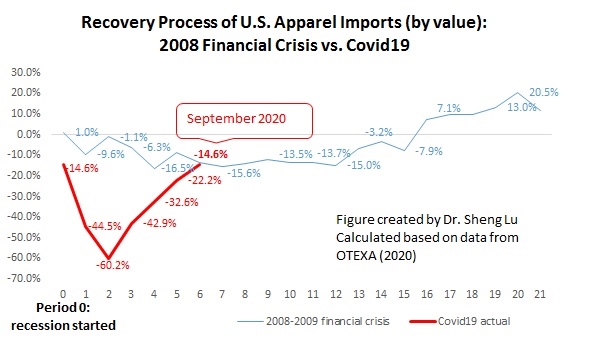

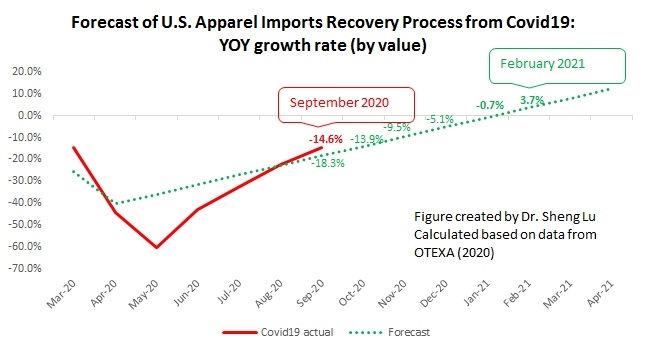

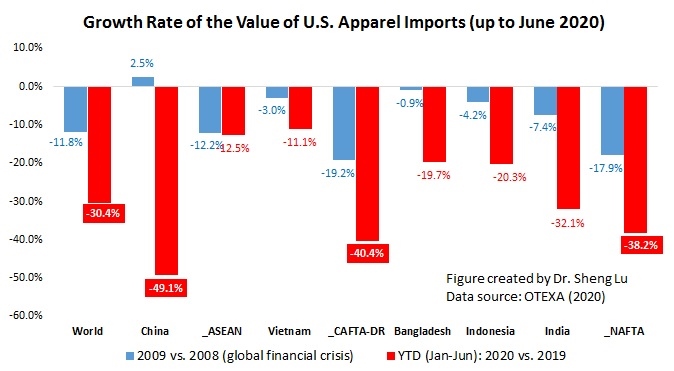

Data further shows that compared with the 2008 world financial crisis, Covid-19 has caused a more significant drop in the value of U.S. apparel imports. However, it seems the post-Covid recovery process has been more robust than the 2009 financial crisis. The Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model forecasts that at the current speed of recovery, the value of U.S. apparel imports (seasonally adjusted) could start to enjoy a positive year over year (YoY) growth by February 2021 (or around 11 months after the outbreak of Covid-19 in March 2020). In comparison, when recovering from the 2008 world financial crisis, it took almost 15 months to turn the YoY growth rate from negative to positive).

With the new lockdown measures taken in response to the resurgence of the Covid cases, the outlook of US apparel imports remains uncertain. It should also be noted that the period from December to April usually is the light season for apparel imports.

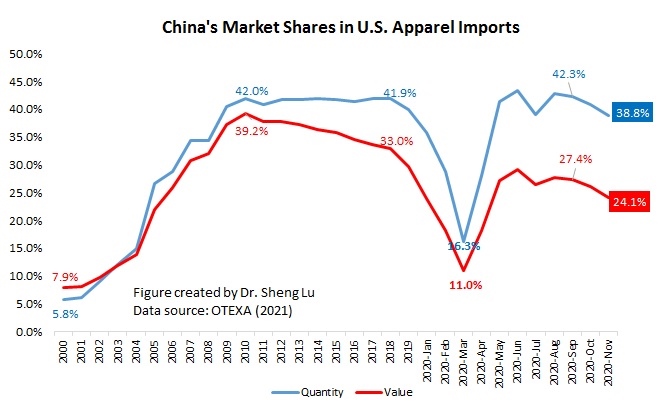

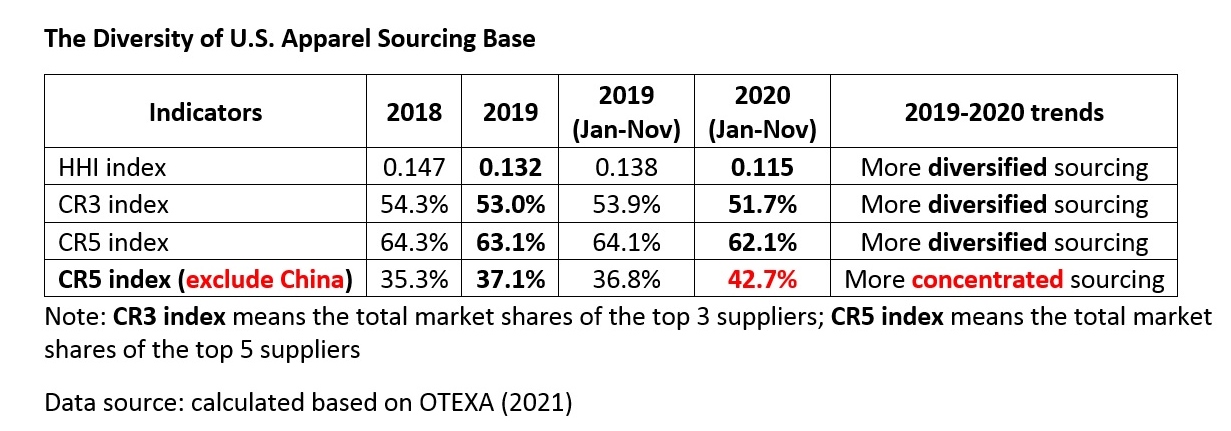

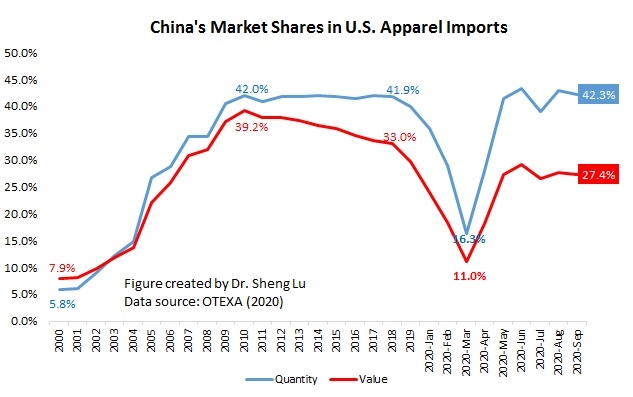

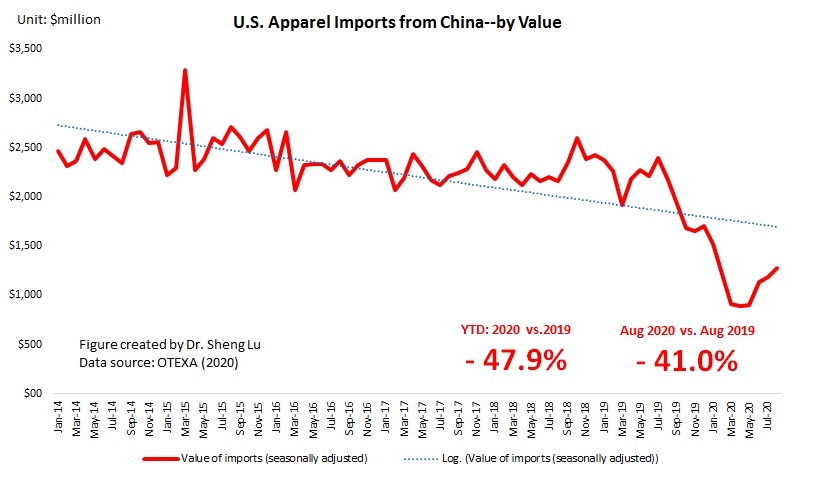

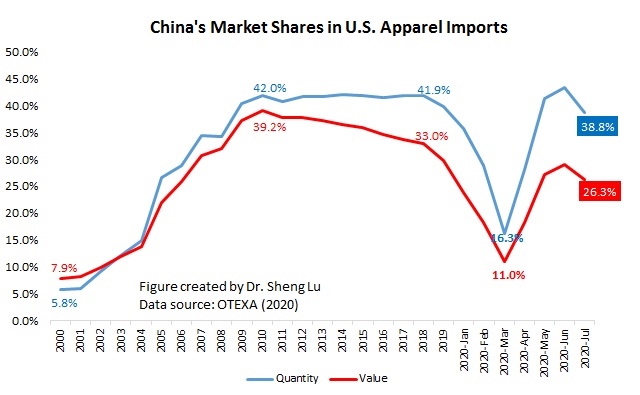

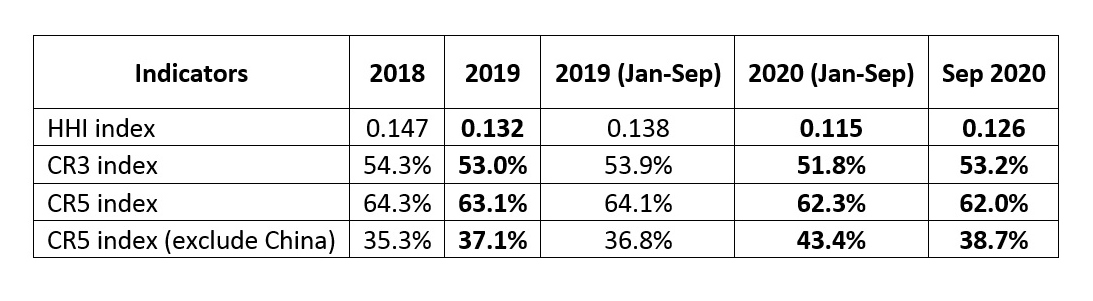

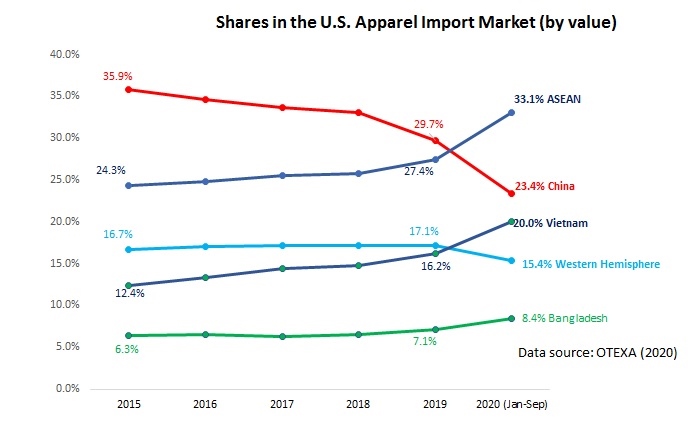

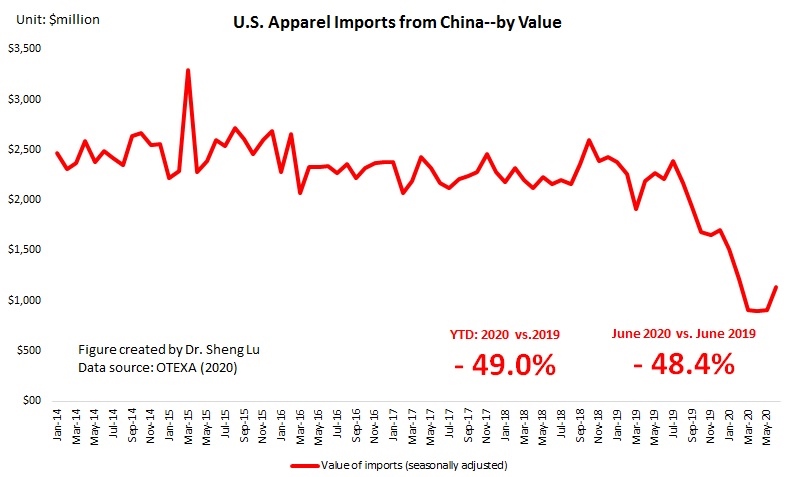

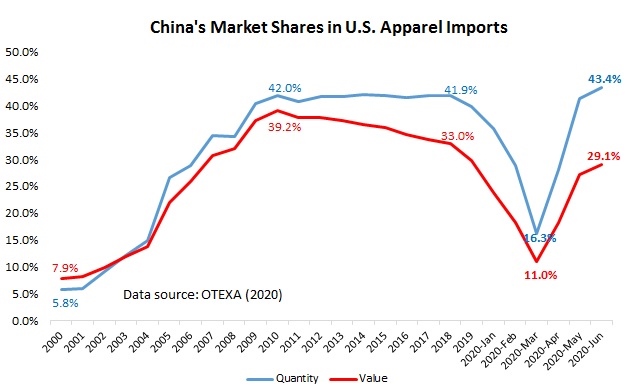

Second, supporting the findings of some recent studies, data suggests that U.S. fashion brands and retailers continue to reduce their “China exposure” in 2020. For example, both the HHI index and market concentration ratios (CR3 and CR5) suggest that apparel sourcing orders are gradually moving from China to other Asian countries. Related, since August 2020, China’s market shares in total U.S. apparel imports have been sliding both in quantity and in value.

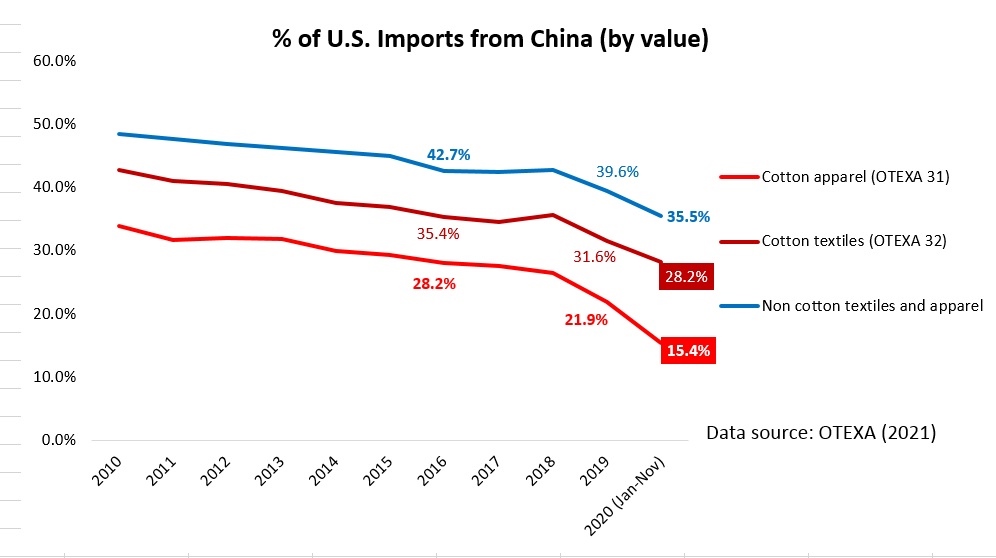

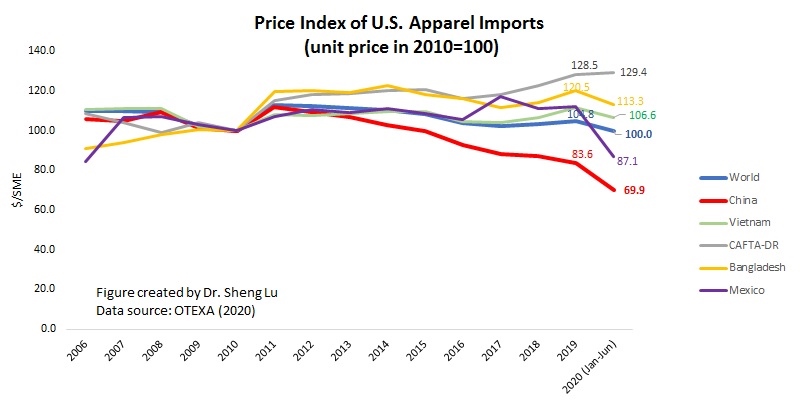

We should NOT ignore the impact of non-economic factors on China’s prospect as an apparel sourcing destination. For example, the reported forced labor issue related to Xinjiang, China, and a series of actions taken by the U.S. government (such as the CBP withhold release orders) have significantly affected U.S. cotton apparel imports from China. Measured by value, from January to November 2020, only 15.4% of U.S. cotton apparel came from China, compared with 22.2% in 2019 and 28% back in 2017. While China’s total textile and apparel exports to the US dropped by 32% in 2020 (Jan to Nov), China’s cotton textiles and cotton apparel exports to the US went down more sharply by 41.1% and 47.2%, respectively.

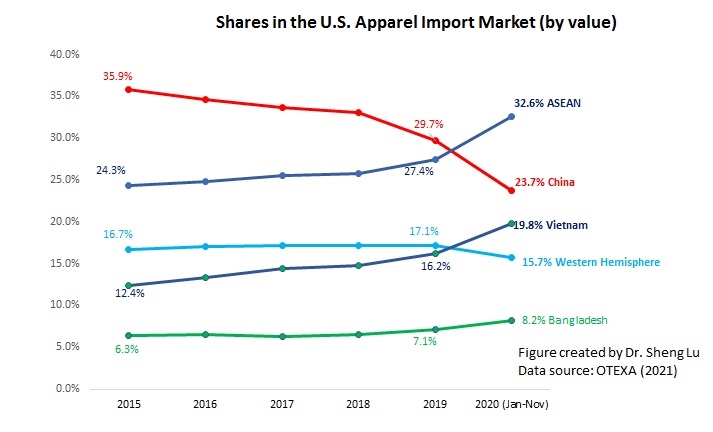

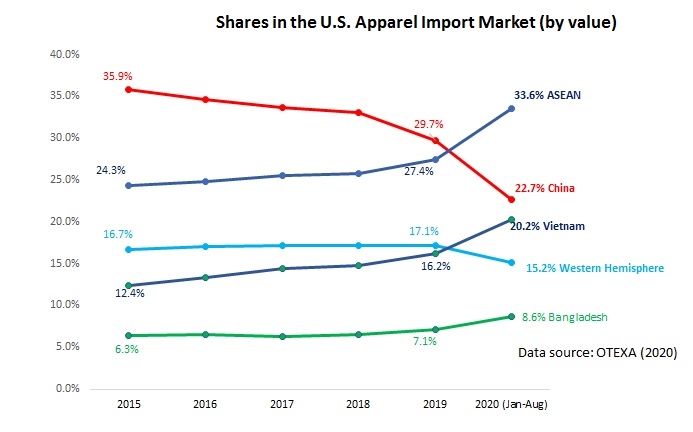

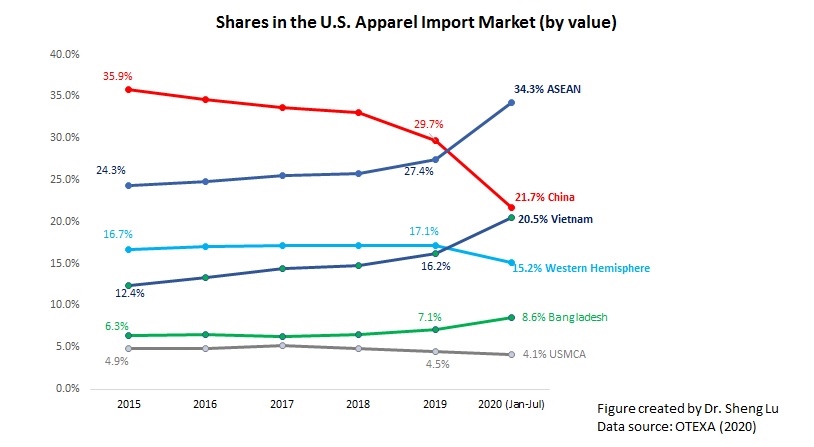

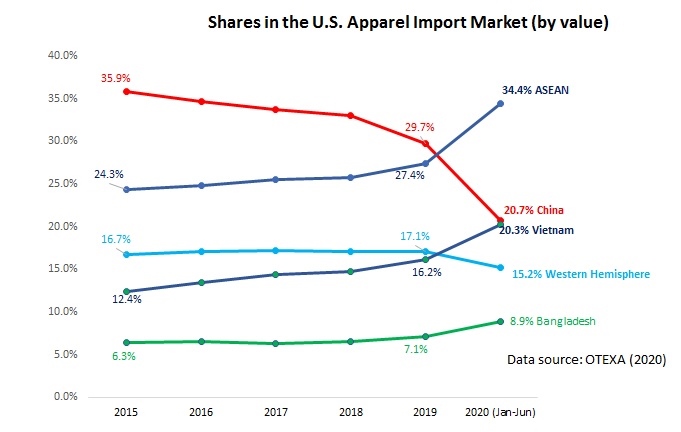

Third, despite Covid-19, Asia as a whole remains the single largest source of apparel for the U.S. market. Other than China, Vietnam (19.8% YTD in 2020 vs. 16.2% in 2019), ASEAN (32.6% YTD in 2020 and vs. 27.4% in 2019), Bangladesh (8.2% YTD in 2020 vs.7.1% in 2019), and Cambodia (4.4% YTD in 2020 vs. 3.2% in 2019) all gain additional market shares in 2020 (Jan to Nov) from a year ago.

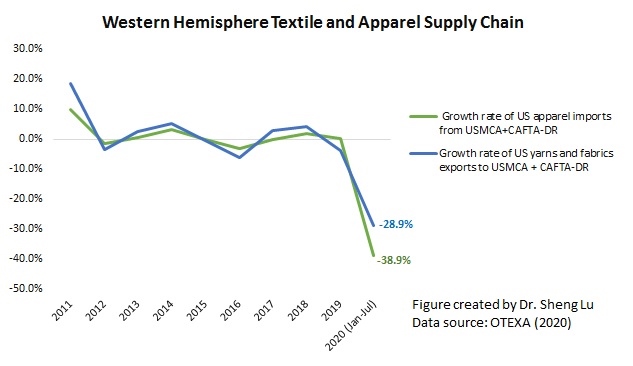

Fourth, still, no clear evidence suggests that U.S. fashion brands and retailers have been giving more apparel sourcing orders to suppliers from the Western Hemisphere because of COVID-19 and the U.S.-China tariff war. In the first eleven months of 2020, 9.4% of U.S. apparel imports came from CAFTA-DR members (down from 10.3% in 2019) and 4.4% from USMCA members (down from 4.5% in 2019). The limited local textile production capacity and the high production cost are the two notable disadvantages of sourcing from the region.

by Sheng Lu

TAL Apparel in response to COVID-19

About TAL Apparel

TAL Apparel is one of the world’s largest apparel companies, with over 70 years of history. Owned by Hong-Kong based TAL group, TAL Apparel employs about 26,000 garment workers in 10 factories globally, producing roughly 50 million pieces of apparel each year, including men’s chinos, polo tees, outerwear, and dress shirts. TAL Apparel claims it makes one in six dress shirts sold in the United States, including for well-known U.S. fashion brands such as Brooks Brothers, Bonobos, and LL Bean.

Other than owning factories in Asian countries such as Vietnam, China, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Thailand, TAL Apparel opened its first garment factory in Ethiopia in 2018 – based at the country’s flagship Hawassa Industrial Park. Among the reasons behind the decision is Ethiopia’s duty-free access to the US under the African Growth and Opportunity Act (AGOA), and to Europe under the Everything But Arms (EBA) initiative.

Discussion questions [Anyone is more than welcome to join our online discussions; For FASH455, please address at least two questions in your comment; please also mention the question number in your comment.]

- From TAL Apparel’s perspective, what are the major impacts of COVID-19 on the apparel industry, especially regarding sourcing and supply chain management? What are the key challenges apparel companies facing?

- How has TAL Apparel responded to COVID-19? What lessons can we learn from their experiences?

- From TAL Apparel’s story, how is the big landscape of apparel sourcing changing because of COVID-19?

- What long term business decisions apparel companies like TAL Apparel have to make, and what are your recommendations?

- Anything else you find interesting/intriguing/surprising/enlightening from the video?

Sourcing Strategy Comparison: EU VS. US Fashion Companies—Comments from Students in FASH455

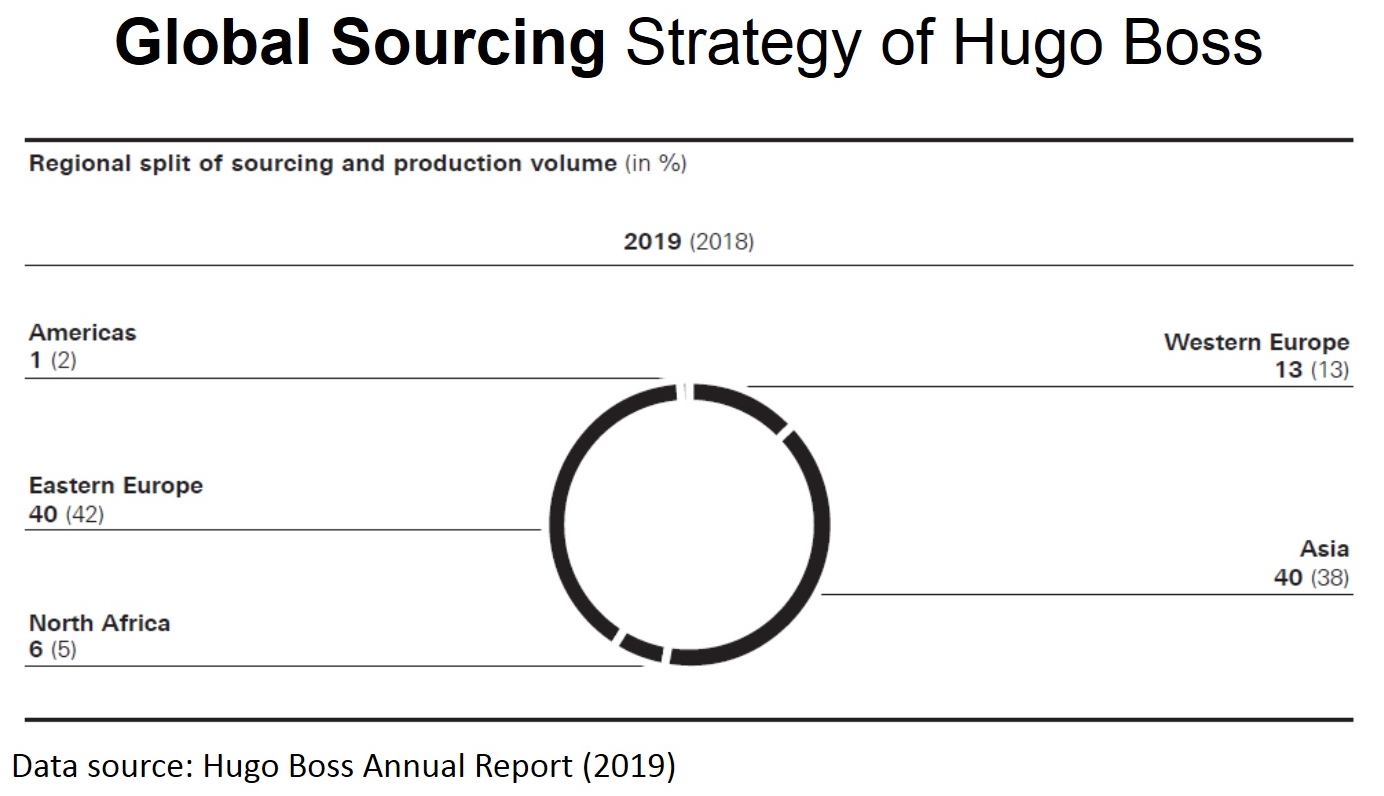

“Hugo Boss’s sourcing strategies are relatively different from fashion brands and retailers in the US. Hugo Boss’s self-owned production facilities are all located in Europe, and they follow the general trend of Eastern Europe being responsible for mass production items and Western Europe being responsible for more of the fine craftsmanship/made-to-measure items. Hugo Boss’s production distribution, which is 53% in Europe, 40% occurs in Asia, 6% in Africa, and 1% in the Americas, is much more diverse than the production distribution of the United States’ T&A industry, which heavily relies on Asian suppliers. It is indicative of a strong regional supply chain in Europe, and because the regional supply chain in the Americas is not as strong due to complicated trade agreements and lack of production capacity, many fashion brands and retailers heavily depend on overseas production from Asian countries. “

“I think that EU’s sourcing strategies are different from the U.S.’s sourcing strategy in the sense that it is kept within Europe. In the U.S., they are currently trying to bring the sourcing supply chain back to the Western Hemisphere, but it is very difficult for fashion brands to concede when sourcing is cheaper in Asia, and there is not enough labor who are trained for the work that they need. Over at the EU, with everything kept within the organization, it is a lot easier to find factories within different countries without reducing GDP since it is kept within the organization.”

“I think that one of the biggest differences between EU and US fashion brand’s sourcing strategies is the fact that there is a much higher luxury or high-end apparel market in the EU. Since they produce mostly luxury apparel products, they naturally place a lot more emphasis on the quality of their products being made rather than the quantity and speed of production. Since the US is more fast-fashion heavy, we do a lot more outsourcing of production so retailer’s are able to produce as many clothes as possible within a short period of time at a very low cost which is simply not achievable in many US clothing factories.”

“Hugo Boss pays close attention to where they are sourcing from and where each of their products should be made within their 4 production facilities. This stuck out to me because I don’t know how many US fashion brands have their own production facilities. I know a lot of brands outsource to countries like China and Bangladesh to factories who are also making clothing for many different brands.”

“EU has developed countries as well as developing countries, unlike the US. Western EU countries like Italy, France, UK and Germany are developed and focus more so on textile production. Whereas developing countries in the EU like Poland and Hungary focus more heavily on apparel manufacturing. In addition, unlike the US, the developed countries in EU also produce apparel exports, of high level, luxury goods.”

“It seems that in the EU the main focus is quality and social standards for these fashion brands and production. In the US, promoting local economic growth seems to be more of the focus of the free trade agreements. Sourcing for HUGO BOSS at least has strategically chosen factories where they can ensure quality checks and know how to conditions are. In the US, outside of the region, it seems that there are a lot of brands who do not know their secondary producers…”

“As the EU is more focused on production in high end markets than is the US, they (EU fashion companies) source more high-end quality fabrics. Progress has been made through technological advances, as the HUGO BOSS group developed the “smart factory” to further improve the quality of their fabrics and recognize any potential flaws before production. This stood out to me as a major difference, considering the US focuses on producing more fast-fashion goods and prioritizes high productivity overall quality garments. Also, they are more careful in their selection of suppliers and strive to build more long-term relationships with their suppliers. In comparision, most US fashion companies just try to produce as cheap and fast as possible through a short-term transctional-based importer-vendor relationship.”

“I think the sourcing strategies are similar to the U.S. in the fact that they source from various countries, creating this sense of “Made in the World.” However, there are differences as well. HUGO BOSS uses their own production facilities in addition to sourcing from other countries which is something we do not see often in the US. In fact, most brands and retailers in the US do not have their own production facilities or vertical supply chain, but instead source from overseas. Additionally, HUGO BOSS carefully selects their suppliers and immediately focus on social responsibility. US sourcing strategies seem to emphsis more on finding a factory with the lowest labor costs. EU brands and retailers, on the other hand, test their suppliers with test orders before selecting them as a supplier for the brand, and immediately develop social responsibility practices, such as trainings and building relationships. In the US, brands and retailers tend to focus on social responsibility in response to bad press and typically do so by a top-down approach.”

“The sourcing strategy in the Europe cares more about social impact. Retailers and brands there promote and educate their suppliers to be sustainable and take over their social responsibility. Another one is the European fashion retailers and brands are more likely to locate their product facilities within the Europe. Since the Europe does have a relatively stable and complete supply chain, the retailers and brands are able to saving transportation cost and expand the lead time. Third, the technology becomes an important factors for retailers and brands to consider. They are attempting to utilize technology to enhance the performance and their production process. “

“Hugo Boss strives to be the most desirable fashion and lifestyle brand in the premium sector. This shows in their emphasis on design, comfort, fit, and durability, as well as being mindful of their social and environmental impacts. They maintain long term relationships with a careful selection of suppliers, demand social compliance, and stay up to date with their “smart factory” aka AIs to speed up production and quality. They also source heavily from Asia, but also developed countries such as Italy and Germany. These values and practices are manifested in American brands, however, I believe we aren’t as extensive with sourcing from developed countries (such as Italy). From what I have learned thus far, it seems we source from countries close by and/or developing, but not so much mingling with luxury known countries, such as France or Italy (and if we do, the prices are expensive, and American customers don’t want to pay higher prices). We (US), too, source heavily from Asia, because it is cheap, and still focus internally on our own country when it comes to being more competitive in technological advancements. American and EU consumers alike value transparency in the clothing brands they buy from, and American brands are mindful of this, too. I would say we are more alike than different.”

[Please feel free to critique the comments above and join our online discussion]

Related readings

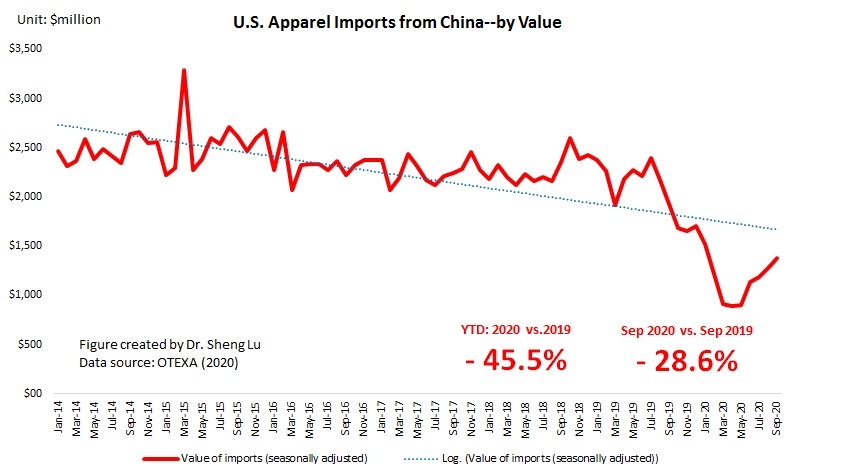

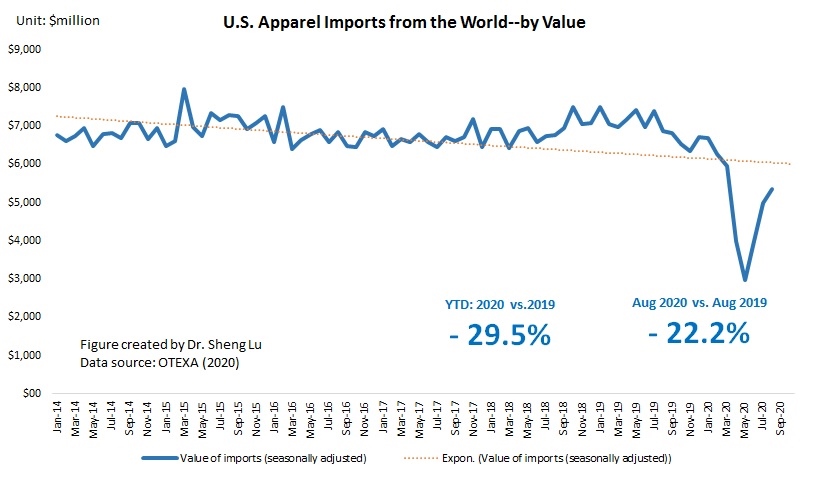

COVID-19 and U.S. Apparel Imports: Key Trends (Updated: November 2020)

First, U.S. apparel imports continue to rebound thanks to consumers’ robust demand. The value of U.S. apparel imports in September 2020 went up by 8.8% from August 2020 (seasonally adjusted), a new record high since March 2020 when COVID-19 broke out in the States. As of September 2020, the volume of U.S. apparel imports has recovered to around 84-85% of the pre-coronavirus level. This result echoes the trend of U.S. apparel retail sales (NAICS 4481), which also indicates a “V-shape” rebound since May 2020. As fashion brands and retailers typically build their inventory for holiday sales (such as back to school, Thanksgiving, and Christmas) from July to October, the upward trend of U.S. apparel imports hopefully will last for another 1-2 months.

Data also shows that compared with the 2008 world financial crisis, Covid-19 has caused a more significant drop in the value of U.S. apparel imports. However, it seems the post-Covid recovery process has been more robust than the 2008 financial crisis. Notably, the Auto Regressive Integrated Moving Average (ARIMA) model forecasts that at the current speed of recovery, the value of U.S. apparel imports (seasonally adjusted) could start to enjoy a positive year over year (YoY) growth by February 2021 (or around 11 months after the outbreak of Covid-19 in March 2020). In comparison, when recovering from the 2008 world financial crisis, it took almost 15 months to turn the YoY growth rate from negative to positive.

Second, still, no evidence suggests that U.S. fashion companies are giving up China as one of their essential apparel-sourcing bases. Notably, since May 2020, China had quickly regained its position as the top apparel supplier to the U.S. market. From June to September 2020, China’s market shares have stably stayed at around 27-28% in value and 40-42% in quantity.

According to the media, some sourcing orders are returning to China as China’s competitors in Asia are struggling with more limited production capacity, shortage of raw material and supply chain disruption caused by Covid-19.

That being said, trade data suggests that U.S. fashion companies continue to reduce their “China exposure” overall. For example, both the HHI index and the market concentration ratios (CR3–total market shares of top 3 suppliers and CR5–total market shares of top 5 suppliers) indicate that apparel sourcing orders are gradually moving from China to other Asian countries–it is interesting to see HHI, CR3 and CR5 all suggest a more diversified apparel sourcing base in 2020 (Jan-Sep) than in 2018 and 2019; however, the value of CR5 (exclude China) reached a new record high in 2020 (Jan-Sep).

Third, related to the point above, despite Covid-19, Asia as a whole remains the single largest source of apparel for the U.S. market. Other than China, Vietnam (20.0% YTD in 2020 vs. 16.2% in 2019), ASEAN (33.1% YTD in 2020 and vs. 27.4% in 2019), Bangladesh (8.4% YTD in 2020 vs.7.1% in 2019), and Cambodia (4.4% YTD in 2020 vs. 3.2% in 2019) all gain additional market shares in 2020 from a year ago.

Fourth, still, no clear evidence suggests that U.S. fashion brands and retailers have been giving more apparel sourcing orders to suppliers from the Western Hemisphere because of COVID-19 and the trade war. In the first nine months of 2020, only 9.1% of U.S. apparel imports came from CAFTA-DR members (down from 10.3% in 2019) and 4.4% from USMCA members (down from 4.5% in 2019). Confirming the trend, in the first nine months of 2020, the value of U.S. yarns and fabrics exports to USMCA and CAFTA-DR members also suffered a 26% decline from a year ago. The heavy reliance on textile supply from the U.S. (implying more vulnerability to the Covid-19 supply chain disruptions) and the price disadvantage could be among the major contributing factors.

Just an anecdote–according to some industry insiders, the booming of E-commerce during the pandemic may also possibly explain why “near sourcing” is not reflected in trade data despite its reported growing popularity. Specifically, US fashion retailers would:1) import products from Asia and stock them in the bonded warehouses in Mexico (note: bonded warehouse means dutiable goods may be stored, manipulated, or undergo manufacturing operations without payment of duty). 2) When US consumers place orders, the retailer will ship products directly from these bonded warehouses in Mexico to the final destination. Most importantly, retailers could take advantage of the US de minimis rule (i.e., goods valued at $800 or less could enter the U.S. duty-free one person one day) and avoid paying tariffs– even though these products are counted as imports from Asian countries that do not have a free trade agreement with the United States. In other words, these products are not officially treated as imports from Mexico even though they are shipped from bonded warehouse in Mexico.

by Sheng Lu

Battling the Trade War and COVID-19: Rethinking Global Supply Chains in a Time of Crisis

Speaker: Wilson Zhu, the Chief Operating Officer of Li & Fung

Event summary:

- The originator of the US-China trade war was not actually about the “trade deficit”, but rather a lack of “trust” between the two countries.

- Trade deficit could be a “misleading concept”–while the iPhone was claimed to be “Made in China”, it wasn’t manufactured there at all—instead, China only played the role of a “middle-man of the supply chain.” Such a misunderstanding is within the ancient country of origin rules used in international trade.

- The “Made in China” label is becoming “obsolete.” As China continues to expand its supply chain globally, ports in China are evolving into “managers” of products “Made in the world.”

- Despite the tariff war and the pandemic, interestingly enough, it seems some apparel sourcing orders are returning from India and Vietnam to China. Further, China’s emergence as a lucrative apparel consumption market implies huge business opportunities for fashion brands and retailers.

- There is still great hope for the global apparel supply chain in the post-Covid world. Less economically developed countries like Vietnam are now mimicking the former industrialization of China in its factories with the help of advanced technology. And, the United States continues to advance the efficiency and sophistication of its textile production. It seems that all in all, the only way to make it through this crisis successfully, is through global collaboration, not conflict.

(summarized by Andrea Attinello)

USMCA: Changes for the Textile and Wearing Apparel Industries

From findings of the 2020 USFIA Fashion Industry Benchmarking Study :

The surveyed U.S. fashion companies demonstrate more readiness and interest in using the US-Mexico-Canada Trade Agreement (USMCA) for apparel sourcing purposes in 2020 than a year ago:

For companies that were already using NAFTA for sourcing, the vast majority (77.8 percent) say they are “ready to achieve any USMCA benefits immediately,” up more than 31 percent from 2019.

Even for respondents who were not using NAFTA or sourcing from the region, about half of them this year say they may “consider North American sourcing in the future” and explore the USMCA benefits.

Nevertheless, when asked about the potential impact of USMCA on companies’ apparel sourcing practices, some respondents expressed concerns about the rules of origin changes. These worries seem to concentrate on denim products in particular. For example, one respondent says, “USMCA changes negatively affects our denim jeans sourcing particularly with the new pocketing rules of origin.” Another adds, “Denim pocketing ROO change is a concern but manageable.”

It also remains to be seen whether USMCA will boost “Made in the USA” fibers, yarns, and fabrics by limiting the use of non-USMCA textile inputs. For example, while the new agreement expands the Tariff Preference Level (TPL) for U.S. cotton/man-made fiber apparel exports to Canada (typically with a 100 percent utilization rate), these apparel products are NOT required to use U.S.-made yarns and fabrics.

Related readings:

New ILO Report: The supply chain ripple effect– How COVID-19 is affecting garment workers and factories in Asia and the Pacific

The full report is available HERE. Key findings:

1. The garment industry in the Asia-Pacific region is particularly vulnerable to the adverse impact of COVID-19 because of the size of the industry present and the high stakes involved. Notably, garment workers (over 60 million in total, including 35 million women) accounted for 21.1% of the manufacturing employment in the region as of 2019. Over 60% of the world’s apparel exports currently come from the Asia-Pacific region.

2. The cumulative impacts of COVID-19 on garment supply chains have been both far-reaching and complex: 1) As of September 9, 2020, more than 31 million garment workers in the Asia Pacific region were still affected by factory closure (i.e., mandatory closures of non-essential workplaces). 2) The drop in consumer demand and the decline in retail sales in the primary apparel consumption markets across the world have affected garment workers in the Asia-Pacific region negatively. As of September 9, 2020, 49% of all jobs in the Asia-Pacific garment supply chains (29 million) were dependent on demand for garments from consumers living in countries with the most stringent lockdown measures in place. Another 31 million jobs (51%) depended on consumer demand that is based in countries with a medium level of lockdown measures in place. 3) COVID-19 has further caused supply chain disruptions and prevented imported inputs into garment production from arriving in time. The heavy reliance on textile raw material supply from China makes many apparel producing countries in South-East Asian countries highly vulnerable to shortages of inputs.

3. The world apparel trade has fallen in the first half of 2020 sharply. This includes a 26% YoY drop in the US, a 25% drop in the EU, and a 17% drop in Japan. However, the timing and magnitude of these import declines vary significantly — China’s exports started to drop first at the beginning of the year,2020. Then, the exports from Vietnam, Bangladesh, Indonesia, and India began to decrease also since February (a joint effect of the shortage of raw material + decreased import demand). Data further shows that the drop in world apparel trade has been more significant than other products in the first half of 2020.

4. Apparel suppliers in the Asia Pacific region have been struggling with order cancellations AND longer payment terms insisted on by Western fashion brands and retailers. Garment factories say that they don’t have the leverage to ‘push back’ against these changes to contract terms and buyer policies.

5. Thousands of garment factories in the Asia-Pacific region closed at least temporarily because of COVID-19, some of them indefinitely. For example, In Cambodia, approximately 15-25% of factories had no orders at the end of the June 2020. Likewise, around 60% of garment factories in Bangladesh reported closing for more than 3 weeks. Related, layoffs have been widespread. For example, according to Indonesia’s Ministry of Industry, approximately 30% of their apparel and footwear workforce had been laid-off by July 2020 (812,254 in total). In Cambodia, approximately 15% of their garment workers (more than 150,000 workers) were reported to have lost their jobs during the pandemic. Further, garment factories have been operating at reduced capacity during the pandemic. For example, in Bangladesh, as of July 2020, the proportion of workers returning to work after re-opening was only 57% of the pre-pandemic level. Similarly, in Vietnam, as of July 2020, the proportion of workers returning to work after re-opening was also just around 50% of the pre-pandemic level.

Related reading:

- International Textile Manufacturers Federation (ITMF) 5th Covid impact survey (September 2020)

- World trade by sector (including textiles and clothing) in Q2 2020 (World Trade Organization)

- USFIA 2020 Fashion Industry Benchmarking Study (US fashion brands and retailers’ response to the COVID as of July 2020)

- What next for Asian garment production after COVID-19? The perspectives of industry stakeholders (ILO, September 2020)

COVID-19 and U.S. Apparel Imports: Key Trends (Updated: October 2020)

First, U.S. apparel imports continue to rebound thanks to consumers’ robust demand. The value of U.S. apparel imports in August 2020 went up by 7.6% from July 2020 (seasonally adjusted), a new record high since March 2020 when COVID-19 broke out in the States. As of August 2020, the volume of U.S. apparel imports has recovered to around 80% of the pre-coronavirus level. This result echoes the trend of U.S. apparel retail sales (NAICS 448), which also indicates a “V-shape” rebound since May 2020. As fashion brands and retailers typically build their inventory for holiday sales (such as back to school, Thanksgiving, and Christmas) from July to October, the upward trend of U.S. apparel imports hopefully will last for another 1-2 months.

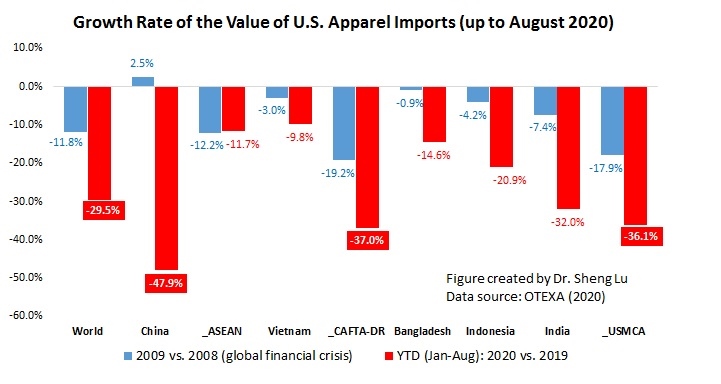

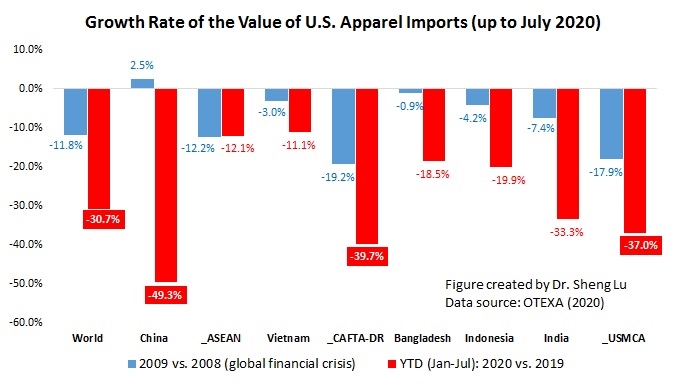

Nevertheless, between January and August 2020, the value of U.S. apparel imports decreased by almost 30% year over year, which has been MUCH worse than the performance during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (down 11.8%).

Second, no evidence suggests that U.S. fashion companies are giving up China as one of their essential apparel-sourcing bases. Notably, since May 2020, China had quickly regained its position as the top apparel supplier to the U.S. market. From June to August 2020, China’s market shares have stably stayed at around 27-28% in value and 40-42% in quantity.

Some industry sources show that “Made in China” enjoys two notable advantages that other apparel supplying countries cannot catch up in the short term. 1) unparalleled production capacity, meaning importers can source almost all products in any quantity from China vs. more limited production capacity (both in terms of variety and volume) in other alternative sourcing destinations. 2) China can mostly produce textile raw material locally vs. many apparel exporting countries still rely heavily on imported yarns and fabrics (supplied by China).

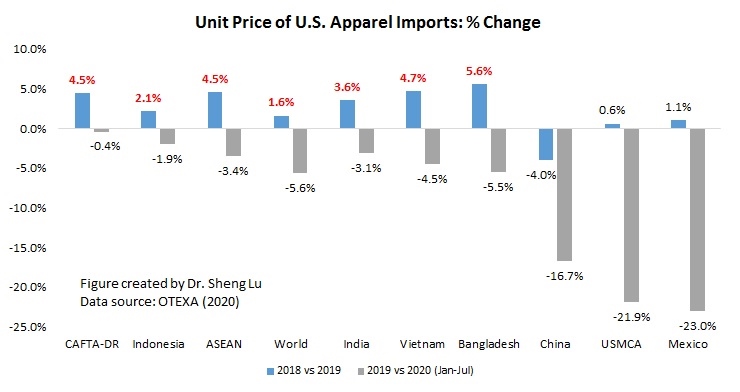

However, non-economic factors, particularly the reported Xinjiang forced labor issue, are complicating fashion companies’ sourcing decisions. Notably, US cotton apparel imports from China year-to-date (YTD) in 2020 (Jan to August) significantly decreased by 54% from a year ago, much higher than the 22% drop in US imports from the rest of the world. As a result, China’s market share in the US cotton apparel import market sharply declined from 22% in 2019 to only 15.1% in 2020 (Jan-Aug), a record low in the past ten years. This unusual trade pattern suggests that the concerns about social compliance risk are holding US fashion companies back from sourcing cotton apparel products from China. As the forced labor issue continues to evolve and become ever more sensitive and high profile, it is not unlikely that US fashion companies may substantially cut their China sourcing further, even if it is not a preferred choice economically.

Third, despite Covid-19, Asia as a whole remains the single largest source of apparel for the U.S. market. Other than China, Vietnam (20.2% YTD in 2020 vs. 16.2% in 2019), ASEAN (33.6% YTD in 2020 and vs. 27.4% in 2019), Bangladesh (8.6% YTD in 2020 vs.7.1% in 2019), and Cambodia (4.5% YTD in 2020 vs. 3.2% in 2019) all gain additional market shares in 2020 from a year ago.

Likewise, thanks to a highly integrated regional textile and apparel supply chain, Asian countries all together were able to maintain fairly stable market shares on the world stage over the past decade despite all market disruptions, from the financial crisis, trade war to the wage increase.

Fourth, still, no clear evidence suggests that U.S. fashion brands and retailers have been giving more apparel sourcing orders to suppliers from the Western Hemisphere because of COVID-19 and the trade war. In the first seven months of 2020, only 8.9% of U.S. apparel imports came from CAFTA-DR members (down from 10.3% in 2019) and 4.1% from USMCA members (down from 4.5% in 2019). Confirming the trend, in the first eight months of 2020, the value of U.S. yarns and fabrics exports to USMCA and CAFTA-DR members also suffered a 28.0% decline from a year ago. The heavy reliance on textile supply from the U.S. (implying more vulnerability to the Covid-19 supply chain disruptions) and the price disadvantage could be among the contributing factors.

Further, industry sources show that the apparel products U.S. fashion companies import from members of USMCA and CAFTA-DR predominantly are tops and bottoms. The lack of production capacity for other product categories significantly limits the growth potential of these countries playing the role as a leading sourcing base.

by Sheng Lu

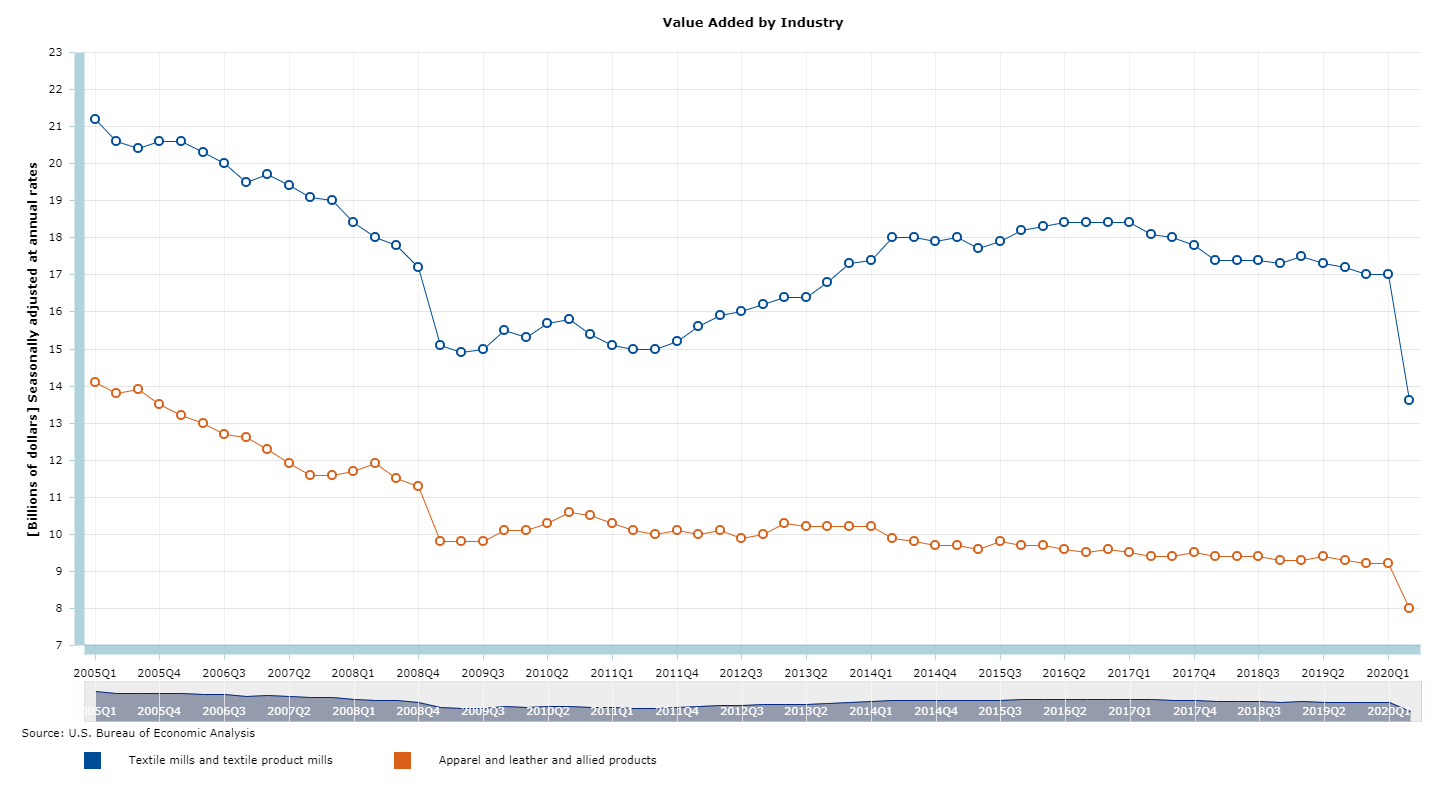

State of the U.S. Textile and Apparel Industry: Output, Employment, and Trade (Updated October 2020)

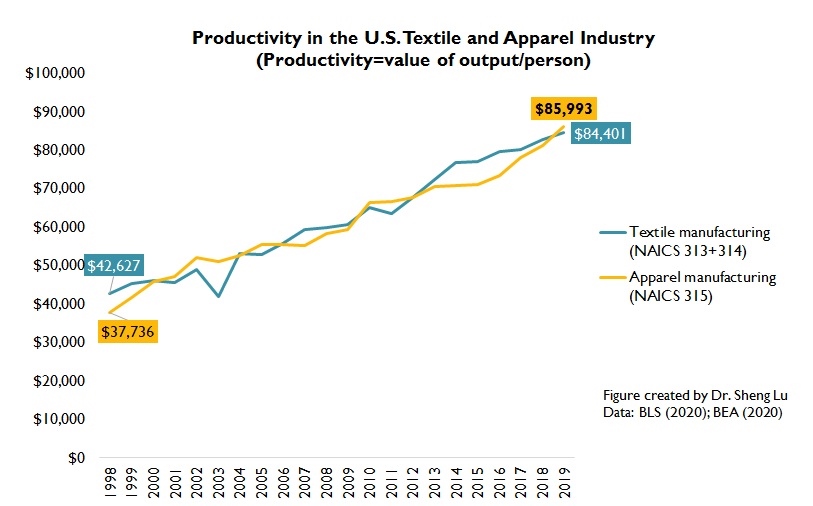

The size of the U.S. textile and apparel industry has significantly shrunk over the past decades. However, U.S. textile manufacturing is gradually coming back. The output of U.S. textile manufacturing (measured by value added) totaled $18.79 billion in 2019, up 23.8% from 2009. In comparison, U.S. apparel manufacturing dropped to $9.5 billion in 2019, 4.4% lower than ten years ago (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2020).

Meanwhile, COVID-19 has hit U.S. textile and apparel production significantly. Notably, the value of U.S. textile and apparel output decreased by as much as 21.4% and 14.9% in the second quarter of 2020, respectively, compared with a year ago. This result was worse than a 15% decrease during the 2008-2009 world financial crisis. Further, the decline in U.S. textile exports is an essential factor contributing to the significant drop in U.S. textile manufacturing. In the first seven months of 2020, the value of U.S. yarn and fabric exports went down by 31% and 19%, respectively, year over year (OTEXA, 2020).

Additionally, as the U.S. economy is turning more mature and sophisticated, the share of U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing in the U.S. Gross Domestic Product (GDP) dropped to only 0.13% in 2019 from 0.57% in 1998 (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2020).

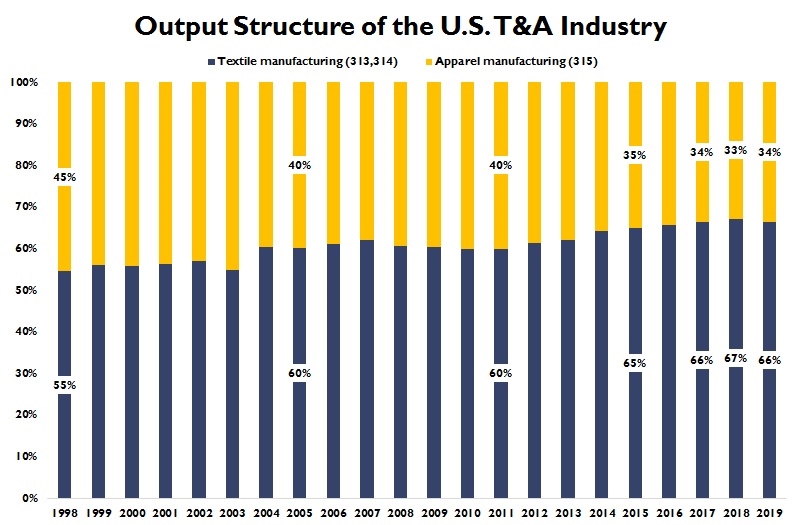

The U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing is also changing in nature. For example, textile products had accounted for over 66% of the total output of the U.S. textile and apparel industry as of 2019, up from 58% in 1998 (Bureau of Economic Analysis, 2020). Textiles and apparel “Made in the USA” are growing particularly fast in some emerging markets that are high-tech driven, such as medical textiles, protective clothing, specialty and industrial fabrics, and non-woven.

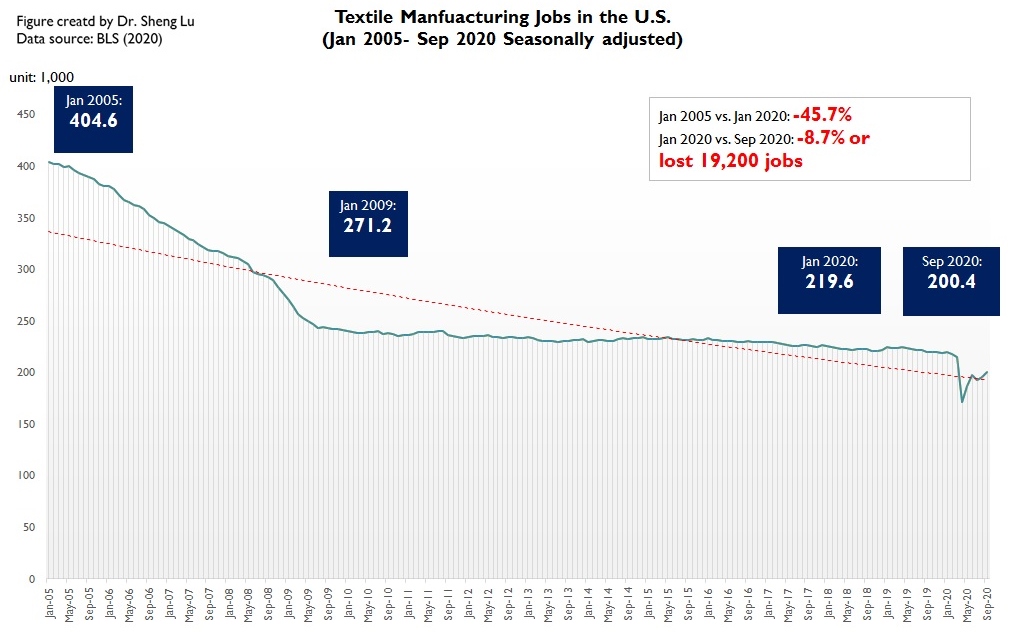

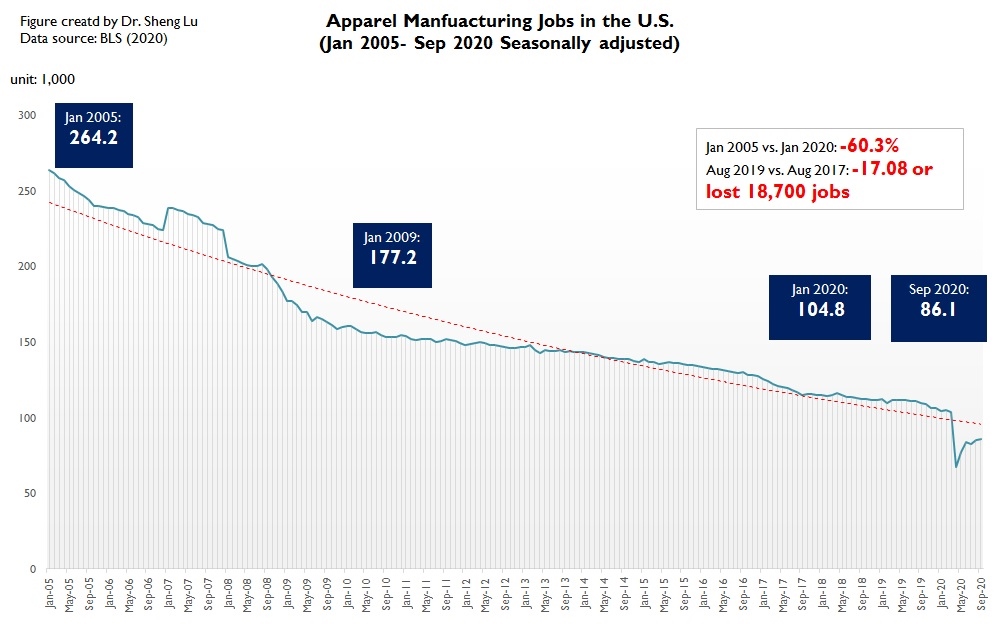

As production turns more automated, the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector is NOT creating more jobs. Even before the pandemic, from January 2005 to January 2020, employment in the U.S. textile manufacturing (NAICS 313 and 314) and apparel manufacturing (NAICS 315) declined by 44.3% and 59.3%, respectively (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2020). However, improved productivity (i.e., the value of output per employee) could be a critical factor behind the net job losses.

Data further shows that COVID19 has resulted in more than 83,700 job losses in the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector between March-April 2020, of which around 80% have returned as of September 2020. Nevertheless, the downward trend in employment is not changing for the U.S. textile and apparel manufacturing sector.

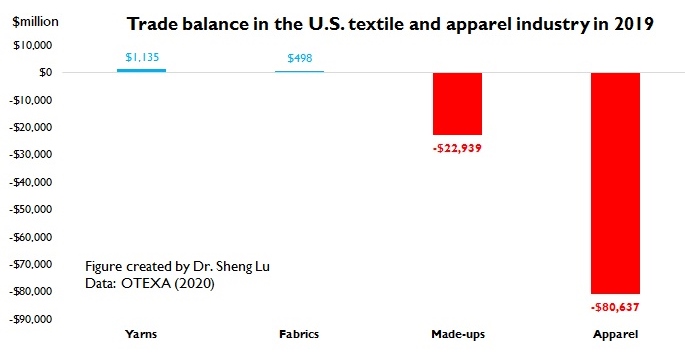

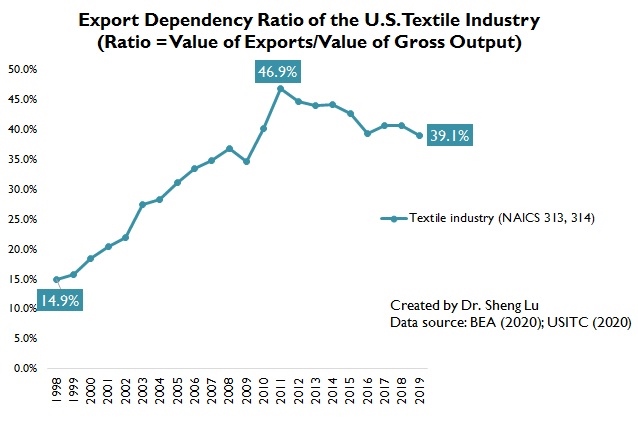

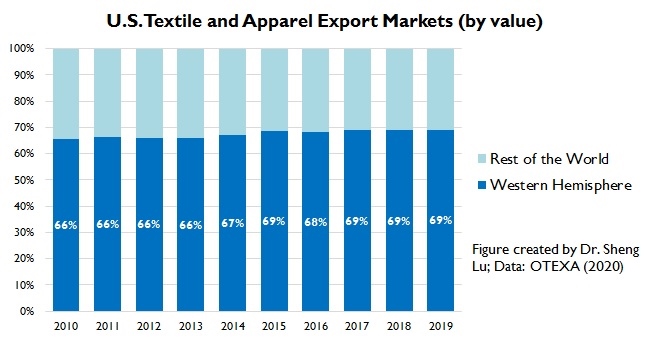

Consistent with the theoretical prediction, U.S. remains a net textile exporter and a net apparel importer. In 2019, the U.S. enjoyed a $1,633million trade surplus in textiles and suffered an $80,637 million trade deficit in apparel (USITC, 2020). Notably, nearly 40% of textiles “Made in the USA” (NAICS 313 and 314) were sold overseas in 2019, up from only 15% in 2000 (OTEXA, 2020). On the other hand, because of the regional supply chain, close to 70% of U.S. textile and apparel export go to the western hemisphere, a pattern that stays stable over the past decade.

by Sheng Lu

Discussion questions:

- Why or why not do you think the U.S. textile industry (NAICS 313 +314) and the apparel industry (NAICS 315) are in good shape?

- Based on the statistics, do you think textile and apparel “Made in the USA” have a future? Please explain.

- What are the top challenges facing the U.S. textile industry and the apparel industry in today’s global economy and during the COVID19?

What A Vertically-Integrated Textile and Apparel Factory Looks Like Today

Discussion questions (For FASH455, please answer all questions):

- From the video, how is textile manufacturing (e.g., yarns and fabrics) different from apparel manufacturing?

- Based on our lectures and the video, how do you see the impact of automation on shaping the future landscape of world textile and apparel production and trade?

- Will you be interested in working for a textile/apparel factory after graduation? Why or why not?

Examine the US-China Tariff War from a Theoretical Perspective: Discussion Questions from Students in FASH455

#1 In class, we discussed that trade always creates both winners and losers. So who are the winners and losers in the US-China tariff war? Also, why should or should not the government use trade policy to pick up winners and losers in international trade?

#2 Why do you think U.S. fashion brands and retailers oppose Section 301 tariffs on apparel imports from China, whereas the National Council of Textile Organizations (NCTO), which represents the US textile industry, supports Trump’s tariff action?

#3 The U.S.-China tariff war continues during the pandemic, resulting in higher sourcing costs for U.S. fashion brands and retailers, which have been struggling hard financially. In such a case, if you were the CEO of Macy’s, why or why not would you pass the tariff burden to consumers, i.e., ask consumers to pay a higher price?

#4 Why or why not do you agree with the Trump Administration to lift the Section 301 tariffs on PPE imports from China? Isn’t a high tariff typically protects the domestic industry and would incentivize more U.S.-based PPE production?

#5 Most classic trade theories (such as the comparative advantage trade theory and the factor proportion trade theory) advocate free trade with no government interventions. However, international trade in the real world has been so heavily influenced by government policy, such as tariffs. How to explain this phenomenon? Are trade theories wrong, or is the government wrong?

[Anyone is welcome to join the online discussion. For students in FASH455, please address at least two questions in your comment. Please also mention the question number in your comment]

FASH455 Exclusive Interview with Jason Prescott, CEO of Apparel Textile Sourcing Trade Shows

Guest Speaker: Jason Prescott

Jason Prescott founded JP Communications INC in 2005 and rapidly established TopTenWholesale.com and Manufacturer.com as the largest US-based B2B global trade network for manufacturers, retailers, department stores, discounters, importers, wholesalers, buyers and brands. A decade later, in 2016, he established the Apparel Textile Sourcing trade show platform with the China Chamber of Commerce for Import & Export of Textile & Apparel to connect the global B2B network of over 2 million with manufacturers around the globe via in-person events. By 2020, the ATS brand has created the fastest-growing trade shows in the industry producing annual events in Miami, Toronto, Montreal, Berlin and virtually.

Jason is active in search marketing models and technology and provides consulting and seminars in around the world for organizations looking to invest in the USA market. He is the author of two best-selling books, Wholesale 101 and Retail 101, published by McGraw Hill as well as articles on business and technology appearing in B2B Online, Omma, IMediaConnection, CEO Magazine, Entrepreneur Online, and been cited in Inc Magazine, Business Week and Forbes Online.

Moderator: Kendall Keough

Kendall Keough is a recent graduate from the University of Delaware (UD) with a Master of Science in Fashion & Apparel Studies. She also graduated from the UD with a Bachelor’s Science in Fashion Merchandising & Honors in 2019. Kendall was a recipient of the 2018 YMA Fashion Scholarship Fund national case study competition. While studying at UD, she also held several leadership positions, including serving as the President of the Synergy Fashion Group between 2018 and 2019. Kendall is the author of several recent papers addressing the U.S. textile and apparel industry and related trade issues, including: Explore the export performance of textiles and apparel “Made in the USA”: A firm-level analysis. (Journal of the Textile Institute, 2020); US-Kenya trade deal – Here’s what the apparel industry wants (Just-Style, 2020); ‘Made in the USA’ textiles and apparel – Key production and export trends (Just-Style, 2020).

Interview highlights

Kendall: What has motivated you to get involved in the apparel business, especially running the Apparel Textile Sourcing Trade (ATS) Shows, which has grown into one of the most popular and influential sourcing events today?

Jason: We started our company in 2005 w/ our flagship product – www.TopTenWholesale.com – which is a search engine for wholesale suppliers and products. In 2010 we acquired www.manufacturer.com – a sourcing platform to find global producers and manufacturers. It would be fair to say that never in our wildest imagination did we think we would be producing some of the world’s top sourcing trade fairs in the apparel and textile industry. I’d like to say it was a natural evolution but to be frank the opportunity came up over a cup of tea with a very good friend of mine, Mr. Chen Zhirong – Director for the China Chamber of Commerce for Import & Export of Textiles (CCCT) – in Dec 2015. What started from a cup of tea wound up growing into a trade show company that now produces events 4 cities, 3 countries and 2 continents (Miami, Toronto, Montreal, Berlin).

More than 200 of the world’s top producers of apparel, textiles, accessories, footwear, and personal protective equipment will exhibit virtually at Apparel Textile Sourcing trade shows this fall. Attendance is always free and the interactive event also specializes in seminars, sessions, workshops and panels from experts in the industries of sourcing, fashion, design and retail.

Kendall: COVID-19 is the single biggest challenge facing the textile and apparel industry today. From your observation, how has COVID-19 affected textile and apparel companies’ sourcing practices? What will be the medium to the long-term impact of COVID on textile and apparel sourcing?

Jason: The fallout from the pandemic – particularly in the textile and apparel industry – and how it impacts sourcing, has had such a far-reaching magnitude that it’s still very challenging to figure out how sourcing practices will be impacted. Over the long term, there is no question that this pandemic will speed up near-sourcing, on-shoring, digitization, and real-time production. The interim has resulted in massive layoffs, geo-political uncertainty and a turbulent political atmosphere that has rattled the cages of just about every sourcing director. The industry has seen purchase orders defaulted on, behavior in the supply chain that should not be tolerated, and a general lack of accountability. I also have no question that as we continue to emerge out of the pandemic there will be an advanced focus much more on the global revolution of sustainability, fair labor practices, plus a far-keener eye on the eco-systems in which the textile industry lives and breathes.

Kendall: There have been more heated debates on the future of China as an apparel sourcing base for US fashion companies, especially given the escalating U.S.-China trade war and the COVID-19. What is your view?

Jason: It should be noted that more than a billion dollars of trade in the textile sector in China was lost in export shipments to the USA during the first half of 2019 – primarily due to the trade war. The pandemic has since crippled exports of textile and apparel – in not just China – but also in every sourcing region on the planet. While many media outlets and others talk about the demise of China as a producer for textile and apparel that is just not the case. The Chinese have built an infrastructure, invested billions of dollars in the best technology, and have mastered the art of production over the last 3+ decades. We must not also forget that much of this infrastructure was built with trillions of dollars by the world’s leading brands, retailers, and governments. To bail on that would not be prudent. The Chinese are extremely adaptive and there is no question they have taken the time during the pandemic – and I should also note that they have emerged quicker than anyone else from the pandemic – to invest much more in technology, made-to-order, customization, and enhances on sustainable practices by utilizing more renewables.

Kendall: Many studies suggest that fashion companies continue to actively look for China’s alternatives. Do we have a “Next China” yet– Vietnam, Bangladesh, India, Ethiopia, or somewhere else?

Jason: No we do not have a next China yet. The production in many regions that have competent supply chains – like Vietnam – are full and at over-capacity. It should further be noted that a large portion in places like Vietnam are owned in partnerships thru the Chinese. Simply stated, many of the other regions such as Bangladesh, India, and the AGOA regions lack infrastructure and the decades of experience that the Chinese have.

Kendall: Some predict that near sourcing rather than global sourcing will become ever more popular as fashion companies are prioritizing speed to market and building a shorter supply chain. Why or why not do you think the shift to near sourcing or reshoring is happening?

Jason: This is correct. On-demand production, near-sourcing, and the evolution of digitization will of course lead to increased manufacturing domestically. Neither of these options are yet a solution for the high-volume production which is at the heart of the industry. I will agree that the continued emergence of micro-brands, and continually evolving shifts in consumer behavior which generally has resulted in ‘disloyalty’ to brands is another factor that makes on-shoring or near-shoring more attractive.

Kendall: Building a more sustainable and socially responsible textile and apparel supply chain is also growing in importance. From interacting with fashion brands and retailers, can you provide us with some updates in this area, such as companies’ best practices, issues they are working on, or the key challenges that remain?

Jason: The circularity of the industry encompassing the producer, the brand, logistics, and the consumer will continue to evolve in their social responsibilities and awareness of sustainable practices engaged in by the brand. There are great organizations out there like WRAP, TESTEX and Better Buying who are growing and have a much larger voice than what they have had in the past. Post-pandemic, I believe we will see social responsibility as one of the top priorities with so many millions of people displaces from COVID-19.

Kendall: For our students interested in pursuing a career in the textile and apparel industry, especially related to sourcing, do you have any suggestions?

Jason: The top suggestion I can offer is to pursue experience as you are actively engaged in your studies. One of the key elements I can advise of is to take the time and learn culture over language. Having a cultural understanding of the key regions where sourcing occurs will catapult your career and bring significant relationships to the table that you never thought you would have had before. Also, attend trade shows! Walking thru international apparel trade shows – like The Apparel Textile Sourcing – will help you immerse yourself with numerous different nationalities and personalities that you would otherwise never have the chance to meet. Jump on any opportunity you can to go abroad. Especially to regions in Asia and Latin America. Most importantly never forget that your credibility in life is everything and maintain the highest pedigree of integrity as possible.

-END-

COVID-19 and U.S. Apparel Imports (Updated: September 2020)

The latest statistics from the Office of Textiles and Apparel (OTEXA) show that the patterns of U.S. apparel imports continue to involve because of COVID-19 and the escalating US-China tensions. Meanwhile, there appeared to be more potent signs of gradual economic recovery in the U.S. driven by consumers’ robust demand. Specifically:

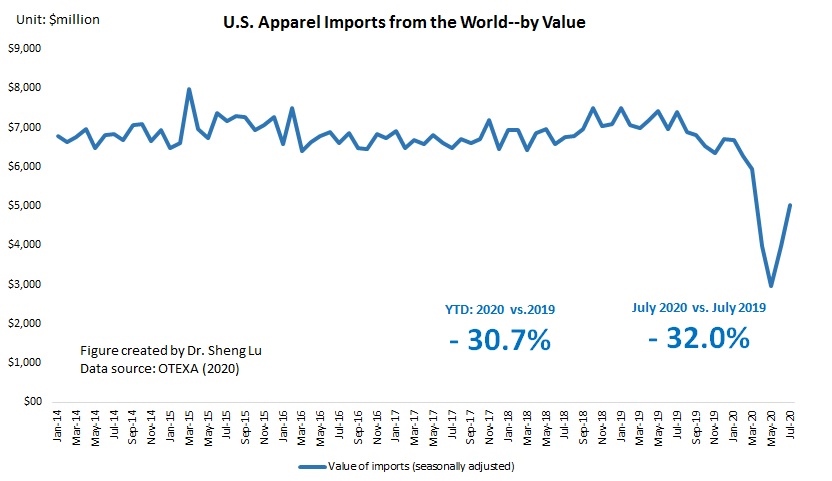

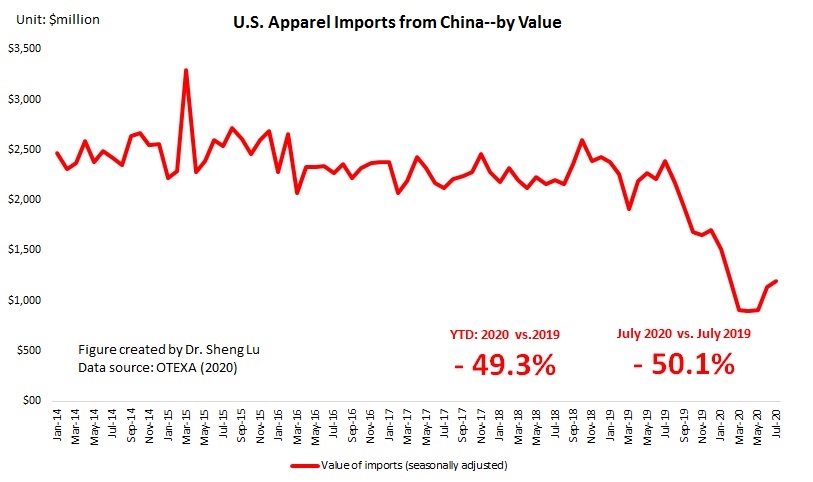

While the value of U.S. apparel imports decreased by 32.0% in July 2020 from a year ago, the speed of the decline has significantly slowed (was down 60% and 42.8% year over year in May and June 2020, respectively). This result echoes the trend of U.S. apparel retail sales (NAICS 448), which indicates a “V-shape” rebound since May 2020. As fashion brands and retailers typically build their inventory for holiday sales (such as back to school, Thanksgiving, and Christmas) from July to October, the upward trend of U.S. apparel imports could continue in the next two to three months.

Nevertheless, between January and July 2020, the value of U.S. apparel imports decreased by 30.7% year over year, which has been much worse than the performance during the 2008-2009 global financial crisis (down 11.8%).